Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was copied by other artists and his students starting almost as soon as it was made in the first decades of the 16th century. Some of them have been advanced as Leonardo originals, at least in part (see the Isleworth Mona Lisa, for example), and others have always been known to be copies. One of these known copies is in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was copied by other artists and his students starting almost as soon as it was made in the first decades of the 16th century. Some of them have been advanced as Leonardo originals, at least in part (see the Isleworth Mona Lisa, for example), and others have always been known to be copies. One of these known copies is in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

Prado experts thought it was painted relatively early in the 16th century by an anonymous artist, but with its black painted background, bright red sleeves, and relatively flat shadowing compared to the velvety depth of da Vinci’s original, the Prado’s Mona Lisa didn’t get much attention. They also thought the wood was oak, which was used by northern European artists.

Last year curators took a closer look in anticipation of an upcoming loan to the Louvre. They found that the panel was actually walnut, a commonly used wood for oil paintings in 16th century Italy. Using infrared reflectography, they then found that underneath that dull black background was a beautiful Tuscan landscape almost identical to the one behind Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

IR also revealed the copy’s underdrawings, sketches that painters make before they start with the paint. The Louvre took IR images of the Mona Lisa in 2004. When the Prado curators compared the two sets of underdrawings, they found that they matched, suggesting that the copy was made contemporaneously with the original, following the changes to the composition as the master drew them before the final version was painted. There are documentary sources that attest to Leonardo having his students paint alongside him in the studio, but this is the first time we have IR evidence that strongly indicates contemporaneous painting.

IR also revealed the copy’s underdrawings, sketches that painters make before they start with the paint. The Louvre took IR images of the Mona Lisa in 2004. When the Prado curators compared the two sets of underdrawings, they found that they matched, suggesting that the copy was made contemporaneously with the original, following the changes to the composition as the master drew them before the final version was painted. There are documentary sources that attest to Leonardo having his students paint alongside him in the studio, but this is the first time we have IR evidence that strongly indicates contemporaneous painting.

Conservators have spent the past year removing the black overpaint — probably added in the 18th century to make it match other pieces with a black background in a gallery setting — and revealed the refreshed Mona Lisa copy in a presentation two weeks ago at London’s National Gallery.

The Prado’s technical specialist Ana González Mozo describes the Madrid replica as “a high quality work,” and in the paper she presented at the London conference, she provided evidence that the picture was done in Leonardo’s studio. The precise date of the original is uncertain, although the Louvre states it was between 1503 and 1506.

Bruno Mottin, the head conservator at the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, believes that the most likely painter of the Prado copy was one of Leonardo’s two favourite pupils.

Mottin proposes that it was either Andrea Salai, who originally joined Leonardo’s studio in 1490 and probably became his lover, or Francesco Melzi, who joined around 1506. If the Prado replica is eventually attributed to Melzi, it suggests a late date for the original.

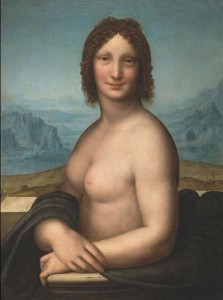

There is at least one other copy of Mona Lisa attributed to Salai and it doesn’t look as good as the Prado’s copy to my eye, although that could be the picture. He also painted Monna Vanna, a nude parody of Mona Lisa.

There is at least one other copy of Mona Lisa attributed to Salai and it doesn’t look as good as the Prado’s copy to my eye, although that could be the picture. He also painted Monna Vanna, a nude parody of Mona Lisa.

Salai’s reputation was more about his bad boy living than about the skill of his painting. Leonardo complained about Salai all the time in his notebooks, describing him as a “ladro, bugiardo, ostinato, ghiotto” (thief, liar, obstinate, glutton) whom Leonardo had to bail out of scrape after scrape. Still, he must have had something going for him since da Vinci lived with the youth from the time he was 10 years old until he was 35. Leonardo even left his enfant terrible property and paintings after his death in 1519, including the real Mona Lisa which Salai sold to King Francis I of France.

The Prado’s discovery might shed some light on details of the original. There are areas of the Prado Mona Lisa that are in much better condition than on the original — the spindles of the chair, for example, and the veil around her left arm — and Lisa herself looks considerably younger without that yellow cracked varnish that darkens and muddies her facial features in the original.

The copy is in the final stages of conservation. It will be displayed at the Prado in a few weeks, then it will go on loan to the Louvre for its exhibition with Leonardo’s Saint Anne (March 19 – June 25) where it will be back in the same room with Leonardo’s Mona Lisa for the first time in 500 years or so.

The “copy” is so much more beautiful than the “original”.

Thanks, Liv! The possible relationship of the Prado ML to the Louvre ML is now becoming a bit clearer. I had only seen the notice in the Guardian, which (as usual) was a mindless attack of incomprehensible discoveryitis.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/feb/01/new-mona-lisa-prado?newsfeed=true

Is it ultimately possible, I wonder, to deduce from technical evidence whether two painters were standing side-by-side executing the same subject, with the student revising the composition along with the master? It is certainly an intriguing concept (and maybe Leonardo’s idea of a cheap date?)

