One of 300 skeletons discovered on the ancient beach at Herculaneum in the 1980s has been identified as a senior officer in the rescue mission launched by Pliny the Elder after the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Skeleton 26, an adult man around 40 years old when the volcano claimed his life, was initially identified as a soldier based on his muscular build and uniform elements, but a recent analysis of his gear indicates that he was far more than a simple soldier, a high-ranking officer certainly, likely a naval officer deployed to help evacuate the residents of Herculaneum.

One of 300 skeletons discovered on the ancient beach at Herculaneum in the 1980s has been identified as a senior officer in the rescue mission launched by Pliny the Elder after the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Skeleton 26, an adult man around 40 years old when the volcano claimed his life, was initially identified as a soldier based on his muscular build and uniform elements, but a recent analysis of his gear indicates that he was far more than a simple soldier, a high-ranking officer certainly, likely a naval officer deployed to help evacuate the residents of Herculaneum.

The skeletal remains of people seeking shelter in the boat sheds on Herculaneum’s beach first emerged in 1982. They were the first human remains found in the town which was previously believed to have been successfully evacuated before the eruption buried the city in 60 feet of hardening volcanic rock. The 300 people fled to the beach in hope of being rescued by ship. They took shelter inside roofed archways that under non-apocalyptic conditions were used to store gear and nets from fishing boats.

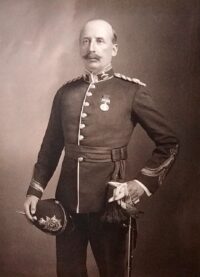

Skeleton 26 was found face-down in the sand, thrown to the ground by the force of the pyroclastic flow that hit the city going 60 miles an hour and killed everyone in the sheds. He wore a leather belt decorated with silver and gold foil from which hung a gladius (short sword) with an ivory grip. On the other side of him was a pugio (dagger) also highly decorated. Next to the body was a group of coins — 12 silver denarii and two gold coins — that add up to the monthly salary of a Praetorian Guard in the first century. On his back was a rectangular backpack holding a set of tools. A few feet away were the remains of a military boat, the rescue ship the evacuees had waited for only to be killed before they could step foot on it.

Skeleton 26 was found face-down in the sand, thrown to the ground by the force of the pyroclastic flow that hit the city going 60 miles an hour and killed everyone in the sheds. He wore a leather belt decorated with silver and gold foil from which hung a gladius (short sword) with an ivory grip. On the other side of him was a pugio (dagger) also highly decorated. Next to the body was a group of coins — 12 silver denarii and two gold coins — that add up to the monthly salary of a Praetorian Guard in the first century. On his back was a rectangular backpack holding a set of tools. A few feet away were the remains of a military boat, the rescue ship the evacuees had waited for only to be killed before they could step foot on it.

Herculaneum archaeologists at first focused on studying the recovered bones, but recently researchers returned to backpack, belt and weapons for an in-depth analysis. The study revealed that the belt’s gold and silver foil decorations depicted a lion and a cherub. The scabbard of the gladius was adorned with an oval shield. The work tools in the backpack were typical of the faber navalis, a naval engineer who specialized in carpentry.

Recently another team of researchers performed a DNA test on the skull of another skeleton, found more than a hundred years ago on a beach near Pompeii, thought to be that of Pliny the Elder. Like the skeleton in Herculaneum, it was wearing a heavily ornamented sword and was draped with golden necklaces and bracelets.

Pliny the Younger described his uncle’s fatal final mission to save the inhabitants of the Gulf of Naples in a letter to the historian Tacitus, which also contains the first description of what volcanologists would later dub a Plinian eruption.

My uncle was stationed at Misenum, where he was in active command of the fleet, with full powers. On the 24th of August [date is a centuries-old transcription/translation error; eruption was in October], about the seventh hour, my mother drew his attention to the fact that a cloud of unusual size and shape had made its appearance. He had been out in the sun, followed by a cold bath, and after a light meal he was lying down and reading. Yet he called for his sandals, and climbed up to a spot from which he could command a good view of the curious phenomenon. Those who were looking at the cloud from some distance could not make out from which mountain it was rising – it was afterwards discovered to have been Mount Vesuvius – but in likeness and form it more closely resembled a pine tree than anything else, for what corresponded to the trunk was of great length and height, and then spread out into a number of branches, the reason being, I imagine, that while the vapour was fresh, the cloud was borne upwards, but when the vapour became wasted, it lost its motion, or even became dissipated by its own weight, and spread out laterally. At times it looked white, and at other times dirty and spotted, according to the quantity of earth and cinders that were shot up.

