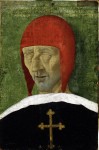

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (reigned 1493-1519) never actually had a triumphal procession. What he did have was a discerning eye for self-aggrandizing propaganda, and he enlisted artists to ensure the image of the great emperor, son of emperors, glorious in victory, bringer of prosperity and high culture to his people, would capture the grandeur of his reign and long outlive the man.

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (reigned 1493-1519) never actually had a triumphal procession. What he did have was a discerning eye for self-aggrandizing propaganda, and he enlisted artists to ensure the image of the great emperor, son of emperors, glorious in victory, bringer of prosperity and high culture to his people, would capture the grandeur of his reign and long outlive the man.

As one often sees today with midlife crisis Lamborghini purchases, Maximilian was overcompensating. His father Frederick III became the first Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor in 1452. Maximilian co-ruled the empire with his father for the last 10 years of his reign (1483-1493). With so fresh a link to the imperial throne, Maximilian made a point of emphasizing royal connections, real or fictional, in his family line. He traced his ancestry back to Hector, son of King Priam of Troy, Julius Caesar, King Arthur, Charlemagne and a number of saints. The point of this family tree liberally sprinkled with myth was to underscore that though the Habsburg dynasty might be technically brand spanking new to the throne, its long history of heroism, military genius, leadership, chivalric ideals and piety made it even more of an imperial line than some of the other families with royal claims.

As one also sees today with those midlife crisis Lamborghini purchasers, Maximilian’s mortality weighed heavily upon him. From 1514 on, he carried his coffin with him wherever he traveled, and he traveled a lot. To ensure that his legacy would live on once he was gone, he spent a great deal of money to immortalize his deeds, words and lineage. When questioned on the vast sums he dispensed on this pursuit, Maximilian replied:

“He who does not provide for his memory while he lives, will not be remembered after his death, so that this person will be forgotten when the bell tolls. And hence the money I spend for my memory will not be lost.”

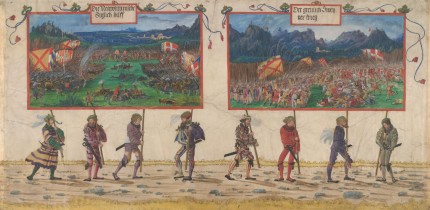

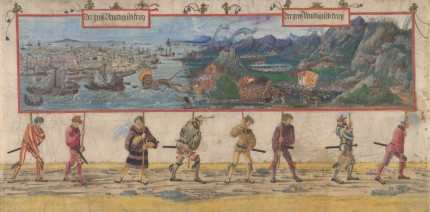

With his historical legitimacy and posthumous legacy in mind, in the last decade of his life the emperor commissioned three monumental works inspired by the victorious generals of Rome: the Triumphal Procession, the Great Triumphal Chariot, and the Triumphal Arch. Engraver Hans Burgkmair began work on the Triumphal Procession in 1512, designing scenes from the life and military victories of Maximilian carried along in a long procession of musicians, hunters, falconers, standard bearers, courtiers, exotic baggage trains, Habsburg ancestors, knights and a hugely elaborate imperial carriage. The original gouache was painted by Albrecht Altdorfer on 109 large vellum sheets which all together were more than 100 meters (328 feet) long.

Behold the glory (click for large versions to truly behold the glory):

The detail is not only beautiful, but has also proven an invaluable resource for historians of the musical instruments, heraldry, clothing and armor of the period. My favorite part is the Lion of St. Mark turning tail and running from Maximilian’s forces in The Great Venetian War. By 1517, the emperor would lose all the territory he had won in that particular skirmish.

We don’t know how this monster piece was displayed, but some art historians believe it was unrolled and moved forward while the seated emperor watched, a Renaissance animated gif, if you will. We do know that he disseminated this tribute to his military successes and illustrious ancestry to the populace via reproduction prints made from woodcuts engraved by Burgkmair, Altdorfer and the greatest master of them all, Albrecht Dürer.

Albrecht Dürer also created the Triumphal Arch and the Great Triumphal Chariot, only the former of which was completed before Maximilian’s death. The woodcuts of the Triumphal Procession and of the Triumphal Arch, which ended up being composed of 192 woodcut panels for a total dimension of 9′ 8″ by 11′ 8 1/2″, were the largest woodcut prints ever produced. They were intended to be plastered to walls, like giant billboards advertising the awesomeness of the emperor, and to be issued in large special edition publications.

