A unique presentation manuscript given to Queen Elizabeth I by Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker in 1573 has been sold at auction and is at risk of leaving the UK unless a buyer can be found to keep it home. The UK’s Art Minister has placed a temporary export bar on the rare artifact in the hopes a museum or institution can raise its purchase price to keep it in the country.

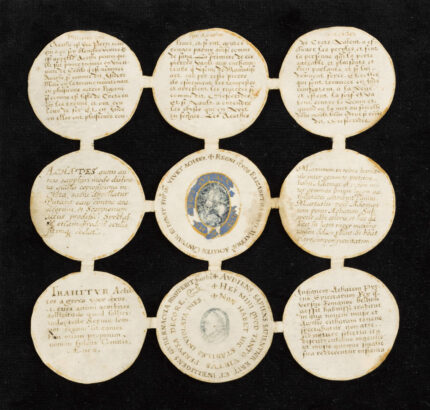

The manuscript takes the unusual form of nine roundels in three rows conjoined by thin strips of vellum. In the middle of the center roundel is an oval blue and gold illumination of St. George and the Dragon bordered by the motto of the Knights of the Garter (“Honi soit qui mal y pense”). A Latin inscription around the edge of the roundel refers to the gift of an agate Archbishop Matthew Parker gave to Queen Elizabeth I.

The center roundel of the bottom row features a miniature profile portrait of Queen Elizabeth in blue. Three Latin aphorisms surround the portrait in three concentric rings. The rest of the roundels all contain inscriptions only. The top row inscriptions define agate in French. The remainder are Latin texts on agate and its property. The different languages are written in different calligraphic scripts, an elegant touch seen in other manuscripts presented to Elizabeth.

The presentation manuscript accompanied a gift, described by Matthew Parker as “a salt cellar made of gold, into the cover of which was inset a jewel, an agate, containing St George killing the dragon, along with verses in French upon the customary royal insignia; in the curved section or hollow of this was enclosed another agate, incised into which was a true likeness of the Queen on white agate. On the top of its cover, a small golden boat held a rectangular diamond.”

Experts believe the “verses in French” he mentions are the actual manuscript, that all nine roundels were folded up to form a single paper circle 1.5 inches in diameter. That disc was then inset into the cover of the precious salt cellar.

The manuscript is an extremely rare surviving artifact directly connected to the summer progresses, the Tudor monarchs’ practice of packing up the court and traveling through the country with a gigantic baggage train, crashing at the luxury pads of assorted nobles and clergy entirely on their dime. Elizabeth did more than two dozen summer progresses during her 44 years on the throne. Crowds of people assembled to behold the spectacle and pageantry of the queen, her courtiers and household parading through town.

On September 7th, 1573, the summer progress was in Canterbury where she, her retinue, the French ambassador and his entourage of 100 were invited to dine at the Archbishop’s Palace by Matthew Parker. It was the Queen’s 40th birthday, so Parker was not only responsible for the expense of feeding, housing and entertaining hundreds of people and one queen with very expensive tastes, but he also had to step up his gifting game. The salt cellar and what it contained — not salt but six Portuguese gold coins — was a showpiece gift. The Archbishop’s son John Parker recorded that for this one visit, Matthew Parker spent more than £2000 in entertainment and gifts alone, not counting the £170 in cash he gave to the Great officers of the Queen’s household.

After the queen’s death, the presentation manuscript fell out of view, remerging a century later in the collection of John Sharp, Archbishop of York. It remained in that family for 300 years until it was sold at auction on December 7th, 2021. The new owner applied to the Culture Ministry for an export license, which has now been deferred until December 1st of this year. If a UK buyer comes forward with the recommended price of £9,450 (plus £390 VAT), the manuscript will stay. If they have a good chunk of that price with evidence of ability to raise the rest, the license will be deferred another six months.

[Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest] Member Peter Barber said:

“These evocative, obscurely-worded and miraculously preserved roundels take us back to power politics and culture at the heart of Elizabeth I’s court. They are a tangible record of a vital and dangerous moment in our religious and political history when the delicately-crafted Anglican Settlement seemed to be in danger, but their wording still has to be fully interpreted and understood.

While Tudor gift lists and sometimes the gifts themselves survive, such intrinsic – but cryptic – evidence for the mentality behind the gift -giving is perhaps unique. I fervently hope the roundels will remain in this country where outstanding collections and libraries – not least that of Archbishop Parker himself – would enable their plentiful remaining mysteries to be investigated and explained with a thoroughness that would simply not be possible elsewhere in the world.”