A high-status Iron Age chariot burial has been discovered in the town of Corinaldo, near the Adriatic coast of Le Marche in central Italy. All human remains had decayed, but a profusion of exceptional grave goods date the burial the Orientalising period, between the late 8th century and early 6th century B.C.

A high-status Iron Age chariot burial has been discovered in the town of Corinaldo, near the Adriatic coast of Le Marche in central Italy. All human remains had decayed, but a profusion of exceptional grave goods date the burial the Orientalising period, between the late 8th century and early 6th century B.C.

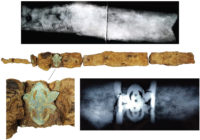

The site, slated for construction of a new sports complex, was identified as archaeologically significant first by aerial photography, then with non-invasive geomagnetic and electrical resistance surveys that gave the excavation team key information on where to open trial trenches. They unearthed a large funerary area (half a hectare, ca. 54,000 square feet) with  three large ring ditches. Roman tombs were also found there, but ring ditches long pre-dated them. In the central ring ditch was a pit surrounded by a circular moat almost 100 feet wide, a perimeter that may indicate there was once a tumulus atop the burial. The grave itself is 10.5 by 9 feet and contains a mass of objects, among them a bronze helmet, iron skewers, bronze vessels, more than a hundred ceramic vessels and an iron-wheeled chariot.

three large ring ditches. Roman tombs were also found there, but ring ditches long pre-dated them. In the central ring ditch was a pit surrounded by a circular moat almost 100 feet wide, a perimeter that may indicate there was once a tumulus atop the burial. The grave itself is 10.5 by 9 feet and contains a mass of objects, among them a bronze helmet, iron skewers, bronze vessels, more than a hundred ceramic vessels and an iron-wheeled chariot.

The wealth of grave goods, the chariot and the likelihood that the burial was once covered by a mound point to the deceased having been a member of the aristocratic elite of the Piceni, an Italic people who inhabited central  and northeast Italy between the Appenines and the Adriatic before the rise of Rome. Little is known of the Piceni Culture in northern Le Marche, so the richness of this discovery will shed new light on the people who dominated the prehistory of the area. The pottery alone indicates active trade between the Piceni of this area and what is now northern Apulia (the heel of Italy’s boot).

and northeast Italy between the Appenines and the Adriatic before the rise of Rome. Little is known of the Piceni Culture in northern Le Marche, so the richness of this discovery will shed new light on the people who dominated the prehistory of the area. The pottery alone indicates active trade between the Piceni of this area and what is now northern Apulia (the heel of Italy’s boot).

Ongoing investigations at the site and analyses of the archaeometric, environmental and archaeozoological material will strengthen our understanding of the site’s importance in terms of its chronology, ‘structural’ characteristics and ritual or cultural aspects. They will also reveal contemporaneous relationships within the broader populated landscape, promising new insights into the role of the Nevola Valley in the Iron Age settlement dynamics of the Marche region. Inevitably, questions remain about certain aspects of the tomb’s morphology, including the possible existence of a covering mound as opposed to a circular ditch and bank, perhaps supplemented by standing stones or timber uprights.

Still under debate, too, is the unknown position of the body within the royal tomb. Comparison with similar aristocratic interments farther to the south suggest differing possibilities, perhaps with the body placed at a higher level immediately above the grave goods, or within a shallow pit nearer the centre of the ring-ditch; the royal corredo (funerary assemblage) at Corinaldo did not occupy that central position or yield any skeletal material. In either case, it seems probable that the body was placed somewhere at or near the ancient ground surface. If so, it would have had little chance of surviving the centuries of subsequent ploughing that have removed all traces of any above ground mound.