An exceedingly rare French Gothic ivory casket carved with low relief scenes of Arthurian romance is at risk of leaving the UK if a museum or gallery cannot be found to acquire it for the assessed price of £1,506,000. The UK’s Arts Minister has placed a temporary export bar on the object to give local institutions the opportunity to raise the sum by March 1, 2023.

An exceedingly rare French Gothic ivory casket carved with low relief scenes of Arthurian romance is at risk of leaving the UK if a museum or gallery cannot be found to acquire it for the assessed price of £1,506,000. The UK’s Arts Minister has placed a temporary export bar on the object to give local institutions the opportunity to raise the sum by March 1, 2023.

The casket sold at Edinburgh’s Lyon & Turnbull auction house in May 2021 for £1,455,000, a world record for a medieval ivory casket and the highest price any single object has ever sold for at an auction in Scotland. It is one of only nine of secular Gothic ivory coffrets known to survive, and almost all of them are in museums like the Louvre and the Metropolitan.

[Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest] member Stuart Lochhead said:

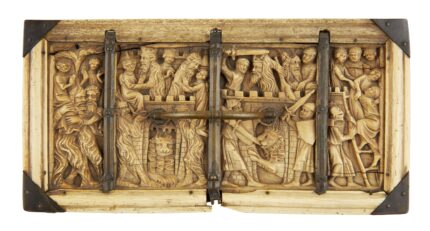

This French 14th-century carved ivory casket is adorned with scenes of chivalry and romance including depictions of wild men – ranging from the rescue of a lady from one such assailant to a procession of knights and ladies who lead the captured wild men in chains. Similar iconography exists on some of the other nine known mediaeval caskets of this type, but it is the present one that illustrates some of the earliest and rarest type of images.

No disrespect to the honorable members of the RCEWA, but while they’re right about the wild men being particularly awesome on this example, I’m not sure that the scene on the top of the casket depicts the wild men attacking the Castle of Love. The usual iconography of the Castle of Love, a chivalric metaphor for seduction, is women arrayed along the crenellations while fully human knights launch catapults full of roses and scale the walls to breach the ladies’ “defenses.” The wild men on this coffer are both fighting knights defending the castle and kidnapping women (rather gently, really, almost like they’re saving them from the knights). Two lions guard two gates at the bottom of the castle. This strongly suggests it’s the Grail Castle of Corbenic, the home of the Holy Grail according to the 13th century French prose romance L’Estoire del Saint Graal, so this is likely the culmination of Galahad’s Grail quest only with a bunch of wild men in the melee.

The Grail makes a starring appearance on the right side panel. A kneeling angel holds it aloft before the arrayed Arthurian knights. Galahad, holding the magical sword he pulled from the stone, is in the center. Scenes from another Arthurian romance, the legend of Tristan and Isolde, on the left side panel and on the left two sections of the back panel.

The Grail makes a starring appearance on the right side panel. A kneeling angel holds it aloft before the arrayed Arthurian knights. Galahad, holding the magical sword he pulled from the stone, is in the center. Scenes from another Arthurian romance, the legend of Tristan and Isolde, on the left side panel and on the left two sections of the back panel.

Elephant ivory imported from Africa and Asia had been prized since antiquity for its lustrous, flesh-like glow and carvable surface. In medieval northern Europe, it was a luxury material reserved largely for religious objects (book covers, statuettes, reliquaries, croziers). Ivory supplies plummeted in the 12th century, only picking back up in the mid-13th century when Mediterranean merchants established a new water-going route through Gibraltar direct to the English Channel for the textile dye and ivory trade.

By the turn of the 14th century, the higher availability of ivory had lowered the price enough that a material once exclusive to liturgical use was now available for personal objects like mirrors, combs, cosmetics vessels and coffers. Instead of religious subjects, these objects were carved with secular motifs popular among the aristocratic buyers of such high-end toiletry items — courtly love, Arthurian romance, falconry, capturing a unicorn. The caskets are believed to have been romantic gifts used to store love tokens, letters, jewels, etc. We know in one specific case, that of Clemence of Hungary, Queen of France for less than a year between 1315 and 1316, that her carved ivory box contained a comb and mirror set and a chess set.

By the turn of the 14th century, the higher availability of ivory had lowered the price enough that a material once exclusive to liturgical use was now available for personal objects like mirrors, combs, cosmetics vessels and coffers. Instead of religious subjects, these objects were carved with secular motifs popular among the aristocratic buyers of such high-end toiletry items — courtly love, Arthurian romance, falconry, capturing a unicorn. The caskets are believed to have been romantic gifts used to store love tokens, letters, jewels, etc. We know in one specific case, that of Clemence of Hungary, Queen of France for less than a year between 1315 and 1316, that her carved ivory box contained a comb and mirror set and a chess set.

Gothic ivory carving reached its apex between 1230 and 1380 and Paris was the center of production with other capitals following the fashions and trends established there. The style of carving and manufacture indicates the Edinburgh coffret was made in a workshop in Paris around 1330. By the end of the 14th century, plague, war and economic upheaval had throttled the ivory supply and carved objects became more scarce again.

One of the other rare features of this casket is its long ownership history. It can be traced directly to the early 17th century. A genealogy of the Baird family of Auchmeddan Castle in Aberdeen records the chest in the possession of Thomas Baird, Fransciscan friar of a monastery in Besançon, France, some time after 1609. It remained in the Baird family, passing to descendants by marriage. One of those descendants was the seller who put it up for auction last year, so the casket has been in Scotland for 400 years. That was one of the factors in the Committee’s decision to recommend the export ban.