I’m sure the original looked as good if not better when it was first painted, but I agree with RW, the copy is much more vibrant and detailed. If only conservators could do some work to the original to make it stand out like the copy. Perhaps there is a copy of The Last Supper out there that proves Dan Brown’s theories… yeah, right. 😆

I agree! Congratulations to the Prado. The copy is so clear and the famous smile almost as mysterious.

We all want a piece of Mona Lisa…

Man. Rule 34 goes back much further than I would have thought.

Hey!! fix it quick!! there’s a “666” in lower left prado mona lisa…. oy vey gevalt!!… don’t let the dan brown crew get to it!!

It’s about time they clean up that old dirty version of the Mona Lisa.!

Why is the Louvre’s the original and the Prado’s the copy? What if both were painted by Leonardo and his assistants?

I am curious as well. how can one be sure if they were painted side by side in the exact same manner and sequence?

One can’t be sure. Attribution is always a tricky matter, and there have been many debates over the years over whether a given copy might be the REAL Mona Lisa, or at least been made in part by Leonardo himself. I don’t think we’ll ever know if Leonardo crossed the room and daubed some paint on the Prado’s version. The reason the original is still deemed the original is the skill in details, particularly the depth and richness of the sfumato shadows on her neck and face, as well as its long ownership history that traces its movements fairly cleanly from Leonardo to the French national collection.

whose is whose? i like the one on the left… the darker one… the other one is prettier… but mona looks sillier… like she could be selling something… but the one on the left… the darker one… well it looks like a woman… the eyes have a depth that the other is lacking and the painting technically has a quality of light and dark…

That’s the original Mona Lisa. I agree with you. 🙂

This painting is extremely important, but it puzzles me why it has not gotten due recognition years ago.

The colors in her garments prove that she is a member of the powerful Italian Sforza-Visconti dynasty. Leonardo was a court painter for the Milanese noble house for over 17 years. The long veil she is wearing is worn ONLY and specifically by the Milanese duchesses in mourning. There were only 4 Duchesses before the French overthrew the Milanese. Three were blond. Her identity is without dispute: Isabella of Aragon, daughter of King Alfonso II, and the young widow of Gian Galeazzo II Maria Sforza.

see kleio.org

If the sitter in the painting was really Salai or Leonardo in drag, why did not the French King, who became the owner of the painting and knew Leonardo’s face, make this conclusion? Why would he even want to own such a rediculous painting. Leonardo had just been aquitted of sodomy, why then would he paint himself in a dress? These assumptions were only started during the 19th century, and are thought to be politically correct facts in the 21st century.

The mystery was solved 10 yrs ago, by historian and author Maike Vogt-Luerssen. It is time to stop the lies of the world’s most famous painting.

to learn more of Leonardo’s EPIC life, based in 100’s of historical facts and visual evidences left in the paintings of his closest contemporaries see the above website and follow the facebook page.

Why would Leonardo arrange to have a copy made simultaneously with the original? The answer might be found in the article, “Leonardo’s Val di Chiana Map in the Mona Lisa”, in the peer-reviewed journal, Cartographica, 46:3, 2011, found at http://digital.utpjournals.com/issue/43517/7 .

If two copies were aligned, the image from one edge would continue onto the other, forming a newly reconstituted landscape that would match an actual place, namely the Val di Chiana, as mapped by Leonardo. The Prado investigators claim that it seems quite likely that Leonardo indeed had at least two such copies – theirs being one of them. The Val di Chiana map was completed just before Leonardo started to paint the Mona Lisa. So it is more than likely that the two copies and the map were present, simultaneously, in his workshop.

Two such juxtaposed copies would also form a stereoscopic arrangement. This would be a painterly example of what Leonardo was discussing in his Notebooks under “Differences of perception of one eye and both eyes”. The Mona Lisa and copy could be part of Leonardo’s investigations in stereopsis.

Is that “666” in the lower left hand corner for real?

Has it always been there, or is it someone’s idea of a joke?

Does anyone know when the painting was defaced with this “666”?

I don’t actually see a 666 on the canvas. Do you? I thought that was a joke.

I wonder why you say that Salai sold the Mona Lisa to Francois I, when the well-known and oft-mentioned work of Sironi and Shell in the early 1990’s established that Salai still had the Mona Lisa and several other Leonardos in his possession when he died. Maybe his sisters, who divided Salai’s belongings between them, sold the painting to Francois?

The 666 (when you click on the image it enlarges and the number is easier to notice) is probably just the museum catalog number. If it was there from the beginning it seems like it would be pretty easy to attribute the painting to Salai, since his nickname meant “little devil” or “little Satan” yet even with the probable date pointing to Salai they are still making up their minds.

There are many secrets hidden in Mona Lisa picture and many other pictures of that era. For example there are many pictures of Albrecht Durer where there are many secret codes are hidden. You can check these articles about the paintings here http://www.albrechtdurerblog.com/.

