An 11th century Viking bronze die discovered by a metal detectorist in Norfolk earlier this year is going up for auction with a pre-sale estimate of £16,000–£24,000 ($21,000-$31,000). Its size, excellent condition and depth of the relief make it one of the finest examples of a Pressblech die found in England.

An 11th century Viking bronze die discovered by a metal detectorist in Norfolk earlier this year is going up for auction with a pre-sale estimate of £16,000–£24,000 ($21,000-$31,000). Its size, excellent condition and depth of the relief make it one of the finest examples of a Pressblech die found in England.

The thickness, sturdiness and high reliefs of these objects points to them having been used as dies to produce decorated foils quickly. The die would be placed on a hard surface (like an anvil) face-up, and metal foil put on top of the die. It would then be covered with a flexible buffer and hammered hard to push the foil deep into the relief and stamp the design on it. The gentle curve of the Norfolk die suggests the stamped foil was intended for a curved surface, the cheek guards of a Viking helmet, for example.

Jason Jones discovered the die in January while metal detecting in a field in Norfolk. He had scanned the site before and discovered two silver coins, so returned in the hopes of finding more. Just two inches under the surface, he found the bronze die instead. He didn’t know what it was or what age it might be until he posted a photo on Facebook and he was deluged with suggestions that it might be a Viking artifact. He called it in to the local finds liaison officer of the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Jason Jones discovered the die in January while metal detecting in a field in Norfolk. He had scanned the site before and discovered two silver coins, so returned in the hopes of finding more. Just two inches under the surface, he found the bronze die instead. He didn’t know what it was or what age it might be until he posted a photo on Facebook and he was deluged with suggestions that it might be a Viking artifact. He called it in to the local finds liaison officer of the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

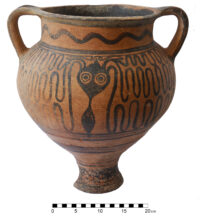

![]() It is 5.5 inches long and 1.27 inches wide at the rectangular end which then tapers to a pointed end. There is a slight curve to the die and the back is undecorated. The front is intricately carved with a high-relief design of two stylized animals, one larger that interlaces its body and tendrils, forming an open figure eight with the smaller creature at the base. The relief is bordered by a beaded ridge that runs about two thirds of the way down then flattens into a plain ridge. That angles inwards just before reaching the terminal and the ridges converge to form a fleur-de-lis that fills the pointed end.

It is 5.5 inches long and 1.27 inches wide at the rectangular end which then tapers to a pointed end. There is a slight curve to the die and the back is undecorated. The front is intricately carved with a high-relief design of two stylized animals, one larger that interlaces its body and tendrils, forming an open figure eight with the smaller creature at the base. The relief is bordered by a beaded ridge that runs about two thirds of the way down then flattens into a plain ridge. That angles inwards just before reaching the terminal and the ridges converge to form a fleur-de-lis that fills the pointed end.

The design motif may be a representation of the world tree Yggdrasill with the great serpent Nidhogg weaving around the tree. The smaller creature could represent the squirrel Ratatosk or one of the other serpents who called Yggdrasill home. The features of the enlaced animals — small heads, oval eyes, the open figure eight, the wide, flat ribbon-like bodies — are typical of the Urnes style. Urnes style decoration was produced between around 1030 and 1100 A.D.

The design motif may be a representation of the world tree Yggdrasill with the great serpent Nidhogg weaving around the tree. The smaller creature could represent the squirrel Ratatosk or one of the other serpents who called Yggdrasill home. The features of the enlaced animals — small heads, oval eyes, the open figure eight, the wide, flat ribbon-like bodies — are typical of the Urnes style. Urnes style decoration was produced between around 1030 and 1100 A.D.

The closest comparable example is an 11th century bronze plaque with a foliate animal relief in a hybrid of Urnes and Ringerike styles that was found in the Thames in the early 20th century and is now in the British Museum. The carving is cruder and it is 1.3 inches shorter that the Norfolk Urnes Die.