The ancient board game of senet dates back at least to Egypt’s First Dynasty (ca. 3000 B.C.) and continued to be popular with people at all levels of society through the Greco-Roman Period. Boards — formal ones and impromptu versions in graffiti and painted or scratched onto ostraca (pottery fragments) — game pieces, surviving texts and depictions on tomb walls make it one of the best documented games in history.

Even so, there is still much we don’t know about senet and how it was played, and its extraordinary longevity makes it a unique example of how games evolve over time. A new study of a previously unpublished senet board in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose, California, has found it to be an important transitional piece in the development of the game.

Even so, there is still much we don’t know about senet and how it was played, and its extraordinary longevity makes it a unique example of how games evolve over time. A new study of a previously unpublished senet board in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose, California, has found it to be an important transitional piece in the development of the game.

At its core, senet was a backgammon-like game in which two players vied to move their five pawns through the rows in a serpentine pattern to the last square. They used throw sticks to determine how to move the pawns. Depending how many of the sticks landed on the flat side, players moved different numbers of spaces. Pieces could pass each other, get knocked out, blocked, go backwards as well as forwards. The first player to get all the tokens off the board from square 30 won.

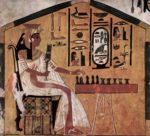

Four (five in some variations of the grid) of the squares had symbols on the squares marking those cells as having special functions. They were called  houses and could trap a piece, send it back, give the player a second turn, etc. Those symbols went from game mechanisms to religious allegories in the New Kingdom. Depictions of the game on tomb walls, which in the Old Kingdom featured people playing against each other, now featured the deceased playing an invisible opponent. Texts from the period indicate the game connected the souls of the dead and the living, and that the houses represented obstacles and steps encountered by the soul on the way to the afterlife.

houses and could trap a piece, send it back, give the player a second turn, etc. Those symbols went from game mechanisms to religious allegories in the New Kingdom. Depictions of the game on tomb walls, which in the Old Kingdom featured people playing against each other, now featured the deceased playing an invisible opponent. Texts from the period indicate the game connected the souls of the dead and the living, and that the houses represented obstacles and steps encountered by the soul on the way to the afterlife.

The Rosicrucian board is actually a table. Carved out of a single piece of cedar, it features a playing surface, a panel running along the rear length and two rectangular legs at each end crossing the full width of the board. It is the only senet table ever discovered. Although there are depictions of senet tables in Egyptian art, all other senet boards that have been found are boxes, slabs and graffiti.

The Rosicrucian board is actually a table. Carved out of a single piece of cedar, it features a playing surface, a panel running along the rear length and two rectangular legs at each end crossing the full width of the board. It is the only senet table ever discovered. Although there are depictions of senet tables in Egyptian art, all other senet boards that have been found are boxes, slabs and graffiti.

The surface is worn, but the typical senet grid pattern — 30 squares in three rows of 10 — is incised into the tabletop. Four of the squares, numbers 26, 27, 28 and 29, contain symbols written in hieroglyphic cursive: nfr (good), a sort of rustic version of the Ankh, mw (water) drawn as three parallel lines, three seated men and two seated men.

In their upright orientation, the hieroglyphs are positioned at the top left of the board, a variant most often found in the Middle Kingdom/Second Intermediate Period, instead of the bottom right. The seven senet boards that have been discovered with this orientation date to the 12th – 17th Dynasties, but they do not have the same symbols. The writing on the Rosicrucian senet is instead typical of the 18th Dynasty.

The comparative material discussed in the foregoing section suggests that the senet board in the Rosicrucian Museum demonstrates a transitional stage in the pattern of decoration between the Middle Kingdom/Second Intermediate Period and the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The orientation of the board, with the marked squares at the top left, points to an early date. The latest board with the same orientation as the Rosicrucian senet is drawn in ink on the back of a schoolboy’s writing tablet (the ‘Carnarvon Tablet’), now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (JdE 41.790). It was found by Howard Carter in Asasif Tomb 9, and dates to the Seventeenth Dynasty. All other previously published senet boards dating later than this board—for which orientation can be determined—show the opposite configuration, with squares 26 to 29 at the lower right. […]

Considering the morphology of the Rosicrucian senet game, the date range during which people were making similar choices in the design of game boards extends from the Twelfth Dynasty (based on orientation) to the Nineteenth Dynasty (because it is a game box). The end points of this range can be narrowed down further based on the style of the markings in squares 26 to 29. Since the markings do not contain the superfluous ones seen in the Middle Kingdom boards, that period can be eliminated as a possible date. Furthermore, the progression of nfr, mw, three seated men, and two seated men only has parallels in the early Eighteenth Dynasty, specifically the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

This leaves a gap, however, between the last known example of a game with the top left orientation of squares 26 to 29 (Seventeenth Dynasty), and the appearance of this particular style of marking (Hatshepsut), of roughly 70 years. There are currently no senet boards that can be attributed to the period from the reign of Ahmose I to that of Thutmose II. Thus, the evolution of senet boards from the earlier games of the Middle Kingdom—with their simple decoration and top left placement of the marked squares—to that of the New Kingdom—with elaborated decoration and lower right placement of marked squares—is poorly understood. We know that at least during the Seventeenth Dynasty, game boxes and boards with the top left orientation coexisted, as evidenced by the game from the Tomb of Hornakht at Dra Abu el-Naga and the Carnarvon Tablet. There is, however, no evidence for the elaborated decoration seen on the Rosicrucian board during the Second Intermediate Period. These same two boards are the only ones marked from that period, and the Hornakht box only contains m in square 27, and the Carnarvon Tablet has nfr, X, three, two.

It would seem prudent to propose then, that the game box in the Rosicrucian Museum represents a transitional form between the top left oriented schoolboy’s tablet and the game box with nearly identical markings from the tomb of Hatshepsut. No other games can be securely dated to the intervening period either through archaeological context or by style alone, so this game is a likely candidate to fill that stylistic gap.

There is almost no information about the Rosicrucian board’s history. It entered the museum’s collection in 1947. The previous owner was Lord William-Tyssen Amherst, First Baron of Hackney, who acquired a large collection of antiquities in the late 19th century. Where it came from or where he got it is unknown, other than that he died in 1906 so he had to have purchased it before then. Without its original archaeological context, the only possible way to confirm its age is radiocarbon dating.