The remains of dozens of young men found in mass graves at the site of a defunct medieval castle moat in Vianen, central Netherlands, have been identified as British soldiers from the late 18th century.

The graves were discovered in November 2020 during drainage work to separate rainwater from sewage in the historic center of Vianen. To extend the city’s canal, municipal authorities chose the site of the former Batestein Castle (built in 1370 and abandoned after a fire in 1696) which had once had a moat on the south side of the grounds. Bones were found during the moat dig. At first it was just a few bones from one or two skeletons at most, but as they dug, they just kept finding more. Two weeks after the excavation began, the team had unearthed the skeletal remains of 44 individuals. By the end of January, the tally had risen to 81. In total, 82 skeletons were found in three mass grave pits.

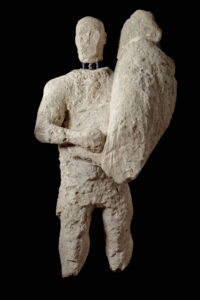

Some of the bodies had been stacked, and the presence of hand-forged nails suggested a few had been interred in coffins, perhaps shared coffins. Preliminary osteological examination found the remains belonged to young males in their teens and early 20s. There were some indications of sharp-force trauma on two skeletons, suggesting the young men may have fallen in battle.

To date the remains, identify any additional traces of violence and their possible national origin, the bones were recovered and transferred to specialized laboratories in the UK. Forensic anthropologists discovered that the sharp-force trauma was not from a violent battle, but rather from a bone saw, likely deployed during an autopsy. What was endemic among the skeletons was not evidence of violence, but evidence of one or more infections, including meningitis, pneumonia, sinus infections and a non-specific whole-body inflammation. The bones also showed consistent signs of poverty in childhood marked by malnutrition and hard labor.

Radiocarbon dating found the bodies were buried later than initially hypothesized, the late 18th century rather than the 15th or 16th. Archival research confirmed that a field hospital was set up in the ruins of Batestein Castle during the First Coalition War (1792-1797) when European forces (allied English, Dutch, Spanish, Austrian and Prussian troops) fought against the army of Revolutionary France.

Samples were taken from six of the skeletons and isotope analysis of their bones concluded that one came from southern England, possibly Cornwall, another from southern Cornwall and a third from an urban English environment. Two more may have been from the Netherlands but of possible English descent while the other was from Germany.

The men would have been treated at a field hospital at Batestein Castle in Vianen. As it was a mass grave and they all died under the same circumstances, a sample of six was sufficient, archaeologist Hans Veenstra told the BBC. […]

From late 1794-95, British soldiers were treated a short distance from the mass grave, and the researchers believe that the poor and cramped conditions of army life led to reduced resistance to bacterial infection.

The average age of the adult victims was about 26 although some of those who died were just teenagers. Around 60% showed traces of one or more infections which all had one cause – pneumococcal bacteria.