Suetonius (69-122 A.D.) wrote in The Lives of the Caesars that Augustus could accurately boast that he had found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble. The context of the statement was the improvements to the city Augustus had made as sole ruler after he abandoned any idea of restoring the Roman Republic and instead subsumed all the major magistracies of the Senate, Tribunician powers and the entire treasury of Rome under his personal control.

The city, which was not built in a manner suitable to the grandeur of the empire, and was liable to inundations of the Tiber, as well as to fires, was so much improved under his administration, that he boasted, not without reason, that he “found it of brick, but left it of marble.”

Cassius Dio (155-235 A.D.) attributes the same quote to Augustus (Roman History, Book LVI:30), only he explicitly rejects the literal interpretation proffered by Suetonius.

“I found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble.” [Augustus] did not thereby refer literally to the appearance of its buildings, but rather to the strength of the empire.

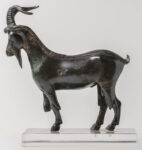

A new exhibition at the Capitoline Museums‘ Palazzo Caffarelli presents a whole new view of that Republican city of clay via more than 1800 archaeological remains, most of which have never before been on display. There are bronze pieces, local stone and a tiny smattering of marble, but the overwhelming majority of the objects are made of terracotta and ceramic; ie, the clay/brick that Augustus was so proud of replacing.

A new exhibition at the Capitoline Museums‘ Palazzo Caffarelli presents a whole new view of that Republican city of clay via more than 1800 archaeological remains, most of which have never before been on display. There are bronze pieces, local stone and a tiny smattering of marble, but the overwhelming majority of the objects are made of terracotta and ceramic; ie, the clay/brick that Augustus was so proud of replacing.

Many of these works are fragmentary, recovered at various times at locations within the city and in its environs, but most of them were recovered from the sites of ancient temples on the Capitoline Hill and in the Campus Martius. They date to between the 6th century B.C. and the middle of the 1st century B.C., the heyday of the Roman Republic.

Many of these works are fragmentary, recovered at various times at locations within the city and in its environs, but most of them were recovered from the sites of ancient temples on the Capitoline Hill and in the Campus Martius. They date to between the 6th century B.C. and the middle of the 1st century B.C., the heyday of the Roman Republic.

The exhibition focuses on the material remains that attest to the physical construction of the city, and curators used the latest technology to attempt to reconstruct how some of these fragments would have looked when intact during the Republic. For example, chunks of terracotta cladding slabs from a temple in what is now Largo Argentina (of cat shelter fame) have been set into a background image illustrating what the vividly-painted terracotta frieze would have looked like.

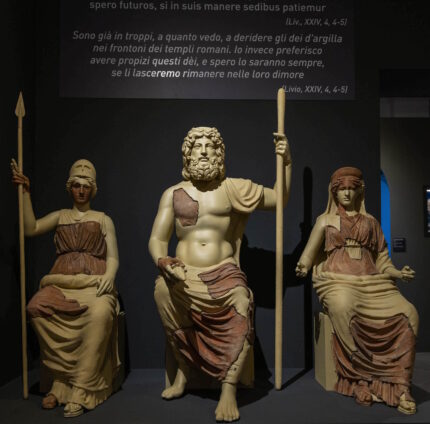

One group of largely ignored objects — pieces of terracotta figures discovered in the 19th century on the Via Latina leading south out of Rome — stands out for the high quality of craftsmanship and the importance to their religious function. Researchers determined that the 11 pieces were part of sculptures of the Capitoline Triad (deities Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) that adorned a temple pediment in the 1st century B.C. They then recreated the full-size sculptures by 3D-printing what was lost and integrating the original fragments into the reproduction in their proposed original locations. It’s a striking presentation that deploys technology in an innovative way to showcase fragmentary materials as close as possible to their original state.

One group of largely ignored objects — pieces of terracotta figures discovered in the 19th century on the Via Latina leading south out of Rome — stands out for the high quality of craftsmanship and the importance to their religious function. Researchers determined that the 11 pieces were part of sculptures of the Capitoline Triad (deities Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) that adorned a temple pediment in the 1st century B.C. They then recreated the full-size sculptures by 3D-printing what was lost and integrating the original fragments into the reproduction in their proposed original locations. It’s a striking presentation that deploys technology in an innovative way to showcase fragmentary materials as close as possible to their original state.

The Rome of the Republic exhibition is open now and runs through September 24th of this year.