Archaeologists have discovered two new dolmens at the necropolis of La Lentejuela outside Teba in Andalusia, southern Spain. This brings the total up to 13 dolmens in a necropolis that is less than four hectares in surface area and makes La Lentejuela the densest megalithic site in Andalusia.

Archaeologists have discovered two new dolmens at the necropolis of La Lentejuela outside Teba in Andalusia, southern Spain. This brings the total up to 13 dolmens in a necropolis that is less than four hectares in surface area and makes La Lentejuela the densest megalithic site in Andalusia.

The two newly-discovered dolmens are more than 33 feet long and consist of double stone circles, an outer and an inner ring of stones demarcating an individual burial. Preliminary estimates date the dolmens to the 4th millennium B.C., but further analysis is necessary to determine the dating.

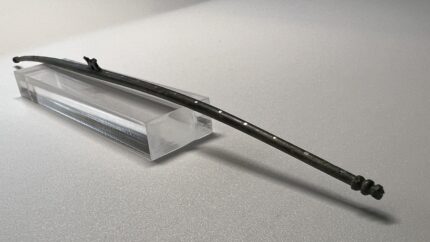

The campaign has also focused on the first phase of excavation of Funeral Structure 1, which is the most monumental. “Once the cover of the tomb was removed and the excavation of its interior began, a dolmen with a more complex architecture than we initially thought has been discovered. We would be in front of a corridor dolmen with certain compartmentalizations. The funerary structure presents a bent corridor (with a curved shape) that gives access to an antechamber, differentiated from the corridor by the presence of two vertical orthostats as jambs. Lastly, we would have a burial chamber separated from the antechamber by two other stelae set in place”, as explained by the professor of Prehistory at the UCA, Eduardo Vijande.

In the current state of the investigation, as stated by those responsible, it is “complex” to specify the date of construction of the monument. What has been documented in this campaign is its reuse at the end of the 3rd millennium or beginning of the 2nd millennium BC “We don’t know when the dolmen was built. As a hypothesis we are considering the end of the IV millennium. What we do know, thanks to this campaign, is that at the end of the 3rd millennium BC it was reused. The Bronze Age populations deposit their deceased in this tomb and even build small spaces inside the dolmen to bury them individually, or at most with two individuals”, affirms Serafín Becerra. “It is quite an interesting question, since in the Bronze Age the idea of a collective burial, as it was originally conceived in the Neolithic, was abandoned and an individualization of death was introduced with the construction of small individual burials inside of the great dolmen,” points out Professor Vijande.

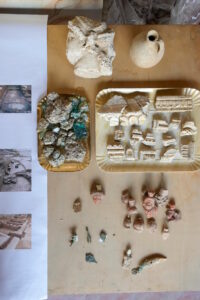

The interdisciplinary team of archaeologists and geologists from the University of Cádiz (UCA) excavating the site have deployed an array of technologies including drone aerial photography, 3D scanning, photogrammetry and differential global navigation satellite system (GNSS) to document the necropolis’ topography, the megalithic monuments and the skeletal remains. The team has also taken samples of archaeological interest for a laboratory analysis that will clarify the chronology of the site and shed new light on the funerary practices employed there in its phases of use.

The interdisciplinary team of archaeologists and geologists from the University of Cádiz (UCA) excavating the site have deployed an array of technologies including drone aerial photography, 3D scanning, photogrammetry and differential global navigation satellite system (GNSS) to document the necropolis’ topography, the megalithic monuments and the skeletal remains. The team has also taken samples of archaeological interest for a laboratory analysis that will clarify the chronology of the site and shed new light on the funerary practices employed there in its phases of use.

After the dolmens were thoroughly recorded, the stones were cleaned and stabilized to prevent deterioration now that they’ve been exposed to the air.