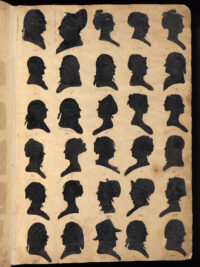

A ledger book containing 1,800 cut-paper silhouette portraits made by English immigrant William Bache in the early 1800s has been digitized by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Portraits of luminaries like George and Martha Washington keep company with Virginia tavern keepers and Caribbean priests, people from all income levels and professions.

A ledger book containing 1,800 cut-paper silhouette portraits made by English immigrant William Bache in the early 1800s has been digitized by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Portraits of luminaries like George and Martha Washington keep company with Virginia tavern keepers and Caribbean priests, people from all income levels and professions.

This unique record of Federal-era social history was acquired by the NPG in 2002. In 2008, conservators discovered that the album contained arsenic which made it unsafe for display, never mind allowing researchers to leaf through it, a’ la The Name of the Rose.

The National Portrait Gallery used Getty’s support to overcome these limitations by fully digitizing the entire volume. Robyn Asleson, the lead curator and curator of prints and drawings at the National Portrait Gallery, also completed extensive research that confirms the identities of hundreds of sitters in New Orleans and generates a new understanding of traveling portrait artists at the turn of the 19th century. […]

Asleson and research assistant Elizabeth Isaacson scanned through Ancestry.com, digitized newspapers, history books, baptismal records, wills and other legal documents to unveil the identity of sitters, including many of Afro Caribbean descent for whom no other likeness is known to exist. Users of the microsite can now “flip” through pages of the album and click on high-res images of each portrait to learn the sitter’s full name, lifespan or years active and the date their portrait was created.

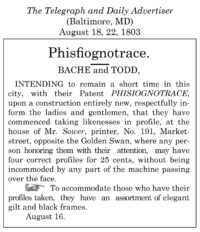

William Bache had no artistic training, but he was able to develop a successful career as a silhouette maker, traveling to cities all over the eastern seaboard of the United States and reaching as far south as Cuba. He used his own patented version of a physionotrace, a mechanical drawing frame first invented in France in the waning days of the Ancien Régime, to capture the outline of people’s profiles and reproduce them quickly and cheaply. His newspaper advertisements emphasized the cheap part, offering “four correct profiles for 25 cents,” about $5 in today’s money.

The fixed features of the face like the shape of the nose, jaw and brow were subject of intense study in the late 18th century. Pioneered by Swiss poet and minister Johann Kaspar Lavater, author of the seminal work on physiognomy (1775-1778), the pseudoscientific pursuit correlated the physical features of the face to a person’s character and personality. In order to document the physiognomy of an individual in the most objective way possible, Lavater advocated tracing the “lines of countenance,” the contours of a person’s head and face, to measure their proportions and angles and thereby “scientifically” determine their character.

The fixed features of the face like the shape of the nose, jaw and brow were subject of intense study in the late 18th century. Pioneered by Swiss poet and minister Johann Kaspar Lavater, author of the seminal work on physiognomy (1775-1778), the pseudoscientific pursuit correlated the physical features of the face to a person’s character and personality. In order to document the physiognomy of an individual in the most objective way possible, Lavater advocated tracing the “lines of countenance,” the contours of a person’s head and face, to measure their proportions and angles and thereby “scientifically” determine their character.

To ensure the most accurate possible record of the lines of countenance, Lavater devised a method to trace a profile from life by mounting a wood frame to the side of a chair. The subject sat facing forward, gripping the frame and its rigid mounts to stay as still as possible. A piece of tracing paper was fitted into the frame and a candle lit on the other side of the chair. He would then trace the shadow cast by her face onto the paper.

An even greater leap forward in removing artistic interpretation from portraiture was achieved by engineer and engraver Gilles-Louis Chrétien in 1784. He invented the physionotrace, a wooden frame large enough for a person to sit in turned to the side. The person’s chin was supported and fixed the head so it would not move. The artist/machinist would then trace a life-sized or scale portrait using a pencil connected via a metal arm to another pencil that made a copy on a separate sheet of paper.

Within a week, that drawing could be quickly reproduced in scaled-down sizes. They became a popular fashion trend in the French Revolutionary and First Empire period. Sitters would buy portrait packages of the large likeness and smaller prints, which could be filled in with extremely precise details. Each portrait was identical, unlike the painted portrait miniatures.

This mechanism was very well-suited to the production of silhouettes. You got an outline of the profile on the spot, and an easy and fast means to reproduce the exact profile on a smaller scale. Unfortunately the patent records of Bache’s 1803 physiognotrace were destroyed in an 1836 fire, so we don’t know exactly what his machine was like. His partner Isaac Todd wrote that it was different from its predecessors in its ability to “trace the human face with ‘mathematical correctness’ without touching it.”

This mechanism was very well-suited to the production of silhouettes. You got an outline of the profile on the spot, and an easy and fast means to reproduce the exact profile on a smaller scale. Unfortunately the patent records of Bache’s 1803 physiognotrace were destroyed in an 1836 fire, so we don’t know exactly what his machine was like. His partner Isaac Todd wrote that it was different from its predecessors in its ability to “trace the human face with ‘mathematical correctness’ without touching it.”

Flip through the digitized Ledger Book of William Bache’s silhouettes on this website. Each silhouette is clickable for individual identification. You can also navigate it by name using the index.