The remains of an early 19th century London workhouse suggest that it did not start out the bleak, uncomfortable environment so vividly described by Charles Dickens and other Victorian writers. The plastered walls were painted a soothing light blue; the rooms were heated with fireplaces; even hot water bottles were available.

The remains of an early 19th century London workhouse suggest that it did not start out the bleak, uncomfortable environment so vividly described by Charles Dickens and other Victorian writers. The plastered walls were painted a soothing light blue; the rooms were heated with fireplaces; even hot water bottles were available.

Since early this year, archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) have been excavating the two-acre site before construction of a new state-of-the-art ophthalmology center. It is part of a five-acre site that includes St. Pancras Hospital, originally St. Pancras Workhouse, named after the neighboring Church of St. Pancras in what was then a suburb of London.

The workhouse was built in 1809 to accommodate 500 indigent people, often families. An infirmary was added three years later, and by the middle of the 19th century, the population of the workhouse had increased more than threefold, fluctuating between 1,500 and 1,900 at its peak. Additions to the workhouse and infirmary were built to keep up with the number of residents. The workhouse was finally shut down in 1929 and its surviving buildings folded into the hospital.

As the name suggests, the idea of the workhouse was that the state would provide relief to the poverty-stricken in the form of a roof over their heads and enough food to survive in exchange for their unpaid labor. Church parishes were part of the administration of relief initially and there was some flexibility in the treatment of indigent families and individuals. That came to an end with the 1834 Poor Law.

By the 1830s, conditions inside the workhouses were dangerous, cramped and prison-like. Infectious diseases were rampant, beds were crammed into every possible space and inmates worked long hours on industrial production lines. Other means of relief, like parish disbursements that did not require institutionalization, were discouraged and the poor encouraged to sell whatever scraps they still owned to be allowed into the workhouse. Children were separated from their parents and the workhouses turned to profitable enterprise administered by businessmen. All workhouse inmates, adults and children, were assigned to painful, repetitive hard labor like crushing bone to make fertilizer, or picking oakum.

By the 1830s, conditions inside the workhouses were dangerous, cramped and prison-like. Infectious diseases were rampant, beds were crammed into every possible space and inmates worked long hours on industrial production lines. Other means of relief, like parish disbursements that did not require institutionalization, were discouraged and the poor encouraged to sell whatever scraps they still owned to be allowed into the workhouse. Children were separated from their parents and the workhouses turned to profitable enterprise administered by businessmen. All workhouse inmates, adults and children, were assigned to painful, repetitive hard labor like crushing bone to make fertilizer, or picking oakum.

The area currently being investigated was known to have had some workhouse structures, but they did not survive. They were damaged in the Blitz and demolished after World War II. The MOLA team has been excavating the site where these buildings once stood and expected to find their foundations, ground floors and associated artifacts.

The new evidence suggests the St Pancras workhouse may have started out with a greater interest in support than deterrence. Williams said: “While the facilities are spartan, the inmates were not there to be punished … There were gardens, an infirmary and nursery. These acknowledge their needs as much as the heated rooms, or the pale blue paint on the walls.”

The finds include institutional crockery – with plates bearing an image of St Pancras and the words “Guardians of the Poor St Pancras Middlesex” – and the remains of a bone toothbrush with horsehair bristles, suggesting the importance of personal hygiene.

Inmate hygiene, comfort and even basic needs like a modicum of heat fell by the wayside after the Poor Law and the explosion of the population at St. Pancras. Henry Morley, a friend and collaborator of Charles Dickens, mentioned St. Pancras Workhouse in an article entitled The Frozen-Out Poor Law published in Dickens’ publication All the Year Round in February, 1861:

Inmate hygiene, comfort and even basic needs like a modicum of heat fell by the wayside after the Poor Law and the explosion of the population at St. Pancras. Henry Morley, a friend and collaborator of Charles Dickens, mentioned St. Pancras Workhouse in an article entitled The Frozen-Out Poor Law published in Dickens’ publication All the Year Round in February, 1861:

A woman, during the intense frost, was met in the evening carrying home her weekly quartern loaf from Saint Pancras Workhouse. (Was it not there that guardians of the poor, not long ago, excited wrath among parishioners by putting themselves on the parish for hot dinners at their weekly meetings?). The woman was met shivering with cold; she had been waiting for her dole, from twelve o’clock till half-past four, in a room with a stone floor, which she declared had not been warmed in any way. “I could have stood it better,” she said, “if there hadn’t been such a dreadful could draught from them wentilating places all round the floor.” The “ventilators” out of which the cold blast came, were the pipes of the disused warming apparatus. If was desirable to use that apparatus for the benefit of paupers, even when the thermometer wavered between freezing and zero. […]

A vestryman is asked whether this woman’s story, not the first or the tenth of its kind, could be true ; were the poor really exposed to so much suffering when they came for relief? “Yes,” he replied, ” and wilfully. I have tried to effect a change, but only three would side with me. The rest thought that if the poor creatures were made too comfortable, more would come.” We take our illustration from St. Pancras simply because it is natural for anybody to look to St. Pancras of evil repute, when he wishes to lay his hand on any sort of abuse incident to the administration of the Poor Law. But the illustration serves for the whole system, which makes workhouses discouragements to poverty, and gaols encouragements to crime.

