Last Monday, Alfonsina Russo, director of the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum, announced the discovery of a tufa sarcophagus and cylindrical stone under the Roman Forum believed to have been part of a shrine to Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. Its position in the stratigraphy of the Forum dates it to the 6th century B.C., making it one of the most ancient monuments in the city.

Last Monday, Alfonsina Russo, director of the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum, announced the discovery of a tufa sarcophagus and cylindrical stone under the Roman Forum believed to have been part of a shrine to Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. Its position in the stratigraphy of the Forum dates it to the 6th century B.C., making it one of the most ancient monuments in the city.

There wasn’t a great deal of information in the release about the find, and the combination of “sarcophagus” and “Romulus” generated a predictable spate of headlines about his tomb maybe having been discovered. The Daily Beast’s “Did Rome Archeologists Uncover Proof of Romulus?” was my favorite. You have to get halfway down the article before the clickbaity question it poses is answered, as it could only ever be, in the negative, even though the story reports on a press conference in which Russo explicitly stated, “This cannot be his tomb.”

But to nerds like me (and you, which is why you’re reading this), there’s plenty of nutritious meat on the bones of those ancient tufa remains without needing to coat them in a sugary BBQ sauce of what-ifs: the traditions and legends underpinning them, sure, but also their significance and connection from the early Republic to the Empire, how they were rediscovered in the modern era with the deployment of new archaeological practices in Rome’s most ancient heart, how they were covered back up during the 1930s as part of Mussolini’s program of recreating a Rome of imperial grandeur (but secretly protected when they could so easily have been destroyed), how they were re-rediscovered again using a combination of old excavation records and ancient sources.

Because this is such a fascinatingly complicated story, my paltry attempt to break down some of those complexities will take a chronological approach, starting with legend as it brushes up against history, and then archaeology, both its practice and the material culture it uncovered.

Let us go then, you and I, back in time to the legendary founding of Rome. You know the story, I’m sure, of how the twins Romulus and Remus, sons of the virgin priestess Rhea Silvia and the god Mars, were condemned to be drowned in the Tiber by her irate uncle. As so often happens in these tales, the people tasked with the unpleasant duty of infanticide chickened out and left the babies next to the banks of the river at flood. There they were found by a lactating she-wolf who suckled them under the shade of a wild fig tree until a swineherd named Faustulus happened by and took them home to raise as his own. They grew into strapping lads keen to found a new city. In 753 B.C. (the traditional date arrived at hundreds of years later by historians following the line of consuls back to the mythical days and using the years of the Olympic Games as a lodestar), Romulus chose the Palatine hill for his, Remus the Aventine. When Remus mocked his brother’s new boundary wall by jumping over it, Romulus killed him. Within that blooded boundary the city of Rome grew, populated first by the exiles and assorted undesirables from neighboring communities, then with Sabine women acquired through treachery and rape, its territory expanded in wars with surrounding tribes.

It was one of those wars — the violent reaction to Rome’s assorted undesirables having kidnapped Sabine maidens and forced them into marriage — that spurred the creation of what would become the very nucleus, political, religious and historical, of the city of Rome. The Sabines had spent a year preparing for this fight. By then their daughters were married to and had children with their abductors and had no desire to see either side slaughtered. When the Sabine women rushed the battlefield pleading that their families and husbands make peace so they would be neither widows nor orphans, the Romans on the Palatine and the Sabines occupying the Capitoline citadel met in the valley between them and laid down their arms. They signed a peace treaty and came together with Romulus and Sabine King Titus Tatius as co-kings of a united people.

It was one of those wars — the violent reaction to Rome’s assorted undesirables having kidnapped Sabine maidens and forced them into marriage — that spurred the creation of what would become the very nucleus, political, religious and historical, of the city of Rome. The Sabines had spent a year preparing for this fight. By then their daughters were married to and had children with their abductors and had no desire to see either side slaughtered. When the Sabine women rushed the battlefield pleading that their families and husbands make peace so they would be neither widows nor orphans, the Romans on the Palatine and the Sabines occupying the Capitoline citadel met in the valley between them and laid down their arms. They signed a peace treaty and came together with Romulus and Sabine King Titus Tatius as co-kings of a united people.

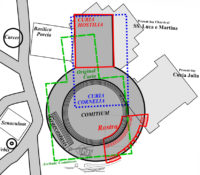

That valley between the hills would grow and evolve over centuries into the Roman Forum, incarnating in its geography the blurry lines between myth and history. The Curiate Assembly, created by Romulus who divided his new city into tribes (curiae) for the purpose of political representation, met there to vote and hold public meetings in the comitium, an open-air space located in what is now the northwest corner of the Forum. Speakers would address the assembled from what would become known in the 4th century B.C. as the rostra, a platform facing the comitium. On the north side of the comitium across from the rostra the first Senate house, the Curia Hostilia, was built by King Tullus Hostilius (r. 673-641 B.C.).

Whatever was left of this ancient building during the turbulent days of the later Republic was demolished by dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In its place and taking over a solid half of the comitium, Sulla built a much larger curia to accommodate the Senate whose membership he had doubled. That one was burned down in 52 B.C. when it was used as an impromptu funeral pyre for Publius Clodius Pulcher after he was killed by the gladiatorial goon squad of his political enemy Titus Annius Milo. It was rebuilt by Sulla’s son Faustus, but was converted into a temple in 44 B.C. by Julius Caesar who built a new Senate house, the Curia Julia, between it and the rostra. It still stands today, albeit extensively rebuilt under Domitian and having spent 1500 years as a church.

Whatever was left of this ancient building during the turbulent days of the later Republic was demolished by dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In its place and taking over a solid half of the comitium, Sulla built a much larger curia to accommodate the Senate whose membership he had doubled. That one was burned down in 52 B.C. when it was used as an impromptu funeral pyre for Publius Clodius Pulcher after he was killed by the gladiatorial goon squad of his political enemy Titus Annius Milo. It was rebuilt by Sulla’s son Faustus, but was converted into a temple in 44 B.C. by Julius Caesar who built a new Senate house, the Curia Julia, between it and the rostra. It still stands today, albeit extensively rebuilt under Domitian and having spent 1500 years as a church.

It is in front of the Curia Julia, 12 feet beneath the masonry nucleus of the long-gone ancient staircase, that archaeologists discovered the tufa sarcophagus.