Korean archaeologists have discovered the remains of an 8th century toilet in one of the palaces of the Silla monarchs in Gyeongju, a town of the southeast coast of Korea. The facilities were found by a team from the Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage in the Gyeongju East Palace, a smaller building that was part of the great Dong Palace complex of the ancient kingdom of Silla (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.). It too was a royal residence and therefore only the butts of the royal family squatted over that fine hole in the floor.

Korean archaeologists have discovered the remains of an 8th century toilet in one of the palaces of the Silla monarchs in Gyeongju, a town of the southeast coast of Korea. The facilities were found by a team from the Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage in the Gyeongju East Palace, a smaller building that was part of the great Dong Palace complex of the ancient kingdom of Silla (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.). It too was a royal residence and therefore only the butts of the royal family squatted over that fine hole in the floor.

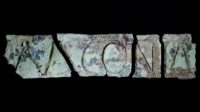

Made from granite, the toilet features an oval opening in the floor about five inches long with large rectangular stones on both sides of it. The flagstones were tilted upward slightly to ensure that one’s feet would not be getting invited to the evacuation party. The hole in the floor leads to a culvert where the waste was carried away.

Made from granite, the toilet features an oval opening in the floor about five inches long with large rectangular stones on both sides of it. The flagstones were tilted upward slightly to ensure that one’s feet would not be getting invited to the evacuation party. The hole in the floor leads to a culvert where the waste was carried away.

The Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage said Tuesday that excavation work at a site northeast of the Dong Palace in Gyeongju uncovered a stone flush toilet and draining system inside a stone structure.

It marked the first time for a bathroom structure, toilet and draining system to all be found at an ancient site in South Korea.

The institute explained that the oval-shaped flush toilet, made out of granite, has a drain and two rectangular slab stones on both sides apparently for users to plant their feet on when they are squatting.

An institute official said it appears that human excrement was flushed down the drain by pouring water into the toilet given that the bathroom had no water inflow equipment.

After use, the toilet would be “flushed” by dumping a lot of water into the hole. This is sufficient enough to get it props for being a flush toilet, but it’s a bit of a cheat though, because pouring a bucket of water into a hole cut into granite isn’t really the mechanism we think of as a “flush toilet.”

The rush of water ensured solid waste would move briskly through the culvert which was designed to use gravity as an aid, much like a Roman aqueduct. About 23 feet away from the toilet, the culvert is a foot and a half lower in grade than it is close to it. This incline kept the water (and the many gross things it carried) flowing.

The rush of water ensured solid waste would move briskly through the culvert which was designed to use gravity as an aid, much like a Roman aqueduct. About 23 feet away from the toilet, the culvert is a foot and a half lower in grade than it is close to it. This incline kept the water (and the many gross things it carried) flowing.

The depth of architectural and engineering analysis of waste management systems at the highest levels of social status and rank in 8th century Korea was possible at this site solely so much of the toilet and disposal structure has survived. This isn’t the first ancient toilet discovered in South Korea. (One at the Iksan royal palace dates to the 7th century; another at the Bulguksa Temple in Gyeongju from the 8th century.) Those aren’t complete, however. The palace’s draining toilet survives, but it has no foot slabs and no surviving drainage culvert. Same with the monastery.

The depth of architectural and engineering analysis of waste management systems at the highest levels of social status and rank in 8th century Korea was possible at this site solely so much of the toilet and disposal structure has survived. This isn’t the first ancient toilet discovered in South Korea. (One at the Iksan royal palace dates to the 7th century; another at the Bulguksa Temple in Gyeongju from the 8th century.) Those aren’t complete, however. The palace’s draining toilet survives, but it has no foot slabs and no surviving drainage culvert. Same with the monastery.

The materials are also very different. Granite was an expensive stone, difficult to quarry and carve. It does not appear in the earlier toilet at Iksan or in the much more modest facilities of the temple. This was one ultra fancy toilet. That’s one of the reasons archaeologists are convinced it was intended for use by members of the Silla royal family. They’re hoping to find some organic remains, microscopic intestinal parasites, perhaps, that will lend new insight into the diet, health of the highest echelon of Silla society.