Fragments of a 13th century Old French text of Arthurian legends have been found inside a series of later bound books in the Bristol Central Library. Seven handwritten manuscript fragments from the Vulgate Cycle, also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, were discovered by the University of Bristol’s Special Collections Librarian Michael Richardson while perusing a collection of the works of 15th century French scholar Jean Gerson.

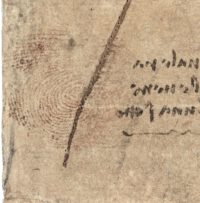

The four-volume edition of Gerson’s works was printed in Strasbourg between 1494 and 1502, but it seems they were not bound because the first binding appears to have been done in England in the early 16th century. That’s when the fragments of the Old French manuscript became integrated into the books. Parchment was expensive and bookbinders often reused old “waste materials” in their bindings instead of using clean sheets. There is evidence on the leaves that at this time they were pasted on the front and back boards of the books. When the books were rebound at a later date, the pasted fragments were unglued from the boards and used as flyleaves (those blank pages you still find today at the beginning and end of a volume).

Richardson recognized the names of key figures, most notably Merlin, from the Arthurian tales on the oft-recycled parchment pieces. He called in Dr. Leah Tether, an Arthurian expert from the University of Bristol’s English department to assess the significance of those names and manuscript fragments. She identified them as pieces of the Vulgate Cycle, a telling of the Arthur legend that predates all English-language versions and is thought to have been Sir Thomas Malory’s source for Le Morte D’Arthur. There are other surviving examples of the text, these fragments have intriguing differences in the narrative.

Richardson recognized the names of key figures, most notably Merlin, from the Arthurian tales on the oft-recycled parchment pieces. He called in Dr. Leah Tether, an Arthurian expert from the University of Bristol’s English department to assess the significance of those names and manuscript fragments. She identified them as pieces of the Vulgate Cycle, a telling of the Arthur legend that predates all English-language versions and is thought to have been Sir Thomas Malory’s source for Le Morte D’Arthur. There are other surviving examples of the text, these fragments have intriguing differences in the narrative.

The seven leaves represent a continuous sequence of the Estoire de Merlin narrative (though they are bound ‘out of chronological order’ in their current form) – specifically in a section known as the ‘Suite Vulgate de Merlin’ (Vulgate Continuation of Merlin).

Events begin with Arthur, Merlin, Gawain and assorted other knights, including King Ban and King Bohors preparing for battle at Trebes against King Claudas and his followers.

Merlin has been strategising the best plan of attack. There follows a long description of the battle. At one point, Arthur’s forces look beleaguered but a speech from Merlin urging them to avoid cowardice leads them to fight again, and Merlin leads the charge using Sir Kay’s special dragon standard that Merlin had gifted to Arthur, which breathes real fire.

In the end, Arthur’s forces are triumphant. Kings Arthur, Ban and Bohors, and the other knights, are accommodated in the Castle of Trebes.

That night Ban and his wife, Queen Elaine, conceive a child. Elaine then has a strange dream about a lion and a leopard, the latter of which seems to prefigure Elaine’s yet-to-be-born son. Ban also has a terrifying dream in which he hears a voice. He wakes up and goes to church.

We are told that during Arthur’s stay in the kingdom of Benoic for the next month, Ban and Bohors are able to continue to fight and defeat Claudas, but after Arthur leaves to look after matters in his own lands, Claudas is once again triumphant.

The narrative then moves to Merlin’s partial explanation of the dreams of Ban and Elaine. Afterwards, Merlin meets Viviane who wishes to know how to put people to sleep (she wishes to do this to her parents). Merlin stays with Viviane for a week, apparently falling in love with her, but resists sleeping with her. Merlin then returns to Benoic to rejoin Arthur and his companions.

In the newly discovered fragments, there tend to be longer, more detailed descriptions of the actions of various characters in certain sections – particularly in relation to battle action.

Where Merlin gives instructions for who will lead each of the four divisions of Arthur’s forces, the characters responsible for each division are different from the version of the narrative we know.

Sometimes only small details are changed – for example, King Claudas is wounded through the thighs in the known version, where in the fragments the nature of the wound is left unsaid, which may lead to different interpretations of the text owing to thigh wounds often being used as metaphors for impotence or castration.

The damage to the fragments from their use in two different bindings will make it challenging to fully decipher the text. Researchers will use infrared imaging, if necessary, to read through the damage and publish a full transcript of the exciting new finds.