In April of last year, archaeologists discovered a 4,500-year-old intact burial of a noblewoman at the ancient site of Apero in Caral, northcentral Peru. Her remains were found buried in the Huaca de los Idolos, a pyramidal structure made of overlapping platforms accessible via a central staircase built by the Norte Chico civilization, the oldest in the Americas which flourished in the area between the 4th and 2nd millennia B.C. She was carefully positioned in a crouch and wrapped in layers of textiles, a swath of cotton wrapped around her head, another cotton textile wrapped around body. Thus wrapped, her body was then bundled in a final layer, a reed fiber mat that was fastened closed with ropes. The mummy bundle was placed atop a stone basin containing plant matter offerings including a bowl of mate fragments, tubers and seeds. That was covered with a layers of ash and soil.

In April of last year, archaeologists discovered a 4,500-year-old intact burial of a noblewoman at the ancient site of Apero in Caral, northcentral Peru. Her remains were found buried in the Huaca de los Idolos, a pyramidal structure made of overlapping platforms accessible via a central staircase built by the Norte Chico civilization, the oldest in the Americas which flourished in the area between the 4th and 2nd millennia B.C. She was carefully positioned in a crouch and wrapped in layers of textiles, a swath of cotton wrapped around her head, another cotton textile wrapped around body. Thus wrapped, her body was then bundled in a final layer, a reed fiber mat that was fastened closed with ropes. The mummy bundle was placed atop a stone basin containing plant matter offerings including a bowl of mate fragments, tubers and seeds. That was covered with a layers of ash and soil.

Pinned to the cotton sheath that was wrapped around her body archaeologists found four “tupus,” brooches carved in the shape of animals: two birds with long tail feathers and chrysocolla minerals as eyes and two howler monkeys. They were placed on top of her shoulders and earned her her modern moniker. Underneath her where her tucked head almost touched her knees was a splendidly long necklace made of 460 white mollusk shell beads with a large pendant made from the shell of the spondylus mollusk. This was a rare and luxurious item that attests to her high position in Apero society, as do the tupu fasteners.

Pinned to the cotton sheath that was wrapped around her body archaeologists found four “tupus,” brooches carved in the shape of animals: two birds with long tail feathers and chrysocolla minerals as eyes and two howler monkeys. They were placed on top of her shoulders and earned her her modern moniker. Underneath her where her tucked head almost touched her knees was a splendidly long necklace made of 460 white mollusk shell beads with a large pendant made from the shell of the spondylus mollusk. This was a rare and luxurious item that attests to her high position in Apero society, as do the tupu fasteners.

Caral was a major urban center, long thought to be the most ancient city in the Americas and is certainly one of its most ancient. Covering more than 150 acres in area and inhabited by 3,000 people at its peak, it one of the largest Norte Chico sites known and its most thoroughly studied. No evidence has been found of defensive structures — no walls, no earthenware ditches, no battlements — nor have any weapons, mass graves or other indicators of warfare. Neither have archaeologists found remains suggesting the Norte Chico peoples practiced human sacrifice as later civilizations like the Incas would. About 14 miles from the main city of Caral, Apero was Caral’s harbour town and its primary source of fish.

Caral was a major urban center, long thought to be the most ancient city in the Americas and is certainly one of its most ancient. Covering more than 150 acres in area and inhabited by 3,000 people at its peak, it one of the largest Norte Chico sites known and its most thoroughly studied. No evidence has been found of defensive structures — no walls, no earthenware ditches, no battlements — nor have any weapons, mass graves or other indicators of warfare. Neither have archaeologists found remains suggesting the Norte Chico peoples practiced human sacrifice as later civilizations like the Incas would. About 14 miles from the main city of Caral, Apero was Caral’s harbour town and its primary source of fish.

