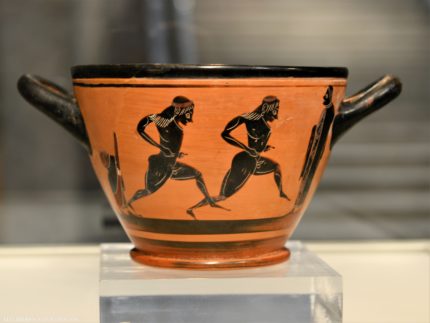

An ancient drinking cup given to the first marathon winner in Olympic history has been returned to Greece from the University of Münster in Germany. The 6th century B.C. black-figure skyphos depicting two and two Hellanodikai (judges at the ancient Olympic games) was given to Spyridon “Spyros” Louis after he won the 25-mile race from Marathon to Athens at the 1896 Olympic Games.

Greek officials announced that the skyphos would be given a place of honour in the Museum of the History of the Ancient Olympic Games (formerly the Archaeological Museum) in Olympia. “Its future place of honour is where the skyphos was naturally meant to be. I am very happy that the University of Münster could help make this possible,” underlined Münster University’s Rector Prof. Johannes Wessels.

The vessel was part of the Peek Antiquities Collection acquired by the university in 1986. The collection of 70 ancient Greek ceramic vessels was assembled by German epigraphist Werner Peek who lived in Athens from 1930 to 1937. How Peek came across Spyros Louis’ skyphos is unknown.

Born to a poor family in the village of Marousi outside of Athens, Spyros Louis was a 23-year- old water carrier when he qualified as a runner in the marathon. This was a new event, never held in the ancient games but conceived to connect the modern games to the traditions of antiquity by making a foot race out of the story of the messenger Pheidippides who heroically ran from Marathon to Athens to deliver the news of the Athenian victory against the Persians and dropped dead upon arrival. There was an enormous amount of excitement over the marathon, and when a Greek peasant defeated some of the world’s best trained runners in so storied a race, Spyros Louis became a national hero.

Spyros died in 1940. The official prizes he had received for winning the first marathon — including the silver medal (until 1904, first place winners received silver medals and second place bronze) and the silver Bréal Cup — passed to his children. His grandson sold the Bréal Cup at auction in 2012 where it set a new record for Olympic memorabilia.

He received a plethora of other gifts and prizes from ecstatic fans in the wake of his win, everything from gold watches to two coffees a day at a local bar and free haircuts for life. The skyphos was a gift from numismatist Ioannis Lambros who had a private collection of artifacts. He was so inspired by the very idea of the marathon that before the games he wrote to Crown Prince Constantine:

“Your Royal Highness, The distinction, which the Marathon Race is called upon to give to the Olympic Games, joined to the ancient reminiscences, which this difficult race is sure to awake, have suggested to me the idea of offering as a most appropriate prize to the winner, who will be worthy of so much glory, an ancient vase, which I have in my collection; on it are represented a dolichodrome under the guidance of Hellanodices. May I hope that Your Royal Highness will allow me to add this prize to the Silver Cup, which Professor Bréal has donated. Antiquity seems in this way to contribute to celebrate the victory of the winner of the Marathon Race.”

Articles about the vessel in the press at the time described it as having been found in a grave in Thebes believed to have belonged to a victorious runner in one of the ancient games. An 1896 issue of Scribers Magazine claimed Spyros had given the skyphos to the National Archeological Museum, but there were no records of such a donation or even a loan, and the vessel was very famous, even appearing on a Greek stamp celebrating the Pre-Olympic Games in 1967.

It was rediscovered in 2014 by Dr. Georgos Kavvadias of the Greek National Museum who recognized it from a picture in a University of Münster monograph. He worked with the university’s researchers to confirm its identity and, once confirmed, to facilitate its repatriation.

“The skyphos has a highly symbolic significance for Greece, the birthplace of the Olympic Games. We naturally wanted to give it back,” explained the director of the Archaeological Museum of the University of Münster, Prof. Dr Achim Lichtenberger, who also participated in the ceremony. “Morally speaking and with respect to sports history, this piece belongs in Greece,” added museum curator Dr Helge Nieswandt.