A New Kingdom cemetery with richly furnished burials and a complete papyrus has been discovered in Ghoreifa near the site of Tuna El Gebel in the Minya Governorate of Upper Egypt. Thousands of artifacts were unearthed from the rock-cut tombs. Inscriptions on the funerary objects and sarcophagi identify the deceased as the senior officials and high priests of the 15th nome of Upper Egypt under the pharaohs of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550 B.C.-1069 B.C.).

A New Kingdom cemetery with richly furnished burials and a complete papyrus has been discovered in Ghoreifa near the site of Tuna El Gebel in the Minya Governorate of Upper Egypt. Thousands of artifacts were unearthed from the rock-cut tombs. Inscriptions on the funerary objects and sarcophagi identify the deceased as the senior officials and high priests of the 15th nome of Upper Egypt under the pharaohs of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550 B.C.-1069 B.C.).

The site has been excavated every season since 2017 and the Egyptian archaeological mission has been looking for the New Kingdom cemetery of the 15th nome and its capital Ashmunin this whole time. It finally emerged in the most recent excavation that began last August in the northern section of the site. Rock-cut communal tombs contained the remains of the high priests of Djehuty, god of the moon and writing, and other senior officials, buried with an enormous array of goods.

The site has been excavated every season since 2017 and the Egyptian archaeological mission has been looking for the New Kingdom cemetery of the 15th nome and its capital Ashmunin this whole time. It finally emerged in the most recent excavation that began last August in the northern section of the site. Rock-cut communal tombs contained the remains of the high priests of Djehuty, god of the moon and writing, and other senior officials, buried with an enormous array of goods.

They include 16 tombs with five anthropoid limestone sarcophagi engraved with hieroglyphic texts and five well-preserved wooden coffins, some of which are decorated with the names and titles of their owners. The mission has also unearthed a collection of around 25,000 ushabti figurines made of blue and green faience, most of which are engraved with the titles of the deceased.

More than 700 amulets of various shapes, sizes, and materials have also been found, including heart scarabs, amulets of the gods, and amulets made of pure gold, such as the “Ba” and an amulet in the shape of a winged cobra.

Many pottery vessels of different shapes and sizes, which were used for funerary and religious purposes, have been unearthed, along with tools for cutting stones and moving coffins, such as wooden hammers and baskets made of palm fronds.

Two of the officials interred in the cemetery were Djehuty Mes, the overseer of the bulls of the Temple of Amun, and a woman named Nany, who bore the title “Djehuty’s singer.” Another was Tadi Ist, daughter of Eret Haru, the high priest of Djehuty in Ashmunin. The canopic vessels containing her organs were found in two wooden boxes next to her beautifully painted and carved coffin. The inner part of the lid of her sarcophagus is painted with figures representing the 12 hours and a central figure who bears a striking resemblance to Marge Simpson. Within the coffin, Tadi Ist’s mummified body wears a gilded mask and a delicate beaded dress in remarkably intact condition.

Two of the officials interred in the cemetery were Djehuty Mes, the overseer of the bulls of the Temple of Amun, and a woman named Nany, who bore the title “Djehuty’s singer.” Another was Tadi Ist, daughter of Eret Haru, the high priest of Djehuty in Ashmunin. The canopic vessels containing her organs were found in two wooden boxes next to her beautifully painted and carved coffin. The inner part of the lid of her sarcophagus is painted with figures representing the 12 hours and a central figure who bears a striking resemblance to Marge Simpson. Within the coffin, Tadi Ist’s mummified body wears a gilded mask and a delicate beaded dress in remarkably intact condition.

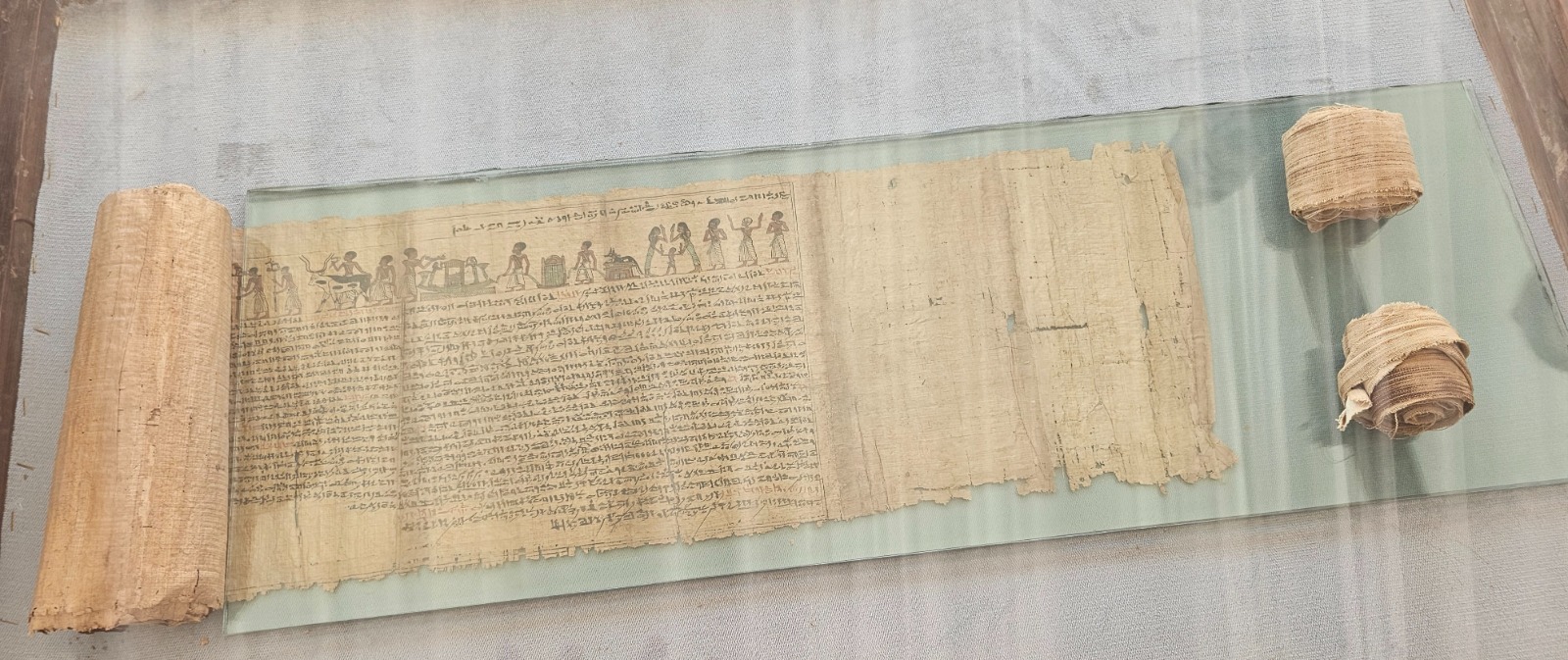

The papyrus is a Book of the Dead in an excellent state of preservation. It has not been fully unrolled yet, but archaeologists estimate it is between 40 and 50 feet long. It is the first complete papyrus found in the Al-Ghoraifa area. When it has been conserved and stabilized, it will go on display at the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo.