A large medieval “tableman,” aka gaming piece, has been unearthed from the site of a medieval timber-framed building in Bedfordshire. Its size and decorative style suggest it dates to between the 11th and 13th centuries.

A large medieval “tableman,” aka gaming piece, has been unearthed from the site of a medieval timber-framed building in Bedfordshire. Its size and decorative style suggest it dates to between the 11th and 13th centuries.

Crafted from a cattle mandible, the Bedfordshire piece is 6 cm (2.36 inches) in diameter. It was cut in a circular shape (a central dimple suggests a lathe was used to form it) and then decorated with concentric circles and the ring-and-dot design commonly found on Roman dice and game pieces as well as medieval ones.

Crafted from a cattle mandible, the Bedfordshire piece is 6 cm (2.36 inches) in diameter. It was cut in a circular shape (a central dimple suggests a lathe was used to form it) and then decorated with concentric circles and the ring-and-dot design commonly found on Roman dice and game pieces as well as medieval ones.

Tablemen are so called because they were likely used to play various tables games (with ‘tables’ derived from the Latin tabula, meaning board or plank). In these games, two players would typically roll dice and move their pieces across rows of markings; an example still played today would be backgammon.

Tables games have developed over time and in the Roman period duodecim scripta was likely one of the first to be introduced in Britain. This game uses three rows of twelve markings, although little information has survived regarding gameplay. It is likely that the game ‘tabula’ was refined from duodecim scripta and continued to be played into the medieval period. Tabula is much more similar to backgammon and uses two rows of twenty-four points.

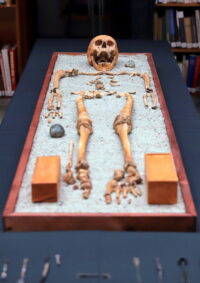

The Museum of Gloucester has a spectacular tabula set from the 11th or early 12th century that is the earliest surviving board and complete set of game pieces known to survive. It was discovered in Gloucester at the site of a Norman castle in 1983, and consists of 24 obelisk-shaped points (the strips pieces moved around on like in backgammon) and 30 pieces carved out of red deer antler and bone. The points were originally inlaid into a wood board, the eponymous tabula, that did not survive.

The Museum of Gloucester has a spectacular tabula set from the 11th or early 12th century that is the earliest surviving board and complete set of game pieces known to survive. It was discovered in Gloucester at the site of a Norman castle in 1983, and consists of 24 obelisk-shaped points (the strips pieces moved around on like in backgammon) and 30 pieces carved out of red deer antler and bone. The points were originally inlaid into a wood board, the eponymous tabula, that did not survive.

The Gloucester pieces are intricately carved with different depictions on each one, among them a horseback rider, a hanging man, an archer, an elephant, a manticore, a fiddler and a centaur with a bow and arrow. They are smaller than the Bedfordshire piece, averaging a diameter of 1.75 inches. None of them have ring-and-dot decoration, not even in the borders, but several of the points from the board do.

The Gloucester pieces are intricately carved with different depictions on each one, among them a horseback rider, a hanging man, an archer, an elephant, a manticore, a fiddler and a centaur with a bow and arrow. They are smaller than the Bedfordshire piece, averaging a diameter of 1.75 inches. None of them have ring-and-dot decoration, not even in the borders, but several of the points from the board do.