An ancient cemetery that contains burials of both late Roman and early Saxon funerary traditions has been discovered in the town of Garforth, near Leeds. The excavation has unearthed the remains of more than 60 men, women and children from the significant transitional period between the end of Roman rule in 406 A.D. and the formation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 6th-8th centuries.

An ancient cemetery that contains burials of both late Roman and early Saxon funerary traditions has been discovered in the town of Garforth, near Leeds. The excavation has unearthed the remains of more than 60 men, women and children from the significant transitional period between the end of Roman rule in 406 A.D. and the formation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 6th-8th centuries.

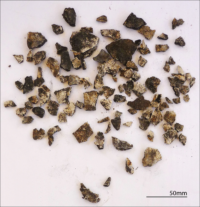

There’s a clear distinction between the Roman graves, which were aligned east-west and the Saxon ones, aligned north-south. The Saxon burials contain typical grave goods like weapons and pottery that are different from the funerary offerings typical of the Roman burials. There are also a few burials that appear to indicate early Christian beliefs.

The most notable find was a lead coffin from the late Roman period. It contained the skeletal remains of an adult woman. Lead coffins were expensive, both in raw materials (large sheets of lead) and the expertise to craft them, so she must have been a member of the elite.

The most notable find was a lead coffin from the late Roman period. It contained the skeletal remains of an adult woman. Lead coffins were expensive, both in raw materials (large sheets of lead) and the expertise to craft them, so she must have been a member of the elite.

The cemetery was discovered last year, but was kept under wraps to give archaeologists the chance to excavate the site secure from would-be looters. An archaeological investigation was triggered before development of the site due to the proximity of late Roman stone buildings and early Anglo-Saxon structures. Some ancient remains were expected to be found, but the discovery of a large cemetery from such a historically significant transitional period came as a happy surprise.

After the retreat of Roman forces from Britain, what is now West Yorkshire was part of the Kingdom of Elmet, a British kingdom rather than an Anglo-Saxon one. Even bounded by Anglian kingdoms to the north and south, Elmet was unusually long-lived for a Brittonic kingdom, extending well into the 7th century when it was finally annexed by the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. This is the first Anglo-Saxon cemetery ever discovered in West Yorkshire.

David Hunter, principle archaeologist with West Yorkshire Joint Services, said: “This has the potential to be a find of massive significance for what we understand about the development of ancient Britain and Yorkshire.

“The presence of two communities using the same burial site is highly unusual and whether their use of this graveyard overlapped or not will determine just how significant the find is. When seen together the burials indicate the complexity and precariousness of life during what was a dynamic period in Yorkshire’s history.

“The lead coffin itself is extremely rare, so this has been a truly extraordinary dig.”

The excavation is now complete, and researchers will now focus on analysis of the skeletal remains. Bones will be radiocarbon dated to establish the timeline of the burials. Stable isotope analysis will also be performed to determine the geographic origins of the deceased. About half of the burials were younger than adult age, and there were several double burials, so researchers will be looking for evidence of disease as well.

The excavation is now complete, and researchers will now focus on analysis of the skeletal remains. Bones will be radiocarbon dated to establish the timeline of the burials. Stable isotope analysis will also be performed to determine the geographic origins of the deceased. About half of the burials were younger than adult age, and there were several double burials, so researchers will be looking for evidence of disease as well.