Albrecht Dürer also created the Triumphal Arch and the Great Triumphal Chariot, only the former of which was completed before Maximilian’s death. The woodcuts of the Triumphal Procession and of the Triumphal Arch, which ended up being composed of 192 woodcut panels for a total dimension of 9′ 8″ by 11′ 8 1/2″, were the largest woodcut prints ever produced. They were intended to be plastered to walls, like giant billboards advertising the awesomeness of the emperor, and to be issued in large special edition publications.

Half of the original vellum Triumphal Procession sheets are now gone, but sheets 49 through 109 have survived and are part of the permanent collection of the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Austria, which also has many of the original woodcuts used to make the reproduction prints. They remain in good condition, with the colors and details still brilliant. They are very rarely seen, however, and were last put on public display in 1959 in celebration of Maximilian’s 500th birthday.

Now is your chance to see all 54 meters (177 feet) remaining of the original Triumphal Procession painting. The Albertina has put the complete Triumphal Procession sheets on display along with many other related masterpieces in a new exhibit: Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Dürer.

On his deathbed in 1519 Maximilian fled from all this splendor he had purchased. Terrified of God’s judgment on his prideful life, after receiving the last rites he abdicated all his titles and ordered that his body be mutilated after death. His hair was to be shorn, his teeth broken off and his back scourged. He was buried in a simple tomb in St. George’s Cathedral in the castle of Wiener Neustadt, northeast Austria, where he was born. Forty years later, his grandson Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I would build a church (the Hofkirche) with an elaborate cenotaph in Innsbruck in Maximilian’s memory.

On his deathbed in 1519 Maximilian fled from all this splendor he had purchased. Terrified of God’s judgment on his prideful life, after receiving the last rites he abdicated all his titles and ordered that his body be mutilated after death. His hair was to be shorn, his teeth broken off and his back scourged. He was buried in a simple tomb in St. George’s Cathedral in the castle of Wiener Neustadt, northeast Austria, where he was born. Forty years later, his grandson Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I would build a church (the Hofkirche) with an elaborate cenotaph in Innsbruck in Maximilian’s memory.

Despite the last-minute foray into mortification, Maximilian’s political, military and dynastic efforts during his life secured for the Habsburg family centuries of power among the crowned heads of Europe. The range of history set in motion by Maximilian’s choices is breathtaking. His marriage to Mary of Burgundy ultimately netted much of what are today the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and a considerable piece of northern France for the Habsburg line. His son’s marriage to Joan of Castile (later known as Juana la Loca, Joan the Crazy Lady, for among other things allegedly carrying her husband’s corpse with her wherever she went for years after he died of typhoid fever) resulted in their son Charles V becoming King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor at the same time.

Despite the last-minute foray into mortification, Maximilian’s political, military and dynastic efforts during his life secured for the Habsburg family centuries of power among the crowned heads of Europe. The range of history set in motion by Maximilian’s choices is breathtaking. His marriage to Mary of Burgundy ultimately netted much of what are today the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and a considerable piece of northern France for the Habsburg line. His son’s marriage to Joan of Castile (later known as Juana la Loca, Joan the Crazy Lady, for among other things allegedly carrying her husband’s corpse with her wherever she went for years after he died of typhoid fever) resulted in their son Charles V becoming King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor at the same time.

It was Charles V who sacked Rome in 1527 and imprisoned the Pope, preventing him from granting Britain’s King Henry VIII an annulment of his marriage to his wife and Charles’ aunt, Catherine of Aragon. Charles’ son, Maximilian’s great-grandson, would become King Philip II of Spain, King of England during his marriage to Queen Mary I, and sender of the Spanish Armada so soundly defeated by the navy of Queen Elizabeth I, the weather, and the violent moods of the English Channel. The Spanish Habsburg line died in 1700 with poor Charles II who was riddled with congenital deformities and diseases thanks to the family’s penchant for uncle-niece and cousin-cousin marriages, but the Austrian Habsburgs reigned until the 1780 death of the formidable Queen Maria Theresa, mother of Queen Marie Antoinette of France.

It was Charles V who sacked Rome in 1527 and imprisoned the Pope, preventing him from granting Britain’s King Henry VIII an annulment of his marriage to his wife and Charles’ aunt, Catherine of Aragon. Charles’ son, Maximilian’s great-grandson, would become King Philip II of Spain, King of England during his marriage to Queen Mary I, and sender of the Spanish Armada so soundly defeated by the navy of Queen Elizabeth I, the weather, and the violent moods of the English Channel. The Spanish Habsburg line died in 1700 with poor Charles II who was riddled with congenital deformities and diseases thanks to the family’s penchant for uncle-niece and cousin-cousin marriages, but the Austrian Habsburgs reigned until the 1780 death of the formidable Queen Maria Theresa, mother of Queen Marie Antoinette of France.