A group of 51 painted glazed bricks from the little-known Mannaean civilization that were looted from ancient site of Qalaichi in northwestern Iran will go on display for the first time in Bukan City, five miles from where they were plundered four decades ago.

A group of 51 painted glazed bricks from the little-known Mannaean civilization that were looted from ancient site of Qalaichi in northwestern Iran will go on display for the first time in Bukan City, five miles from where they were plundered four decades ago.

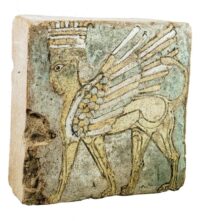

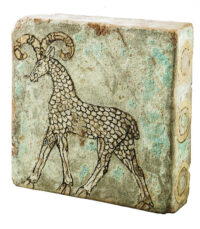

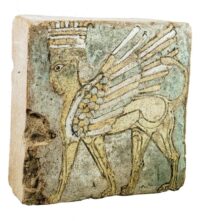

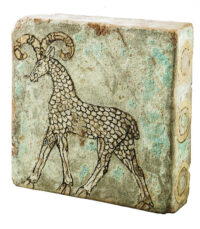

The bricks were manufactured in the 8th or 7th century B.C. and are each about one square foot in dimension. They feature a variety of decorative motifs, from simple monochrome paint, floral and geometric designs to depictions of sphinxes, antelopes, birds of prey, rams and lamassus (winged bulls with human heads).

They were illegally exported to Switzerland before 1991 when an Iranian dealer attempted to sell them to the British Museum. They were too obviously looted even for the BM, and the dealer was unable to unload them to anyone else either. The bricks stayed in a warehouse in Chiasso, just over the Swiss-Italian border, until 2008 when the contents of the facility were seized due to nonpayment of the storage bill. The Swiss authorities confiscated the bricks and Tehran’s National Museum formally requested their return. Iran’s Cultural Heritage Ministry subsequently filed suit and it has taken more than a decade for it to finally come to fruition.

They were illegally exported to Switzerland before 1991 when an Iranian dealer attempted to sell them to the British Museum. They were too obviously looted even for the BM, and the dealer was unable to unload them to anyone else either. The bricks stayed in a warehouse in Chiasso, just over the Swiss-Italian border, until 2008 when the contents of the facility were seized due to nonpayment of the storage bill. The Swiss authorities confiscated the bricks and Tehran’s National Museum formally requested their return. Iran’s Cultural Heritage Ministry subsequently filed suit and it has taken more than a decade for it to finally come to fruition.

The Mannaeans occupied large parts of what are now the Iranian provinces of Kurdistan, East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan between around the 10th and 7th centuries B.C. The small polity was neighbored by the powerful empires of Assyria and Urartu and would ultimately be fragmented in the conflicts between the two great powers. Qalaichi was occupied between 9th and 7th centuries. It was abandoned after the Mannaean kingdom was conquered by the Medes in 615 B.C. and disappeared as a culturally distinct group.

It seemed to disappear from the archaeological record too. The first breakthrough took place in 1936 with the discovery of the Mannaean site at Ziwiye in Kurdistan. The Mannaean settlement at Qalaichi first emerged by accident in the 1970s when a farmer ploughing his fields churned up a decorated brick. Word got out and the looters descended like locusts with bulldozers, taking advantage of the upheaval of the Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq War to viciously plunder the site from 1979 until archaeologists were finally sent in 1985 on an emergency salvage mission.

It seemed to disappear from the archaeological record too. The first breakthrough took place in 1936 with the discovery of the Mannaean site at Ziwiye in Kurdistan. The Mannaean settlement at Qalaichi first emerged by accident in the 1970s when a farmer ploughing his fields churned up a decorated brick. Word got out and the looters descended like locusts with bulldozers, taking advantage of the upheaval of the Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq War to viciously plunder the site from 1979 until archaeologists were finally sent in 1985 on an emergency salvage mission.

The archaeological team unearthed numerous glazed bricks and a broken stele with a 13-line inscription in Aramaic that is the tail end of a treaty. It’s mostly a very detailed curse against anyone who would dare remove the stele (eg,”May seven cows suckle a single calf, but let it not be sated”), but it conveys that of the two parties to the treaty, one, the Mannaean side, supported by Haldi, god of war and patron deity of the Urartian royal dynasty, and an unknown second party, supported by Hadad, god of storm. It also states the Mannaean name for Qalaichi: Z’TR.

Unfortunately that one dig would be all the professional archaeology the site would get for another 15 years. The war made the area too hot and the looters came back to violate Qalaichi’s patrimony uninterrupted until a second official excavation took place in 1999. The filthy products of all this devastation were sold on the international antiquities market with plenty of takers among private collectors and museums. Mannaean material remains are exceedingly rare and every piece counts in shedding light on its culture. The homecoming of 51 of the bricks stolen during the long periods of destructive looting thus takes on even more importance.

Unfortunately that one dig would be all the professional archaeology the site would get for another 15 years. The war made the area too hot and the looters came back to violate Qalaichi’s patrimony uninterrupted until a second official excavation took place in 1999. The filthy products of all this devastation were sold on the international antiquities market with plenty of takers among private collectors and museums. Mannaean material remains are exceedingly rare and every piece counts in shedding light on its culture. The homecoming of 51 of the bricks stolen during the long periods of destructive looting thus takes on even more importance.

The Repatriated Boukan Glazed Brick Collection from Switzerland exhibition will open at the Haghighi Museum in Boukan and then move to the Iran National Museum in Tehran as soon as COVID allows.

The grave of a man buried with four horses, cattle, sheep and his dog has been discovered in the ancient fortress site of Çavuştepe near Van in eastern Turkey. The burial is about 2,800 years old and likely belonged to a member of the ruling and/or military elite of the Kingdom of Urartu. This is the first instance of an individual buried with animals on the Urartian archaeological record.

The grave of a man buried with four horses, cattle, sheep and his dog has been discovered in the ancient fortress site of Çavuştepe near Van in eastern Turkey. The burial is about 2,800 years old and likely belonged to a member of the ruling and/or military elite of the Kingdom of Urartu. This is the first instance of an individual buried with animals on the Urartian archaeological record.“This place has always brought firsts to us about the Urartian burial tradition. Today, we have encountered one of those firsts. In the studies we carried out with our expert team, we found an in-situ [in its original place] tomb. We saw a human being buried with his animals. Pieces of pottery were found right next to it. Here we also found an oil lamp with a bulb that we have never seen before. It also gives important tips about lighting.”