For the first time, muon radiography has been used to discover a Hellenistic burial chamber under the busy streets of Naples. The cosmic particles found the hypogeum 32 feet beneath the densely populated Sanità district in the city center.

For the first time, muon radiography has been used to discover a Hellenistic burial chamber under the busy streets of Naples. The cosmic particles found the hypogeum 32 feet beneath the densely populated Sanità district in the city center.

Ancient Neapolis was founded by Greek colonists in the 9th century B.C. and maintained Greek cultural traditions even after it was conquered by Rome in the 4th century B.C. The undercarriage of the city is honeycombed by hypogea where the elite were buried in a network of tunnels and chambers carved out of the volcanic tufa between the 6th and 3rd centuries B.C.

Neapolis’ necropoli were buried by mudslides in Late Antiquity and as the city layered itself upwards, the hypogea were forgotten for centuries. A select few were found during construction of cisterns and bomb shelters or rediscovered under private property, including the ornately Ipogeo dei Cristallini which recently opened to the public for the first time. The vast majority are still buried 30+ feet below street level, unreachable by traditional archaeological excavation due to the highly populated and densely constructed city.

So if the hypogea cannot be unearthed, how can they be studied? Enter muons. Muons are dense, high-energy particles produced in the upper layers of the atmosphere that constantly shower the earth’s surface. They are capable of penetrating much thicker materials than X-rays can, and size is no object. For example, muon radiography is used in the monitoring of volcanoes, including Vesuvius whose interior life is of particular interest to Naples five miles to its west.

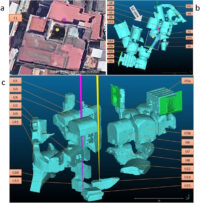

The hypogeum was discovered by installing two nuclear emulsion muon detectors, which require no power source to measure the differential flux of muons, in a cellar once used to age hams 60 feet below street level. The detectors were left to collect data for a month before the emulsion films were extracted and developed. By comparing the measured muon flux to the expected flux, scientists were able to map empty structures deep under the city and reconstruct the layers above them to determine the three-dimensional position of the chamber.

The hypogeum was discovered by installing two nuclear emulsion muon detectors, which require no power source to measure the differential flux of muons, in a cellar once used to age hams 60 feet below street level. The detectors were left to collect data for a month before the emulsion films were extracted and developed. By comparing the measured muon flux to the expected flux, scientists were able to map empty structures deep under the city and reconstruct the layers above them to determine the three-dimensional position of the chamber.

“The muons produced in the interaction of cosmic rays with the atmosphere penetrate buildings and the underlying rock and can pass through it until they reach the detectors. However, depending on the density and thickness of the rock crossed, a part of these muons is absorbed”, explains Valeri Tioukov, a researcher at the INFN of Naples , who coordinated the project. “From the number of muons arriving at the detector from different directions it is possible to estimate the density of the material they have passed through. We found an excess in the data that can only be explained by the presence of a new burial chamber,” concludes Tioukov.

“The presence of additional funerary hypogea hypothesized for many years is now confirmed by the results of muon radiography”, concludes Carlo Leggieri of Celanapoli , an association that looks after this site by promoting its recovery and use.

The study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports and can be read in its entirety here.