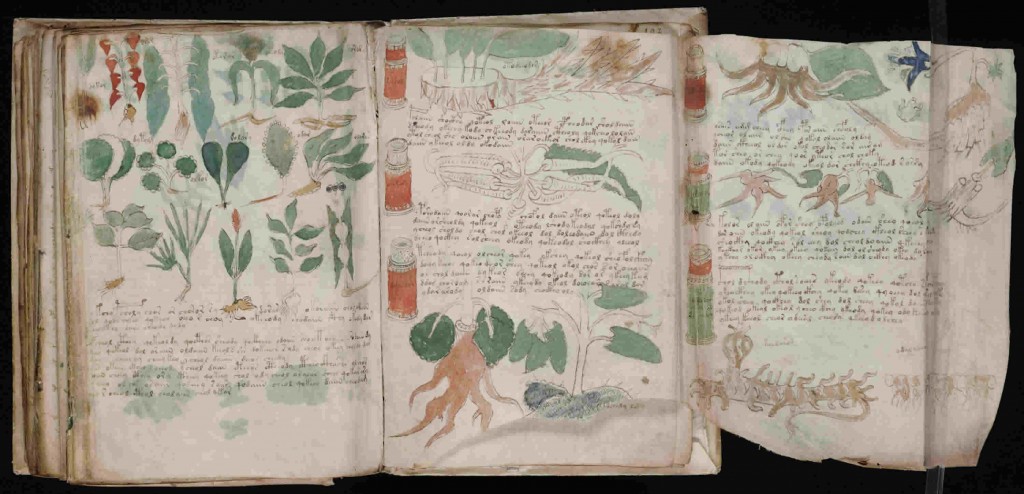

The Voynich Manuscript, a book written in an unknown language with mysterious botanical illustrations,  has yet to be cracked, despite centuries of scholarly research and regular “this time they’ve done it!” headlines that turn out to be dead ends. The contents of the book have taken the lion’s share of researchers’ attention, but the origins and ownership history of the manuscript are just as mysterious. A new study has revealed the name of an earlier owner to fill in one of the many blanks in this book’s history.

has yet to be cracked, despite centuries of scholarly research and regular “this time they’ve done it!” headlines that turn out to be dead ends. The contents of the book have taken the lion’s share of researchers’ attention, but the origins and ownership history of the manuscript are just as mysterious. A new study has revealed the name of an earlier owner to fill in one of the many blanks in this book’s history.

The manuscript got its name relatively recently in its long history, when it was rediscovered in 1912 at the Jesuit College at Frascati near Rome by Polish antiquarian and book dealer Wilfrid Voynich. The vellum pages radiocarbon date the folio to between 1404 and 1438, but the earliest reference to it on the historical record dates to 1639. It’s a letter from Prague alchemist Georg Baresch to Jesuit linguist Athanasius Kircher. Baresch was the owner of the manuscript at that time, and sent a copy of the glyphs to Kircher hoping he might be able to translate. Kircher was just as unsuccessful as everyone else who has tried, but he was hooked and wanted to buy it. Baresch refused.

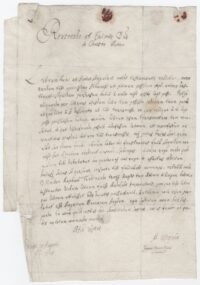

Kircher ultimately did receive the book when Baresch’s good friend Jan Marek Marci inherited the manuscript and forwarded it to Kircher in 1665. The letter Marci wrote to Kircher contains another precious hint to the manuscript’s ownership history. He said that the book had at one point been bought by Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (r. 1576-1612) for the enormous sum of 600 ducats.

Kircher ultimately did receive the book when Baresch’s good friend Jan Marek Marci inherited the manuscript and forwarded it to Kircher in 1665. The letter Marci wrote to Kircher contains another precious hint to the manuscript’s ownership history. He said that the book had at one point been bought by Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (r. 1576-1612) for the enormous sum of 600 ducats.

The problem is there is no evidence in the imperial archives that Rudolf acquired this expensive enigma. The budget for the imperial librarian at that time was 1000 florins (another gold coin with equivalent value to the ducat) over three years, so dropping 600 on one book would have been out of bounds. The manuscript does not appear on any inventories in the public imperial library or in the Emperor’s personal library, nor does it appear in any records of the Royal Swedish Library after Swedish troops looted the Emperor’s library in 1648.

Now, after scouring imperial account journals kept by Rudolf’s court, Stefan Guzy of the University of the Arts Bremen, Germany, has identified records that could shed further light on the manuscript’s sale to the emperor, tracing its ownership back a little further.

“My idea was to compile all book-related transactions by analysing the imperial account books of the Hofkammer (Imperial Chamber) in Vienna and Prague, where all ingoing and outgoing letters were registered,” Guzy says. “If there was any transaction involving 600 gold coins, then the chance was pretty high that this acquisition was the one mentioned in the Marci letter.”

Luckily, out of almost 7,000 journal entries, including 126 book transactions, only one case involved a book sale for 600 gold coins.

The records revealed that in 1599, the physician Carl Widemann sold a collection of manuscripts to Rudolf for 500 silver thaler, an amount cited in another record by its equivalent in gold, 600 florin—another type of gold coin. A further record refers to the collection as “remarkable/rare books” and that they were transported in a small barrel, Guzy writes….

“Almost all of the emperor’s money transactions were made in guilders (florin), usually Rhenisch guilders, with only very few in thaler or ducats; so I believe that the information in the [Marci] letter was just meant to be ‘gold coins,’ which both florin and ducats are,” Guzy says. “Even if a deal was made with ducats or thaler, florins were usually used for the final transaction.”

Guzy even has a possible candidate for the owner of the manuscript before Widemann. Widemann lived in the home of Leonard Rauwolf, a 16th century Bavarian botanist and physician who was the first in the modern era to collect and document the flora of the Near East. They appear to have been related in some way, and Widemann may have inherited Rauwolf’s books after his death as that is when he started selling books to the Emperor. The Voynich Manuscript with all its fanciful plant illustrations would of course have been of great interest to a botanist.

Stefan Guzy’s research has been published (pdf) in the proceedings of the first International Conference on the Voynich Manuscript 2022. You can attempt to decipher it yourself by browsing the digitized pages of the manuscript on Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library website.