The excavation of the ancient Etruscan and Roman sacred baths at San Casciano dei Bagni in Tuscany has unearthed another extraordinary treasure: a marble statue of Apollo Sauroctonos (Apollo Lizard-killer), depicting a youthful Apollo leaning against a tree about to catch a lizard climbing up the trunk. It’s a Roman copy of a bronze original by the renown Greek sculptor Praxiteles, one of about forty known to exist.

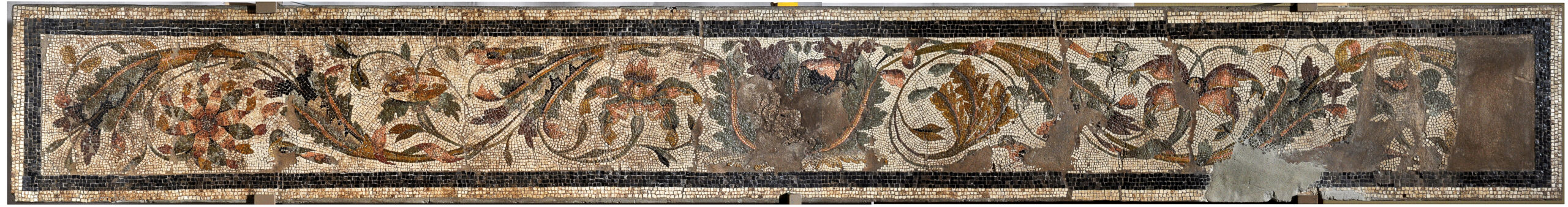

The excavation of the ancient Etruscan and Roman sacred baths at San Casciano dei Bagni in Tuscany has unearthed another extraordinary treasure: a marble statue of Apollo Sauroctonos (Apollo Lizard-killer), depicting a youthful Apollo leaning against a tree about to catch a lizard climbing up the trunk. It’s a Roman copy of a bronze original by the renown Greek sculptor Praxiteles, one of about forty known to exist. The statue of Apollo was discovered this summer on the edge of the Great Bath, the hot spring sacred to the Etruscans and Romans. Life-sized at around six feet high, it was broken into sections but the pieces are large and most of them have been recovered so that the statue can be reassembled almost entire.

The statue of Apollo was discovered this summer on the edge of the Great Bath, the hot spring sacred to the Etruscans and Romans. Life-sized at around six feet high, it was broken into sections but the pieces are large and most of them have been recovered so that the statue can be reassembled almost entire. Apollo was one of the major deities of the sanctuary. The hot springs and mineral waters were believed to cure illness, and the gods connected to health were worshipped there by people seeking cures. Apollo was the god of healing and diseases, so petitioners left votive offerings — coins, figurines, sculptures of afflicted body parts, effigies of the gods — to petition a cure for what ailed them. The lizard Apollo is hunting in the statue had medical relevance as well. Lizards were key ingredients in medications for diseases of the eye. Bronze votive figurines of lizards have been found in the San Casciano baths, offerings from people with ophthalmic complaints.

Apollo was one of the major deities of the sanctuary. The hot springs and mineral waters were believed to cure illness, and the gods connected to health were worshipped there by people seeking cures. Apollo was the god of healing and diseases, so petitioners left votive offerings — coins, figurines, sculptures of afflicted body parts, effigies of the gods — to petition a cure for what ailed them. The lizard Apollo is hunting in the statue had medical relevance as well. Lizards were key ingredients in medications for diseases of the eye. Bronze votive figurines of lizards have been found in the San Casciano baths, offerings from people with ophthalmic complaints. One of the extraordinary group of bronzes discovered in 2022 was a dancing Apollo figure from the oldest basin at the sanctuary. It likely dates to around 100 B.C. Based on its size and style, the marble Apollo Sauroctonos probably dates to the 2nd century A.D. It was broken in the early 5th century A.D., when the Christianization of the territory led to the temples and statuary being toppled into the basins and the sanctuary closed.

One of the extraordinary group of bronzes discovered in 2022 was a dancing Apollo figure from the oldest basin at the sanctuary. It likely dates to around 100 B.C. Based on its size and style, the marble Apollo Sauroctonos probably dates to the 2nd century A.D. It was broken in the early 5th century A.D., when the Christianization of the territory led to the temples and statuary being toppled into the basins and the sanctuary closed.