Archaeologists digging on the banks of the River Usk near the Roman fortress of Caerleon in South Wales have uncovered the remains of what is only the second Roman port ever found in Britain. The other is in London, and it was a commercial port that appears to have gone up haphazardly over time as individual merchants built docks for their own needs. The Caerleon port is a single structure, most likely built to supply and move the legions stationed at the fortress.

Archaeologists digging on the banks of the River Usk near the Roman fortress of Caerleon in South Wales have uncovered the remains of what is only the second Roman port ever found in Britain. The other is in London, and it was a commercial port that appears to have gone up haphazardly over time as individual merchants built docks for their own needs. The Caerleon port is a single structure, most likely built to supply and move the legions stationed at the fortress.

The Cardiff University team has found in relatively good condition the main quay wall, jetties, landing stages and docking wharves next to a group of several Roman buildings they discovered in a dig last year.

“We are excavating the remains of a previously unknown complex of important Roman buildings that survive remarkably well considering how long they have lain underground.

“The port or harbour is a major addition to the archaeology of Roman Britain and adds a new dimension to our understanding of Caerleon as we can start to think about how the river connected the fortress and Wales to the rest of the Roman Empire.

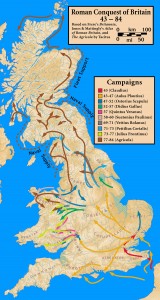

“We believe that the port dates to period when the Legions were fighting and subduing the native tribes in western Britain and it’s incredible to think that this is the place where the men who took part in the conquest would have arrived.

“Our trenches are also looking at several buildings adjacent to the port and we have also found rooms with under floor heating systems, collapsed walls and roofs, as well as many thousands of objects made, used and lost during the Roman period.

The fortress was built in 74-75 A.D. during the final push under Julius Frontinus to quell the feisty local tribe, the Silures. Claudius’ troops first invaded in 43 A.D., remember, so the Welsh had been giving Rome the pointy end for 30 years by the time the r Legio II Augusta quartered permanently at Caerleon. Historians previously thought that Roman troops had built their own roads then walked them to Wales, but the discovery of the port suggests that the front lines against the Silures were supplied far more promptly and safely by river.

The fortress was built in 74-75 A.D. during the final push under Julius Frontinus to quell the feisty local tribe, the Silures. Claudius’ troops first invaded in 43 A.D., remember, so the Welsh had been giving Rome the pointy end for 30 years by the time the r Legio II Augusta quartered permanently at Caerleon. Historians previously thought that Roman troops had built their own roads then walked them to Wales, but the discovery of the port suggests that the front lines against the Silures were supplied far more promptly and safely by river.

During the four years that Julius Frontinus was governor of Britain (74-78 A.D.), he not only built the fortress of Caerleon and, presumably, its port, but he also established a series of smaller forts 10 or so miles away from each other to house auxiliary troops. This network would have relied on the headquarters for supplies, so all the more use for a functional water route.

In what is probably a coincidence but a cool one, Frontinus is most famous today as the author of De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae, a comprehensive two-volume report of the aqueducts of Rome written when he was appointed Water Commissioner by emperor Nerva in 95 A.D. It’s incredibly nerdy. He lists every aqueduct, its history, size, condition, discharge rates, water quality and source. He mapped the entire water system, set up regular maintenance to prevent leaks and ensure clean and even delivery, and he tracked down and eliminated an enormous number of illegal taps on the lines where local landowners and merchants had connected their own pipes to the main channel to divert water for their selfish needs.

The Guardian has an excellent digital rendering of the port and fortress that it won’t let me embed because it’s mean.