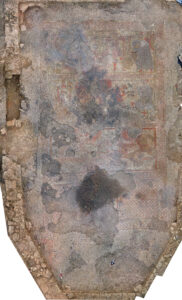

An exceptional mosaic depicting scenes from the clash between Achilles and Hector at the end of the Trojan War has been unearthed at Rutland in the East Midlands. It is one of only a handful of mosaics with this motif known to survive and the rest are on continental Europe. This is the first mosaic depicting Achilles and Hector ever discovered in the UK.

An exceptional mosaic depicting scenes from the clash between Achilles and Hector at the end of the Trojan War has been unearthed at Rutland in the East Midlands. It is one of only a handful of mosaics with this motif known to survive and the rest are on continental Europe. This is the first mosaic depicting Achilles and Hector ever discovered in the UK.

The presence of the mosaic was first discovered last year by Jim Irvine on a family walk on his father’s land. He saw some Roman pottery fragments in a wheat field. When he examined satellite imagery of the spot, he saw a cropmark delineating a building beneath the surface. A little digging revealed a small section of a mosaic. Irvine notified Leicestershire County Council and county archaeologists followed up, excavating a small trench to get a better idea of the mosaic beneath the surface. They were able to determine that the mosaic was in good condition and was figural with people, horses and chariots.

That type of complex figural imagery is rare in Britain, and experts from the University of Leicester Archaeological Services were enlisted to document the mosaic exposed in the trench in August 2020. The trench was then expanded, revealing additional figures that identified the mosaic as containing scenes from the Trojan War. After a year of lockdown and fieldwork backlog, archaeologists and students from the University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History returned to the site this September to excavate the full mosaic floor.

That type of complex figural imagery is rare in Britain, and experts from the University of Leicester Archaeological Services were enlisted to document the mosaic exposed in the trench in August 2020. The trench was then expanded, revealing additional figures that identified the mosaic as containing scenes from the Trojan War. After a year of lockdown and fieldwork backlog, archaeologists and students from the University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History returned to the site this September to excavate the full mosaic floor.

It is enormous, 36 feet by 23 feet, and was likely a grand dining room. Within a guilloche pattern border are three comic-book style panels showing the clash between Greek hero Achilles and Prince Hector of Troy. The top panels depicts the chariot battle between Achilles and Hector. The middle panel shows Achilles dragging

It is enormous, 36 feet by 23 feet, and was likely a grand dining room. Within a guilloche pattern border are three comic-book style panels showing the clash between Greek hero Achilles and Prince Hector of Troy. The top panels depicts the chariot battle between Achilles and Hector. The middle panel shows Achilles dragging  Hector’s corpse behind his chariot while Hector’s father, King Priam, begs Achilles to return the body for proper burial. The third panel features the exchange of Hector’s body for its weight in gold. A Trojan servant balances a huge scale on his shoulders with Hector’s corpse on one side and a bowl of gold on the other. Priam adds more gold vessels to meet the ransom requirement.

Hector’s corpse behind his chariot while Hector’s father, King Priam, begs Achilles to return the body for proper burial. The third panel features the exchange of Hector’s body for its weight in gold. A Trojan servant balances a huge scale on his shoulders with Hector’s corpse on one side and a bowl of gold on the other. Priam adds more gold vessels to meet the ransom requirement.

This last panel proves that the source was not actually The Iliad, because Homer’s account of the death of Hector has Priam ransoming the body with a cart full of rich gifts after he begs Achilles to think of his own father and have mercy. Before that plea softened his heart, Achilles had said he would never give the body back not even for its weight in gold. The story of the scale with Hector’s body on one side and a pile of gold on the other comes from a lost play by Aeschylus (Phrygians, or the Ransom of Hector) now known only from marginalia and fragments.

This last panel proves that the source was not actually The Iliad, because Homer’s account of the death of Hector has Priam ransoming the body with a cart full of rich gifts after he begs Achilles to think of his own father and have mercy. Before that plea softened his heart, Achilles had said he would never give the body back not even for its weight in gold. The story of the scale with Hector’s body on one side and a pile of gold on the other comes from a lost play by Aeschylus (Phrygians, or the Ransom of Hector) now known only from marginalia and fragments.

The room was part of a large villa in use between the 3rd and 4th century. While only the mosaic room and another building next to it have been excavated so far, geophysical surveys have found numerous outbuildings — barns, a circular structure, a possible bath house. It was probably the villa of a wealthy, classically educated individual. Fire damage and later burials indicate the villa was reused after it was abandoned.

The room was part of a large villa in use between the 3rd and 4th century. While only the mosaic room and another building next to it have been excavated so far, geophysical surveys have found numerous outbuildings — barns, a circular structure, a possible bath house. It was probably the villa of a wealthy, classically educated individual. Fire damage and later burials indicate the villa was reused after it was abandoned.

The mosaic is highly detailed, and specific features show that it is the work of highly skilled mosaicists. The range of colours used, the attention to fine detail and the way that some figures transgress the guilloche boundaries suggest that this presumably high status floor may have been sourced from an illuminated manuscript that was in the possession of the villa owner. It also raises the possibility that this person had an understanding of the classics and wanted to share that knowledge with their friends and guests.

Leicestershire Fieldworkers will be hosting a zoom webinar on the mosaic by one of the excavations’ lead archaeologists, Jennifer Browning, on Thursday, December 2nd, at 7.30PM GMT (2:30PM EST). Register here.