A piece of woolen textile discovered in a peat bog four decades ago has been identified as the oldest surviving authentic tartan in Scotland. Dye analysis confirmed that no synthetic dyes were used which suggests it was made before the 1750s and radiocarbon testing narrowed the range down to 1500-1600 A.D. That means it is not only the oldest true tartan (a textile with multiple intersecting stripes in different colors) known to survive, but it was woven within a century or so of the earliest written record of tartan: a purchase made by James III in 1471.

A piece of woolen textile discovered in a peat bog four decades ago has been identified as the oldest surviving authentic tartan in Scotland. Dye analysis confirmed that no synthetic dyes were used which suggests it was made before the 1750s and radiocarbon testing narrowed the range down to 1500-1600 A.D. That means it is not only the oldest true tartan (a textile with multiple intersecting stripes in different colors) known to survive, but it was woven within a century or so of the earliest written record of tartan: a purchase made by James III in 1471.

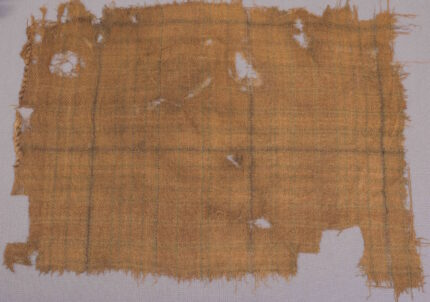

The 55 cm-by-43 cm (22″ x 17″) fragment was discovered in Glen Affric in the Scottish Highlands by peat cutters in the 1980s. Fabric does not usually survive in the harsh soil of Scotland, but the anaerobic environment of the peat preserved the organic material for centuries. Its stripes of green, brown and red were still visible against a tannish-yellow background making it recognizable as tartan. The peat cutters gave the fragment to the Scottish Tartans Authority (STA), who stored it in their textile archive.

V&A Dundee curators came across when looking for examples of early woven checked or plaid textiles for the museum’s upcoming Tartan exhibition. The piece had never been on display and looked a little ratty, but Curator James Wylie noticed that the Glen Affric piece was home-spun and thought it worth further investigation. Experts from the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre performed the dye and radiocarbon analysis.

The first investigation was dye analysis carried out by analytical scientists from National Museums Scotland. Using high resolution digital microscopy, four colours were visually identified for dye analysis: green and brown and possibly red and yellow.

The dye analysis confirmed the use of indigo/woad in the green but was inconclusive for the other colours, probably due to the dyestuff degradation state. However, there were no artificial or semi-synthetic dyestuffs involved in the making of the tartan, which pointed to a date of pre-1750s.

Further clarification on the age of the tartan involved radiocarbon testing at the SUERC Radiocarbon Laboratory in East Kilbride. The process involved washing out all the peat staining, which would have otherwise contaminated the carbon content of the textile.

The cloth is a rustic, loose weave, so despite the presence of red (considered a status symbol by the Gaels of Scotland), this textile was used in practical clothing, likely an outdoor work garment.

The Glen Affric tartan will go on display for the first time at V&A Dundee when the exhibition opens on April 1st. Tartan runs through January 14th, 2024.