A hoard of hack silver from the Viking era (8th-11th c.) has been discovered in Stjørdal, central Norway. It consists of 46 objects, all of them silver. Only two of them are intact — whole finger rings — while the rest are broken pieces of coins, bracelets, a braided necklace, chains and wire. They were collected and cut or broken to use for the silver weight. Most examples of hack silver hoards found in Scandinavia contain a fragment from each larger object. This hoard is unusual for containing several fragments from the same object.

A hoard of hack silver from the Viking era (8th-11th c.) has been discovered in Stjørdal, central Norway. It consists of 46 objects, all of them silver. Only two of them are intact — whole finger rings — while the rest are broken pieces of coins, bracelets, a braided necklace, chains and wire. They were collected and cut or broken to use for the silver weight. Most examples of hack silver hoards found in Scandinavia contain a fragment from each larger object. This hoard is unusual for containing several fragments from the same object.

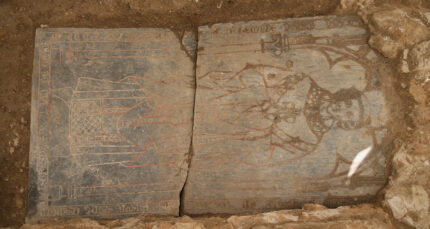

The hoard was discovered last December by metal detectorist Pawel Bednarski. He found the two small silver rings first, then more and more pieces began to emerge. Ultimately Bednarski pulled 46 objects from the ground, all of them barely buried between an inch and three inches beneath the surface. After rinsing the clay off of one of the pieces, he realized he had found something of archaeological importance and reported the discovery to municipal authorities.

The hoard was discovered last December by metal detectorist Pawel Bednarski. He found the two small silver rings first, then more and more pieces began to emerge. Ultimately Bednarski pulled 46 objects from the ground, all of them barely buried between an inch and three inches beneath the surface. After rinsing the clay off of one of the pieces, he realized he had found something of archaeological importance and reported the discovery to municipal authorities.

This is a rather exceptional find. It has been many years since such a large treasure find from the Viking Age has been made in Norway, says archaeologist and researcher Birgit Maixner at the NTNU Science Museum. […]

This find is from a time when silver pieces that were weighed were used as means of payment. This system is called the weight economy, and was in use in the transition between the barter economy and the coin economy, explains Maixner.

The coin economy in continental Europe continued even after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but in Norway there were no coins minted until the late 9th century. It was a barter economy until the end of the 8th century when the weight economy began to take hold. It was far more agile than barter because instead of having to manage the bulk of goods to be traded, small pieces of silver are easily packed and carried. Valuation is also far easier, requiring nothing more than a scale.

The coin economy in continental Europe continued even after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but in Norway there were no coins minted until the late 9th century. It was a barter economy until the end of the 8th century when the weight economy began to take hold. It was far more agile than barter because instead of having to manage the bulk of goods to be traded, small pieces of silver are easily packed and carried. Valuation is also far easier, requiring nothing more than a scale.

The total of the silver weight in the hoard is 42 grams, which according to the Gulating Act (a collection of Norwegian land laws dating back to around 900 A.D.) would buy you .6 of a cow. Most of the objects weighed less than a gram, so it seems likely they had already been used as currency. Was this perhaps the change drawer of a merchant?

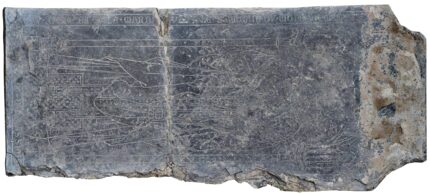

[T]he find contains an almost complete wide, band-shaped bangle, divided into eight pieces. Such broadband bangles, as archaeologists call them, are thought to have been developed in Denmark in the 8th century.

“We can imagine that the owner has prepared for trading by dividing the silver into appropriate weight units. That the person in question had access to entire broadband bracelets, a primary Danish object type, may indicate that the owner was in Denmark before the person traveled up to the Stjørdal area,” says Maixner.

Another unusual feature is the age of the Arabic coins. In an average Norwegian treasure find from the Viking Age, approx. three quarters of the Islamic coins minted between 890 and 950 AD. Only four out of seven coins from this find have been dated, but these date from the end of the 8th century or the beginning of the 8th century to some time in the 8th century.

“The relatively high age of the Islamic coins, broadband bracelets and the large degree of fragmentation of most of the objects is more typical of treasure finds from Denmark than from Norway. These features also make it likely to assume that the treasure is from around 900 AD,” explains Maixner.