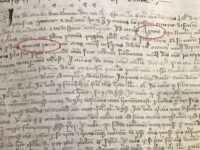

Researchers at the State Archive of Venice have discovered that the explorer Marco Polo had a previously unknown daughter named Agnese. The sole surviving record of her existence is a fragment of her will. It is dated July 7th, 1319, and names as fideicommissarii (executors) her husband Nicoletto Calbo, her father Marco Polo and another relative, Stefano Polo.

Researchers at the State Archive of Venice have discovered that the explorer Marco Polo had a previously unknown daughter named Agnese. The sole surviving record of her existence is a fragment of her will. It is dated July 7th, 1319, and names as fideicommissarii (executors) her husband Nicoletto Calbo, her father Marco Polo and another relative, Stefano Polo.

“Agnese’s testament,” says [Ca’ Foscari University researcher] Marcello Bolognari, “depicts an intimate and affectionate portrait of family life. She mentions her husband Nicolò, known as Nicoletto, as well as their children Barbarella, Papon (i.e. “Big Eater”) and Franceschino. The diminutives that she used to refer to her children tell us that this young mother wanted to leave something behind for her husband and children, but also — as the document shows — for the children’s tutor (magister) Raffaele da Cremona, their godmother (santola) Benvenuta, and the maid (famula) Reni.”

Before this discovery, Marco was recorded as having had three daughters — Fantina, Bellela and Moreta — with his wife Donata Badoer, but Agnese’s birth predates his marriage in 1300. Marco Polo returned to Venice from his epic voyage east in 1295. He was taken prisoner in 1298 after a naval battle between Venice and Genoa and was released from Genoese prison in 1299, so there is a very brief window for Agnese’s possible birth year.

Before this discovery, Marco was recorded as having had three daughters — Fantina, Bellela and Moreta — with his wife Donata Badoer, but Agnese’s birth predates his marriage in 1300. Marco Polo returned to Venice from his epic voyage east in 1295. He was taken prisoner in 1298 after a naval battle between Venice and Genoa and was released from Genoese prison in 1299, so there is a very brief window for Agnese’s possible birth year.

As far as we know, he only married the one time, which might explain why Agnese was kept so firmly on the down-low that we only found out about her 700 years later. That’s not to say she was necessarily born out of wedlock. Her will does not mention a mother, but it’s possible the mother may have died when Agnese was a baby, leaving Marco a widower. If they were married, however, there are no known records of it, nor is there evidence of Marco raising his first daughter with her stepmother and half-sisters. We know from her will that she did live in the same neighborhood (the contrada or parish of St. John Chrysostom Church) as her father and the rest of the extended Polo family.

Marco died less than four years after Agnese wrote her will. He had a will drawn on up while he was on his deathbed, appointing his wife and their three daughters co-executors. His will was detailed with several individual bequests. Agnese is not named. Again, that doesn’t necessarily imply a secondary status, given that she was sick enough to write a will in 1319 when she was in her early 20s and in all likelihood died before her father’s final illness.

It’s only a slight tangent to note that issues related to Marco Polo, his daughters and wills come up in a big way in the Venice state archives later in the century. In 1366, Fantina, Marco’s eldest daughter with his wife took the family of her deceased husband to court for stealing the vast sums she had inherited from her father who had returned from the court of Kublai Khan absolutely laden with riches and made even more upon his return working in the family trading business.

The inheritance was not marital property — a rare jolt of economic autonomy for a married woman at the time — but her snake of a husband Marco Bragadin just snatched it out from under her and then had the gall to leave “his” wealth to his snake family. They refused to return it to her and entrusted it to the custody of two Venice magistrates acting as administrators of the late Marco Bragadin’s assets.

The inheritance was not marital property — a rare jolt of economic autonomy for a married woman at the time — but her snake of a husband Marco Bragadin just snatched it out from under her and then had the gall to leave “his” wealth to his snake family. They refused to return it to her and entrusted it to the custody of two Venice magistrates acting as administrators of the late Marco Bragadin’s assets.

Fantina, who by then was 65 years old, was not having it. Defying her powerful in-laws and the magistrates who obviously now had a huge vested interest in seeing Fantina continue to be cut off from her inheritance, she and her lawyer presented her father’s will, a full inventory of his treasures and all the evidence that they had been stolen from her to judges Marco Dandolo, Giovanni Michiel and Natale Ghezzo. The Polo inheritance recorded in the records of the suit includes 40 horse silks, six silver belts, 12 carpets, bolts of Chinese silk, 16 garments in vermillion silk woven with gold thread, 91 other silk garments, a bag of cashmere, 537 chests with amber beads, a large gold table, rings of gold, silver, ruby and turquoise, a sack of aloe wood and one piece of silk described as “almost changing color.”

After a long court battle, the judges ruled in her favor, not just against the Bragadin family, but against their fellow magistrates, the estate administrators Andrea Contarini and Niccolò Morosini. The Bragadin’s had to reimburse her in full for her purloined inheritance and Contarini and Morosini had to pay her legal costs in the amount of nine gold ducats.