A volunteer digger at the Roman auxiliary fort of Vindolanda in Northumberland unearthed a rare silver phalera with a relief of the head of Medusa earlier this month. It was discovered on the floor of a barracks dating to the Hadrianic period of occupation in the 2nd century A.D.

A volunteer digger at the Roman auxiliary fort of Vindolanda in Northumberland unearthed a rare silver phalera with a relief of the head of Medusa earlier this month. It was discovered on the floor of a barracks dating to the Hadrianic period of occupation in the 2nd century A.D.

The silver disc has a raised rim with the bust of Medusa facing the viewer. She has wings on the top of her head and wild wavy hair, the prettified version of the formerly terrifying snake-haired gorgon. The only snakes on the portrait are two slim fellas tied in a knot under her chin like a bolo tie.

Phalerae were worn by centurions and standard-bearers in the Roman legions, emblems of rank and valor. They came in sets of three to 10 roundels mounted on leather straps that buckled on the back. They could be plain discs or decorated with reliefs of deities, animals, mythological creatures or emperors. The Gorgon Medusa was a popular motif for phalerae, breastplates and other military accoutrements as her image was believed to be apotropaic (ie, have the power to ward off evil or bad luck).

Phalerae were worn by centurions and standard-bearers in the Roman legions, emblems of rank and valor. They came in sets of three to 10 roundels mounted on leather straps that buckled on the back. They could be plain discs or decorated with reliefs of deities, animals, mythological creatures or emperors. The Gorgon Medusa was a popular motif for phalerae, breastplates and other military accoutrements as her image was believed to be apotropaic (ie, have the power to ward off evil or bad luck).

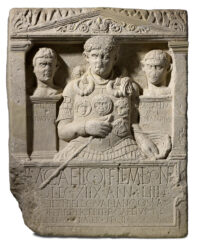

An example comparable to the Vindolanda find is engraved on the tombstone of Roman centurion Marcus Caelius, notable as the only archaeological epigraphic source to explicitly reference the Varian disaster of 9 A.D. Marcus Caelius was the primus pilus (senior centurion)  of the XVIII Legion, one of the three legions Publius Quinctilius Varus led haplessly into an ambush in the Teutoburg Forest that would destroy them all and bring the Roman attempt to conquer Germany beyond the Rhine to a screeching halt. After his death in the calamitous battle, Caelius’ brother had the funerary stone erected in his honor. Now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn, the tombstone depicts the centurion wearing his phalerae. The central roundel, larger than the others, is a gorgoneion.

of the XVIII Legion, one of the three legions Publius Quinctilius Varus led haplessly into an ambush in the Teutoburg Forest that would destroy them all and bring the Roman attempt to conquer Germany beyond the Rhine to a screeching halt. After his death in the calamitous battle, Caelius’ brother had the funerary stone erected in his honor. Now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn, the tombstone depicts the centurion wearing his phalerae. The central roundel, larger than the others, is a gorgoneion.

Phalerae were valuable status symbols and would not have been intentionally discarded. The one at Vindolanda was probably lost by accident, much to its owner’s dismay. It is currently undergoing conservation and will be exhibited next year at the Vindolanda museum.