To a man of my uncle’s learning, the phenomenon appeared one of great importance, which deserved a closer study. He ordered a Liburnian galley to be got ready, and offered to take me with him, if I desired to accompany him, but I replied that I preferred to go on with my studies, and it so happened that he had assigned me some writing to do. He was just leaving the house when he received a written message from Rectina, the wife of Tascus, who was terrified at the peril threatening her – for her villa lay just beneath the mountain, and there were no means of escape save by shipboard – begging him to save her from her perilous position. So he changed his plans, and carried out with the greatest fortitude the task, which he had started as a scholarly inquiry.

He had the galleys launched and went on board himself, in the hope of succoring, not only Rectina, but many others, for there were a number of people living along the shore owing to its delightful situation. He hastened, therefore, towards the place whence others were fleeing, and steering a direct course, kept the helm straight for the point of danger, so utterly devoid of fear that every movement of the looming portent and every change in its appearance he described and had noted down by his secretary, as soon as his eyes detected it. Already ashes were beginning to fall upon the ships, hotter and in thicker showers as they approached more nearly, with pumice-stones and black flints, charred and cracked by the heat of the flames, while their way was barred by the sudden shoaling of the sea bottom and the litter of the mountain on the shore. He hesitated for a moment whether to turn back, and then, when the helmsman warned him to do so, he exclaimed, “Fortune favours the bold….”

Bold he most certainly was — he took a leisurely bath, had a dinner, took a nap, finally made his way to the shore with a pillow tied to his head to protect against the pumice fall — but alas not fortunate. Pliny the Elder died on the beach, suffocated by the volcanic gases that suffused the air.

A new excavation of the ancient beach begins this month. Archaeologists are also working on extracting DNA from the skeletons of Herculaneum.

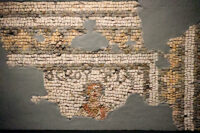

The mosaic panels unearthed at the ancient site of Antioch in the 1930s only to be reburied under the east lawn of the Museum of Fine Art in St. Petersburg, Florida, in the 1980s, have gone on display in a new exhibition at the museum.

The mosaic panels unearthed at the ancient site of Antioch in the 1930s only to be reburied under the east lawn of the Museum of Fine Art in St. Petersburg, Florida, in the 1980s, have gone on display in a new exhibition at the museum. The neglected mosaic collection got some much-needed attention with the appointment of new executive director Kristen Shepherd in 2017. She found the one in storage, had the ones under the lawn excavated and detached the one that had been embedded in the fountain. Three years of cleaning and conservation later, the five mosaic panels (plus one previously unrecorded fragment found in the east lawn excavation) have gone on display in Antioch Reclaimed: Ancient Mosaics at the MFA, open through August 22nd.

The neglected mosaic collection got some much-needed attention with the appointment of new executive director Kristen Shepherd in 2017. She found the one in storage, had the ones under the lawn excavated and detached the one that had been embedded in the fountain. Three years of cleaning and conservation later, the five mosaic panels (plus one previously unrecorded fragment found in the east lawn excavation) have gone on display in Antioch Reclaimed: Ancient Mosaics at the MFA, open through August 22nd.“Our acquisition of these mosaics from Princeton a year before the museum opened represents a message that the museum would be an encyclopedic art museum and the founders had that in mind. They were the first shipments of art at our loading dock, so it was a big deal,” says Michael Bennett, Ph.D., the MFA’s curator of Early Western Art. “With Princeton’s full collaboration, we’re telling the story of their 1930s excavation and Antioch. We’re including a documentary film made by the archeologists during that excavation that’s never been seen by the general public. Princeton has never loaned any of this archival material before, so this is a world premiere.”