Please stop using any pretext to spam your blog. At the very least you could make the minimum effort required to write something that indicates you troubled yourself to actually read the blog entries here.

There are many ‘repeat’ paintings within the da Vinci circle of artist. Da Vinci worked for the royal Sforza’s in Milan for over 16 years. His job was the paint the royal members. He started the Da Vinci Academy during this time with many students and fellow contemporaries came to study under him.

Historian of the Renaissance, Maike Vogt-Luerssen tells us that these multiple paintings were made to give to royal family members of other noble houses. History records noble houses as containing at least one room that was full of paintings.

Don’t be fooled, there are many years missing out of Davinci’s life on purpose. You have to find them in other historical sources and in understanding the knowledge of the traditions of the paintings in which were left clues.

Da Vinci sucessfully obscured “Mona Lisa’s” identity of necessity to protect those to whom it would affect the most. The real story is fascinating, true to real human existance, and worthy of DaVinci’s genius and calibur! He was really was a true genius, and has kept the world guessing for 500 years, while the truth stares us in the face. How cool is that?! Amazing!

I have a small version of the (6×4 inches) Prado Mona Lisa copy that I bought at a thrift store … from the yellowing of the sticker on the back that says Espana a decorative craft hand made in Spain it looks like it’s probably 40 years old or older. I’m wondering if it is a souvenir from the Prado Museum? . I was surprised to see the “discovery” of this painting when they at sometime in the past were making souvenir copies of it? This also has the 666 in the lower left hand corner ….I always thought it was strange that it looked so much like Mona Lisa but with a black background…..does anyone know if the museum would have sold copies of this?

MAGDALENA SOEST: “LEONARDO’S MONA LISA IS A PORTRAIT OF CATERINA SFORZA”

Magdalena Soest’s sensational identification of the Mona Lisa as Caterina Sforza was first published in 2002. It is based solely upon the discoveries and findings made by the author herself. Let me tell you a very few examples:

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa possesses a striking physiognomic correspondence with an older(!) portrait, with the portrait of Caterina Sforza painted by Lorenzo di Credi (ca 1485);

in the embroidery and the folds of the garment, in the hairstyle and the landscape of the Mona Lisa there are emblems of the Sforza (lily, serpent) and the Medici (lily, oval, interwoven rings) represented – the dynasties to which Caterina, through birth and marriage, belonged to and identified with (she was the daughter of Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza of Milan, and the widow of Giovanni de’ Medici);

a Milanese archive document of 1525 (a solicitor’s document in a legal battle concerned with the inheritance of Leonardo’s student Salai) contains a short description of the Mona Lisa and calls the portrait “Quadro dicto la honda. C.”: “Portrait of the worthy C.” –

etc., etc..

Magdalena Soest demonstrates that Caterina Sforza satisfies the necessary artistic and historical conditions to having been the Mona Lisa model, and supplies additional proofs to justify this claim. Soest’s thesis itself, and all her discoveries, findindings, and analyses are revolutionary and new. Besides, never before had Caterina Sforza been associated with the Mona Lisa, or even hinted at.

REGARDING MONA LISA’S IDENTITY AND ISABELLA OF ARAGON

In 1979 Robert Payne identified the “Mona Lisa” as a portrait of Isabella of Aragon / Isabella d’Aragona (see his book: ‘Leonardo’); Payne’s theory was repeated by Maike Vogt-Luerssen in 2003 (see her book: ‘Wer ist Mona Lisa? Auf der Suche nach ihrer Identität’).

To tell the truth, I don’t like the said theory, it’s completely incongruous. Be that as it may – Payne’s authorship is unquestionable.

It’s amazing to see how people have always been interested in the Mona Lisa. A few weeks ago I saw the exhibition Da Vinci The genius in Brussels. There the secrets of the Mona Lisa were unraveled. It was the most crowded room of the whole exhibition. I’ve seen the real painting at the Louvre in Paris and I’ve read a lot about her, but she remains to astonish me. Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is the most beautiful painting from the Renaissance!

I’d assume this is partially due to the restoration work done on the copy, which the original was not allowed to undergo.

You would be correct in that assumption.

this website is so boring i mean dang do better godlee

Just returned to this after a couple of years. The colours of the cleaned Prado copy are a stunning revelation. One knew that something like this has to be under the Louvre’s coats of varnish, but to see it, without the howls and controversy that would accompany any attempt to clean the original, is wonderful. Some works of art are so important (the currently sickeningly over-used catch-word “iconic” can very rightly be applied here) that any attempt to “restore” them, except to halt demonstrable deterioration, should be left to future generations with techniques yet to be devised.

They can’t do work to the original. It was tried before but old Leo did a lot of glazing which they found to come off with the old varnish. What you see is what you get as Leo liked to experiment a little too much and wasn’t concerned about things lasting.

The Prado copy seems to have better perspective also.

Whomever “restored” the other Mona should have left the background darker as now, it distracts from the woman — just my opinion