A collection of more than 400 pieces of Judaica and other prized possessions of Jewish families at the dawn of World War II have been discovered in Lodz, Poland. The treasure includes hanukkiahs, menorahs, sacred vessels and fragments of the Talmud, as well as household objects like silver-plate tableware, clothing and glass perfume bottles. They were wrapped in Polish, Yiddish and German newspapers that date to October of 1939.

A collection of more than 400 pieces of Judaica and other prized possessions of Jewish families at the dawn of World War II have been discovered in Lodz, Poland. The treasure includes hanukkiahs, menorahs, sacred vessels and fragments of the Talmud, as well as household objects like silver-plate tableware, clothing and glass perfume bottles. They were wrapped in Polish, Yiddish and German newspapers that date to October of 1939.

The treasure was discovered during renovation work on a hundred-year-old building at 23 Polnoczna Street. Nazi forces occupied Lodz in September of 1939, within a week of their invasion of Poland. They established a ghetto in northeastern Lodz in early February 1940. More than 150,000 Lodz Jews — the second largest Jewish population in Poland after Warsaw — were forced to move into an area of just 1.5 square miles. Polnoczna Street formed its southernmost boundary.

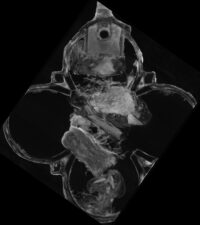

The cache was found last month inside a damaged wooden chest buried in the foundations of the building. An initial examination counted approximately 280 objects in the chest. When government archaeologists explored the find site after construction was suspended, they found the rest of the treasure.

The cache was found last month inside a damaged wooden chest buried in the foundations of the building. An initial examination counted approximately 280 objects in the chest. When government archaeologists explored the find site after construction was suspended, they found the rest of the treasure.

The timing of the discovery dovetailed with the Festival of Lights. The Jewish community of Lodz, which has offices on the same block of Polnoczna Street, celebrated the rediscovery of the treasure as part of its Hanukkah celebration, lighting two of the hanukkiahs on December 22nd.

“The discovery is remarkable, especially the quantity. These are extremely valuable, historic items that testify to the history of the inhabitants of this building,” said Agnieszka Kowalewska-Wójcik, director of the Board of Municipal Investments in Łódź, according to Polish media. She said the artifacts are being transferred to the city’s archaeological museum, adding, “I hope a special, generally accessible exhibition will be prepared.” […]

“For us archaeologists, such unusual finds are a challenge, but also a great joy. I don’t remember the last time such treasures were unearthed in Łódź.” said Bartłomiej Gwóźdź, a local archaeologist. “At the moment, each item is carefully cleaned so that nothing is damaged, broken or destroyed.”