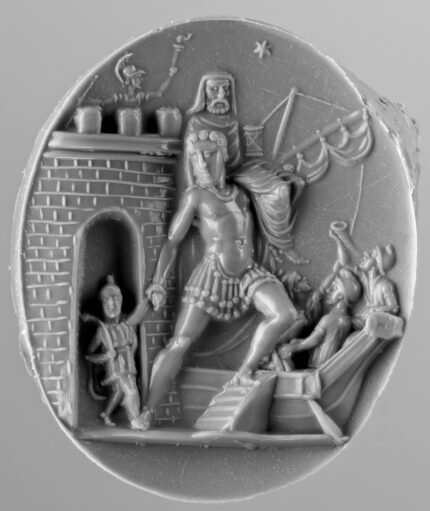

The motif of Aeneas fleeing Troy was popular in Greek decorative arts, adorning vases as early as the 6th century B.C., and it took on added significance in Italy because legend had it that Aeneas settled in Latium, married a nice Latin girl and became the forefather of the dynasty culminating in Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome. The scene from Book II of the Aeneid (and from a much earlier Greek account of the sack of Troy now lost) was frequently depicted on Roman gemstones and coins. The Getty Museum acquired one of those intaglio stones in 2019 and it is without question the most detailed, most finely rendered, most three-dimensional example known.

Made from an oval cornelian less than an inch long, the depth of field carved out of this small piece of hard stone with tiny cutting wheels, sharp tools and abrasives is extraordinary. It was made in Italy, possibly Rome itself, around 20 B.C. during the reign of Augustus, adopted son of Julius Caesar whose family traced their unbroken ancestral line directly back to Aeneas and therefore his mom Venus. Virgil dedicated The Aeneid to Augustus and makes explicit reference to the ancestral connection linking him to the Trojan hero.

Made from an oval cornelian less than an inch long, the depth of field carved out of this small piece of hard stone with tiny cutting wheels, sharp tools and abrasives is extraordinary. It was made in Italy, possibly Rome itself, around 20 B.C. during the reign of Augustus, adopted son of Julius Caesar whose family traced their unbroken ancestral line directly back to Aeneas and therefore his mom Venus. Virgil dedicated The Aeneid to Augustus and makes explicit reference to the ancestral connection linking him to the Trojan hero.

[Brief explanatory digression: according to Getty curator of antiquities Kenneth Lapatin, the stone is cornelian, not carnelian which is the standard term. Apparently “carnelian” is a medieval misinterpretation of the etymology of the name. Medieval scholars believed the name of the stone was derived from the Latin “carne” (flesh) when it actually was named after the Cornus mas, aka the Cornelian cherry, which produces a deep red fruit similar to the color of the stone.]

In the foreground is Aeneas wearing a cuirass as his sole armor and pteruges, the skirt of leather strips worn by Greek and Roman soldiers. He carries his artfully draped and bemantled father Anchises on his left shoulder. Anchises carries a cylindrical contained with an X-shaped moulding, the reliquary containing the household gods and sacred objects  Aeneas told him to schlep because the hero had the blood of battle of his hands. Aeneas holds the hand of his little son Ascanius/Iulus, leading him through the gates of Troy. The boy is elaborately garbed in chiton, a cloak and a Phrygian cap with a pedum (a curved stick used as a throwing weapon by hunters) over his left shoulder. The walls of the city, ashlar blocks in clear relief, still stand, but the Greek soldier in a crested helmet holding a torch on the battlements portends Troy’s destruction by fire. Aeneas climbs the ladder to the ship that will take them to safety. It is manned by three men in Phrygian caps, one at the rudder, one sounding a trumpet, one unfurling the sail. Above them all is a single star, the “sacred star” or comet sent by Jupiter as a sign to Anchises that he should flee with his son instead of sticking it out as Troy burns down around him.

Aeneas told him to schlep because the hero had the blood of battle of his hands. Aeneas holds the hand of his little son Ascanius/Iulus, leading him through the gates of Troy. The boy is elaborately garbed in chiton, a cloak and a Phrygian cap with a pedum (a curved stick used as a throwing weapon by hunters) over his left shoulder. The walls of the city, ashlar blocks in clear relief, still stand, but the Greek soldier in a crested helmet holding a torch on the battlements portends Troy’s destruction by fire. Aeneas climbs the ladder to the ship that will take them to safety. It is manned by three men in Phrygian caps, one at the rudder, one sounding a trumpet, one unfurling the sail. Above them all is a single star, the “sacred star” or comet sent by Jupiter as a sign to Anchises that he should flee with his son instead of sticking it out as Troy burns down around him.

Like many intaglio gems, this was likely mounted into a signet ring and impressed into wax as an identifier. As much of a masterpiece as the stone is on its own, the impression of it conveys its extraordinary craftsmanship even more clearly. I mean look at this:

It’s nuts that that kind of granular detail is even possible on a stone 7/8 × 11/16 × 1/4 inches in dimension.

The Aeneas intaglio is now on display at the Getty Villa in the Roman Treasury room.