A rare ceremonial yew-wood club given to Captain James Cook by the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Vancouver Island in 1778 during his third and final voyage has returned to Canada for good. Philanthropist Michael Audain donated it to the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology (MOA) where it was unveiled Tuesday. It was the last Canadian artifact from Cook’s personal collection still in private hands. They’re all in museums in London, Vienna and Berlin, so believe it or not, this is the only Cook artifact from Cook’s voyage to Canada actually in Canada. This is the first time it’s been home since Cook took it with him on his way back to Hawaii 234 years ago.

A rare ceremonial yew-wood club given to Captain James Cook by the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Vancouver Island in 1778 during his third and final voyage has returned to Canada for good. Philanthropist Michael Audain donated it to the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology (MOA) where it was unveiled Tuesday. It was the last Canadian artifact from Cook’s personal collection still in private hands. They’re all in museums in London, Vienna and Berlin, so believe it or not, this is the only Cook artifact from Cook’s voyage to Canada actually in Canada. This is the first time it’s been home since Cook took it with him on his way back to Hawaii 234 years ago.

The artifact, a club in the shape of an arm and hand holding a sphere, was carved with stone tools or possibly mussel shells years before it was given to Captain Cook, probably around the mid-1700s. That puts it in the last generation of First Nations objects made before contact with Europeans. It is the oldest known club of its kind, and it’s the most finely executed. A symbolic mark of high status for whoever owned it, the club might also have been used as a weapon, although it’s in excellent condition so if it saw action it didn’t see much.

Cook’s third voyage of exploration on his trusty ship, HMS Resolution, took him from Plymouth around the Cape of Good Hope to New Zealand to Hawaii (1776–1777). He left Hawaii for parts north seeking the elusive Northwest Passage, landing at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island on March 28, 1778. Cook stayed in a Nootka Sound cove now called Resolution Cove for less than a month, trading with the Nuu-chah-nulth village in Yuquot. The Nuu-chah-nulth were cordial, but they drove a hard bargain, turning up their noses at the low value trinkets Cook was accustomed to fobbing off on First Nations he encountered during his voyages. In exchange for mast timber and the sea otter pelts Cook wanted, the Yuquot villagers wanted metal, and the quality of the metals he offered — lead, pewter and tin — left something to be desired.

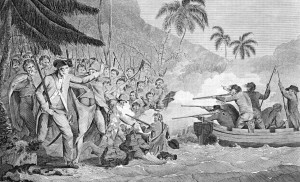

On April 26th, Cook shipped out, heading north again. He mapped most of the northwest coast of North America on his way to the Bering Strait. He tried to navigate the strait several times but found it impassable. He turned around and headed back to Hawaii where on Valentine’s Day, 1779 tensions with the Hawaiians would erupt over the matter of a stolen boat. When Cook and his men attempted to take King Kalaniʻōpuʻu hostage to exchange him for the stolen boat, they were rebuffed by the King’s men. Cook was hit on the head and stabbed during the ensuing fracas and died.

On April 26th, Cook shipped out, heading north again. He mapped most of the northwest coast of North America on his way to the Bering Strait. He tried to navigate the strait several times but found it impassable. He turned around and headed back to Hawaii where on Valentine’s Day, 1779 tensions with the Hawaiians would erupt over the matter of a stolen boat. When Cook and his men attempted to take King Kalaniʻōpuʻu hostage to exchange him for the stolen boat, they were rebuffed by the King’s men. Cook was hit on the head and stabbed during the ensuing fracas and died.

His crew initially tried to complete the voyage, heading back to the Bering Strait. When Charles Clerke, the commander of the second main ship (HMS Discovery) died, they gave up the Northwest Passage and turned back for home. They finally got back in October of 1780.

Cook’s personal collection of objects acquired on his final voyage, including the club from Vancouver, was given to his widow Elizabeth. His family gave it to the Leverian Museum in London where it was on display along with other artifacts from Cook’s voyages. It was sold to a private buyer in 1806 and passed through another museum and various private hands for the next two centuries. In 1967 it made its way to New York, where last year Canadian dealer Donald Ellis bought it from the $40 million estate of antique dealer George Terasaki.

Well aware that there were no Cook artifacts in Canada, Ellis contacted Michael Audain, whose foundation has repatriated several important First Nations artifacts to Canada, offering him first crack at this unique and significant piece of Canadian history. Audain paid $827,000 for the club — its market value is an estimated $1.2 million — and donated it to the MOA.