Ten years after their discovery, 2,000-year-old bamboo slips have been deciphered and published as the lost medical texts of pioneering physician Bian Que.

Ten years after their discovery, 2,000-year-old bamboo slips have been deciphered and published as the lost medical texts of pioneering physician Bian Que.

Among all the unearthed by archaeologists so far, the content is believed to be a set of ancient medical documents detailing China’s hitherto richest content, most complete theoretical system, and of the utmost theoretical and clinical value.

The documents have been compiled into eight medical books as a series of books named “Tianhui medical slips,” said the information office of the Sichuan provincial government during a press conference held on Thursday. All the materials, including images of the bamboo slips, editorial explanatory notes, and illustrations on the TCM meridian mannequin uncovered alongside the slips, are contained in the newly published books.

Born around 407 B.C., Bian Que is considered the father of traditional Chinese medicine. He is credited with having developed the meridian theory and the acupoints along its channels. His biographers recount legends about him, like a deity having given him the gift of being able to see through the body to diagnose illness and that he once accomplished a successful heart transplant between two living people. His works were widely studied by physicians of the Han dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D., 25 – 220 A.D.), but they were lost over the centuries.

Born around 407 B.C., Bian Que is considered the father of traditional Chinese medicine. He is credited with having developed the meridian theory and the acupoints along its channels. His biographers recount legends about him, like a deity having given him the gift of being able to see through the body to diagnose illness and that he once accomplished a successful heart transplant between two living people. His works were widely studied by physicians of the Han dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D., 25 – 220 A.D.), but they were lost over the centuries.

In 2012, a team of archaeologists from the Chengdu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and the Jingzhou Cultural Relics Protection Center Western excavated the site of planned subway construction in the Tianhui Town area of Chengu. They unearthed four Western Han Dynasty tombs, earthen pits with timber outer shells, containing large quantities of lacquered wood, ceramics, bronze and iron artifacts.

In 2012, a team of archaeologists from the Chengdu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and the Jingzhou Cultural Relics Protection Center Western excavated the site of planned subway construction in the Tianhui Town area of Chengu. They unearthed four Western Han Dynasty tombs, earthen pits with timber outer shells, containing large quantities of lacquered wood, ceramics, bronze and iron artifacts.

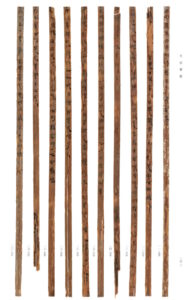

A group of almost 1,000 bamboo slips were found in Tomb No. 3. Submerged in the waterlogged tomb for 2,000 years, the slips were preserved but very soft and darkened. It took nearly a decade of work to clean, stabilize and restore the 930 bearing more than 20,000 characters to legibility.

The ancient Chinese writing system on the slips is complex to interpret. Pronunciation and lettering changed over the centuries, and names like Bian Que were written in several ways in Chinese (even more ways if you count different dialects). Archaeologists believed the slips were medical books of the Bian Que School thanks to repetition of certain key words and phrases known from his medical theory.

The ancient Chinese writing system on the slips is complex to interpret. Pronunciation and lettering changed over the centuries, and names like Bian Que were written in several ways in Chinese (even more ways if you count different dialects). Archaeologists believed the slips were medical books of the Bian Que School thanks to repetition of certain key words and phrases known from his medical theory.

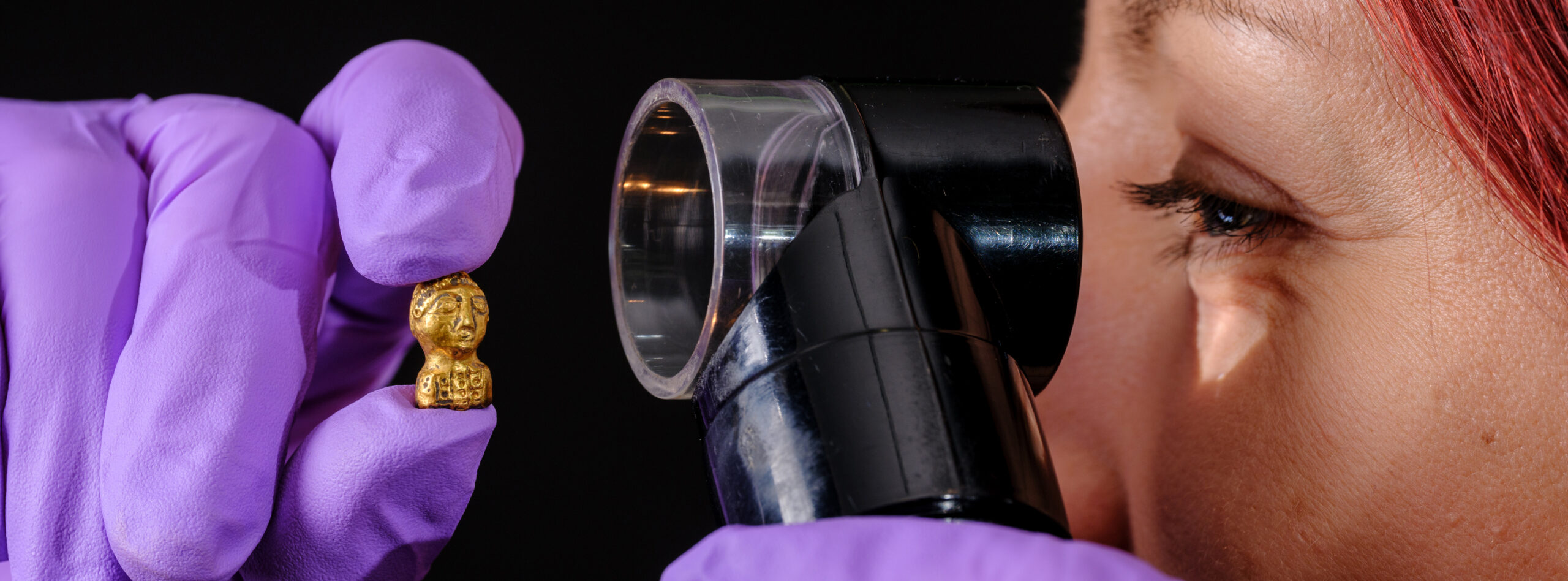

The hypothesis was strengthened with the discovery of an intact lacquered figurine of a person with the meridian lines and acupoints painted on in red and white. Major body parts — heart, lung, kidney — are labelled. It is the earliest and most complete human medical model of the meridians and acupoints ever found in China.