Robert and Betty Fooks were already living a history nerd’s dream when they bought a 17th century Dorset farmhouse fixer upper in 2019. That escalated into full-on history nerd fantasyland when Robert took a pickaxe to the floor of their kitchen and discovered 1,029 gold and silver coins from the English Civil War (1642-1644).

Robert and Betty Fooks were already living a history nerd’s dream when they bought a 17th century Dorset farmhouse fixer upper in 2019. That escalated into full-on history nerd fantasyland when Robert took a pickaxe to the floor of their kitchen and discovered 1,029 gold and silver coins from the English Civil War (1642-1644).

South Poorton Farm in a small West Dorset hamlet was 400 years old when the Fooks’ bought it and in need of extensive renovation. They decided to remove the modern concrete floor to create more head space and ultimately dug down through almost two feet, passing through old flagstones and bare earth. Robert was putting in some sweat equity one October evening, digging up a bare earth area with his pickaxe when he encountered a glazed pottery bowl full of coins. The bowl was smashed, either by the pickaxe or earlier, but the coins were unscathed.

South Poorton Farm in a small West Dorset hamlet was 400 years old when the Fooks’ bought it and in need of extensive renovation. They decided to remove the modern concrete floor to create more head space and ultimately dug down through almost two feet, passing through old flagstones and bare earth. Robert was putting in some sweat equity one October evening, digging up a bare earth area with his pickaxe when he encountered a glazed pottery bowl full of coins. The bowl was smashed, either by the pickaxe or earlier, but the coins were unscathed.

The discovery was reported to the local Finds Liaison Officer and the hoard was transferred to the British Museum for cleaning, documentation and valuation. The hoard contains gold coins, silver half crowns, shillings and sixpences of James I and Charles I, and silver shillings and sixpences of Elizabeth I, Phillip and Mary. They were deposited in a single event between 1642 and 1644, the early years of the First English Civil War.

The discovery was reported to the local Finds Liaison Officer and the hoard was transferred to the British Museum for cleaning, documentation and valuation. The hoard contains gold coins, silver half crowns, shillings and sixpences of James I and Charles I, and silver shillings and sixpences of Elizabeth I, Phillip and Mary. They were deposited in a single event between 1642 and 1644, the early years of the First English Civil War.

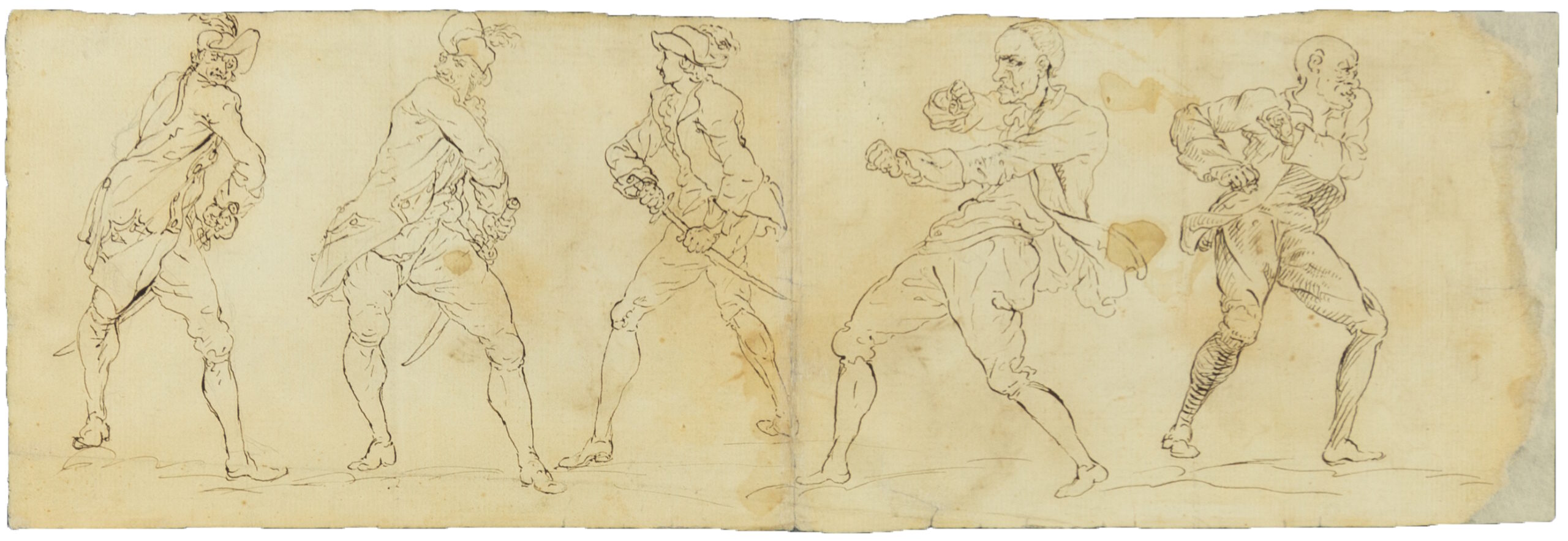

Dorset, its arsenals and its ports were taken by Parliament when war broke out in August 1642, but Royalist troops regained a lot of that ground in 1643. Parliament still controlled the ports. While no major battles took place in the county, there was plenty of troop movement on both sides, lots of requisitioning of supplies, sieges, clashes, towns getting burned, just general wartorn misery all around. The kind of turbulence that leads people to put their life savings in a pot and bury it under the floor.

The hoard is a older than 300 years, contains precious metal and is a grouping of multiple coins, it fits the definition of official Treasure. Typically this type of find would end up property of the Crown and a local museum would be given the opportunity to acquire it for the price of the assessed valuation. No museum must have wanted it or been able to raise the cash, because the hoard was returned to the finders and the couple put the hoard up for auction at Duke’s Auctioneers in Dorchester. The total pre-sale estimate for was £35,000. The auction took place on April 23rd, and all together, the coins sold for £60,740. A 1636 Charles I Gold Unite Crown was the biggest seller going for £5,000. A 1627 Charles I Gold Unite took second place with £3,800. The oldest coins, a lot of three Philip and Mary silver shillings from around 1554-1558, sold for £240.

The hoard is a older than 300 years, contains precious metal and is a grouping of multiple coins, it fits the definition of official Treasure. Typically this type of find would end up property of the Crown and a local museum would be given the opportunity to acquire it for the price of the assessed valuation. No museum must have wanted it or been able to raise the cash, because the hoard was returned to the finders and the couple put the hoard up for auction at Duke’s Auctioneers in Dorchester. The total pre-sale estimate for was £35,000. The auction took place on April 23rd, and all together, the coins sold for £60,740. A 1636 Charles I Gold Unite Crown was the biggest seller going for £5,000. A 1627 Charles I Gold Unite took second place with £3,800. The oldest coins, a lot of three Philip and Mary silver shillings from around 1554-1558, sold for £240.