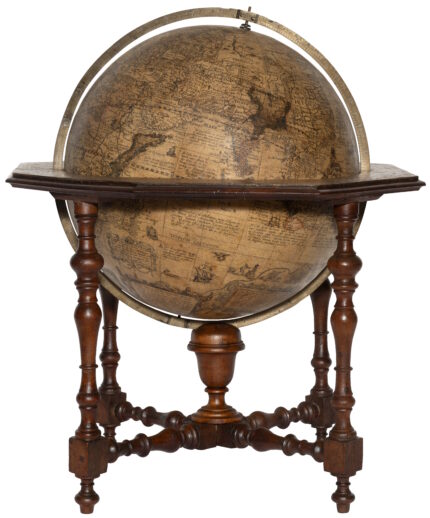

A rare 16th century globe has been restored and put on display at the Museo Galileo in Florence.

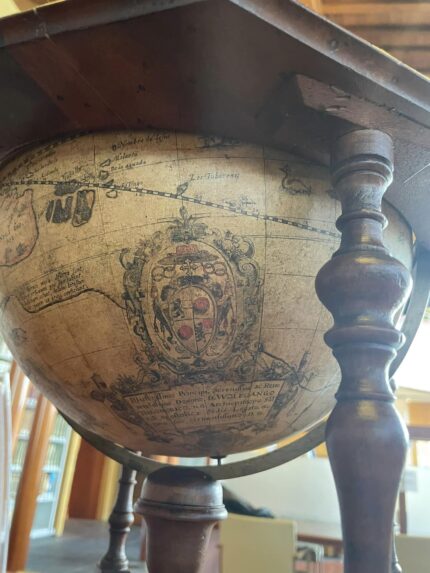

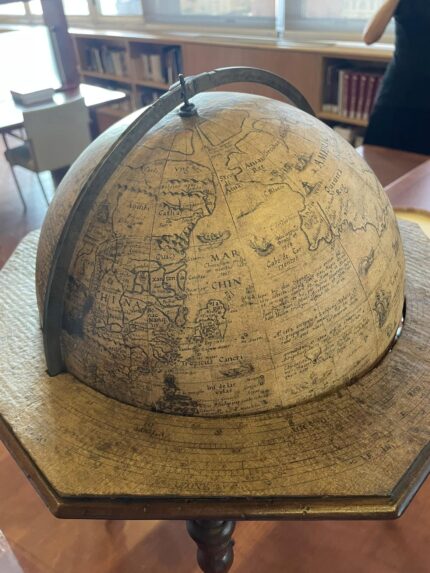

The terrestrial globe was made by Antwerp cartographer Cornelis De Jode in 1594. Most of his surviving oeuvre is a world atlas, the Speculum Orbis Terrae, he published in 1593. It sold terribly at the time, so today there are only a dozen or so copies known. Dedicated to Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg from 1587 until he was deposed, imprisoned and succeeded by his nephew in 1612, this globe is the only surviving globe by De Jode. It was previously known only from a series of cartographical sections now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Italy’s Ministry of Culture acquired the globe last November for €385,568 ($407,000) on behalf of the Regional Direction of Museums for Tuscany. It had been appeared on the market in 2016 but Italy placed an export ban on it due to its great rarity and historical significance.

It was in dire condition at the time of the sale. The printed paper surface of the globe was badly deteriorated, darked and with several gaps. Its condition was analyzed and assessed for its urgent conservation needs. The non-profit Friends of Florence foundation financed a delicate and complex intervention of cleaning and restoration by the Officina del Restauro in Florence.

The restored globe is now on permanent loan in the Museo Galileo where it will be on display alongside the museum’s important selection of terrestrial and celestial globes.