Archaeologists in Germering, Upper Bavaria, have unearthed the well-preserved remains of a wooden well from the Bronze Age filled with ritual deposits. It is more than 3,000 years old.

Archaeologists in Germering, Upper Bavaria, have unearthed the well-preserved remains of a wooden well from the Bronze Age filled with ritual deposits. It is more than 3,000 years old.

“It is extremely rare for a well to survive more than 3,000 years so well. Its wooden walls have been completely preserved at the bottom and are still partly damp from the groundwater. This also explains the good condition of the finds made from organic materials, which are now being examined more closely. We hope this will provide us with more information about the everyday life of the settlers of the time,” adds Dr. Jochen Haberstroh, responsible archaeologist at the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments.

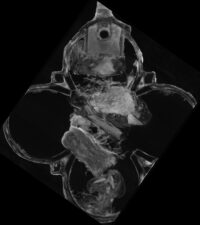

Inside the well, archaeologists discovered 26 bronze garment pins, amber beads, two metal spirals, an animal tooth wrapped in metal to make a pendant, and more than 70 ceramic vessels. The vessels are high quality, finely wrought, decorated bowls, cups and pots. These were not everyday use objects, but rather expensive wares typically found in graves from the Middle Bronze Age (1800-1200 B.C.). The condition they were found in at the bottom of the well indicates they were lowered carefully into the water, not dropped or thrown.

Inside the well, archaeologists discovered 26 bronze garment pins, amber beads, two metal spirals, an animal tooth wrapped in metal to make a pendant, and more than 70 ceramic vessels. The vessels are high quality, finely wrought, decorated bowls, cups and pots. These were not everyday use objects, but rather expensive wares typically found in graves from the Middle Bronze Age (1800-1200 B.C.). The condition they were found in at the bottom of the well indicates they were lowered carefully into the water, not dropped or thrown.

The remains of Bronze Age settlements have been found before in the Germering area, and more than 70 wells ranging in date from the Bronze Age to the early Middle Ages. The newly-discovered well would originally have been more than five meters (16.4 feet) deep, significantly deeper than the others, evidence that it was in use at a time when the water table had dropped likely due to an extended period of drought. The hardships of the drought may have spurred the residents to sacrifice their valuables in the well to appease their emotionally unavailable deities.

The remains of Bronze Age settlements have been found before in the Germering area, and more than 70 wells ranging in date from the Bronze Age to the early Middle Ages. The newly-discovered well would originally have been more than five meters (16.4 feet) deep, significantly deeper than the others, evidence that it was in use at a time when the water table had dropped likely due to an extended period of drought. The hardships of the drought may have spurred the residents to sacrifice their valuables in the well to appease their emotionally unavailable deities.

Since the beginning of 2021, archaeologists have been working in advance of construction work for a letter distribution center on the area where the well has now been discovered. The excavations are among the largest area excavations of the past year in Bavaria. In the meantime, the scientists there have been able to document around 13,500 archaeological finds, mainly from the Bronze Age and the early Middle Ages. Some of the finds are currently being examined and conserved at the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments. After completion of the subsequent restoration work, these are expected to be made accessible to science and the public at the end of the year in the Germering City Museum.