Since the discovery of the mummy bundle, the Lady of the Four Brooches has been studied thoroughly. She was about five feet tall and right-handed. While her elaborate grave goods, burial method and location indicate she was a member of the elite of Apero, her bones show tell-tale signs of hard work during her lifetime, likely in agriculture or perhaps the

Since the discovery of the mummy bundle, the Lady of the Four Brooches has been studied thoroughly. She was about five feet tall and right-handed. While her elaborate grave goods, burial method and location indicate she was a member of the elite of Apero, her bones show tell-tale signs of hard work during her lifetime, likely in agriculture or perhaps the

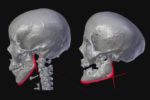

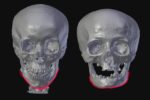

local mainstay, fishing. She also appeared to have suffered a serious fall shortly before her death, fracturing three bones. Her skull was flattened on top between the occipital and parietal regions, the result of intentional cranial deformation done when she was a baby before her skull bones had hardened, a widespread practice around the world, including in ancient Andean societies. She was between 40 and 50 years when she died.

local mainstay, fishing. She also appeared to have suffered a serious fall shortly before her death, fracturing three bones. Her skull was flattened on top between the occipital and parietal regions, the result of intentional cranial deformation done when she was a baby before her skull bones had hardened, a widespread practice around the world, including in ancient Andean societies. She was between 40 and 50 years when she died.

To bring her features back to life, an international team of archaeologists, scientists and artists collaborated on a facial reconstruction project, now complete. This was not a simple task. Her skull is 4,500 years old, after all, and has areas that are missing or severely stained by the decomposition process and the remains of the organic materials she was wrapped in. Brazilian 3D computer graphic artist Cicero Moraes was enlisted to turn that skull into a face. It took him two months to fill the gaps in the skull, replacing the missing eye socket by mirroring the complete one, comparing the Lady’s skull with that of a modern Peruvian woman of similar age and genetic ancestry and utilizing computer technology that simulates natural facial muscles using the skull as a foundation.

To bring her features back to life, an international team of archaeologists, scientists and artists collaborated on a facial reconstruction project, now complete. This was not a simple task. Her skull is 4,500 years old, after all, and has areas that are missing or severely stained by the decomposition process and the remains of the organic materials she was wrapped in. Brazilian 3D computer graphic artist Cicero Moraes was enlisted to turn that skull into a face. It took him two months to fill the gaps in the skull, replacing the missing eye socket by mirroring the complete one, comparing the Lady’s skull with that of a modern Peruvian woman of similar age and genetic ancestry and utilizing computer technology that simulates natural facial muscles using the skull as a foundation.

I don’t know why he would do such a thing in an ostensibly scientific research project, but he also softened the Lady of the Four Brooches’ features. He altered her markedly square, strong jawline he described as “masculine” so that her chin was more pointed giving her a softer more “feminine” appearance. (Women can’t have square jaws now? Somebody alert Paulina Porizkova to her lack of femininity stat!) He also hid her flat skull behind a headdress which was not among her

I don’t know why he would do such a thing in an ostensibly scientific research project, but he also softened the Lady of the Four Brooches’ features. He altered her markedly square, strong jawline he described as “masculine” so that her chin was more pointed giving her a softer more “feminine” appearance. (Women can’t have square jaws now? Somebody alert Paulina Porizkova to her lack of femininity stat!) He also hid her flat skull behind a headdress which was not among her  grave goods. Cranial modification was not something hidden by the societies that practiced it. That was the opposite of their intent. In fact, it was often a designator of societal status and considered beautiful. There is no justification I can think of for projecting one’s own highly subjective aesthetic choices using a modern

grave goods. Cranial modification was not something hidden by the societies that practiced it. That was the opposite of their intent. In fact, it was often a designator of societal status and considered beautiful. There is no justification I can think of for projecting one’s own highly subjective aesthetic choices using a modern  woman’s skull to distort the reconstruction. It should map directly to her real skull. What’s the point of using all those complex data tables and software to build up the soft tissues in an anatomically accurate manner if you’re going to gin up the bones they map to because you think a lady’s jawline isn’t dainty enough?

woman’s skull to distort the reconstruction. It should map directly to her real skull. What’s the point of using all those complex data tables and software to build up the soft tissues in an anatomically accurate manner if you’re going to gin up the bones they map to because you think a lady’s jawline isn’t dainty enough?

This bizarre choice is covered in the news stories and press materials entirely without comment as if it were totally ho-hum and not worth addressing. They just get right to the (admittedly compelling) finished digital reconstruction, unveiled Wednesday, October 11th, by the Ministry of Culture in Lima. I get it, because I’m always curious about facial reconstructions and have covered several, but I’ve never seen this kind of deliberate modification based on perceived chin cuteness and the artist’s preferred head shape. So I’d like to tell here she is, but the best I can do is say here are a few parts of her, including how her handsome adornments looked when worn.