When Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, tore half the sculpted marbles off the Parthenon starting in 1801, he also helped himself to tons of sculptures from other temples and a vast array of antiquities around Athens.

(He did not have permission of Ottoman authorities for this brutal act of pillage, just for the record. The so-called Ottoman firman he claimed had granted him permission does not exist even though all imperial firmans BY LAW were meticulously archived and can be accessed to this day, and the almost-certainly fictional “translation” that does exist does not authorize the removal of pediments, metopes, friezes, caryatids or anything else attached to the Parthenon, only to inscriptions and loose marbles from the area around it. In fact, a local Ottoman official went to stop him when word got out that Elgin was prizing marbles off the structure. Elgin simply bribed him to let him get away with it, just like looters do today.)

His loot was packed into 17 crates and loaded on to his ship, the Mentor, which set sail from Piraeus on September 15th, 1802. Two days later, the ship began to take on water and headed for the nearby Ionian island of Kythera. While attempting to drop anchor off the coast, the ship collided onto the rocks of Cape Avlemonas and sank.

His loot was packed into 17 crates and loaded on to his ship, the Mentor, which set sail from Piraeus on September 15th, 1802. Two days later, the ship began to take on water and headed for the nearby Ionian island of Kythera. While attempting to drop anchor off the coast, the ship collided onto the rocks of Cape Avlemonas and sank.

The 12 people on board were rescued by a passing vessel. The 17 crates of priceless ancient treasures took a little more effort to rescue. Elgin spent large sums organizing a salvage mission performed by local sponge divers that eventually succeeded in raising the Parthenon marbles. They weren’t able to recover all of Elgin’s loot, however, and Greek archaeologists have returned to the Mentor several times over the years to look for lost artifacts. Maritime archaeologists have found amphorae, stone vessels, Egyptian statuary, coins and a number of British objects including bullets, pistols, watches and a compass.

The 12 people on board were rescued by a passing vessel. The 17 crates of priceless ancient treasures took a little more effort to rescue. Elgin spent large sums organizing a salvage mission performed by local sponge divers that eventually succeeded in raising the Parthenon marbles. They weren’t able to recover all of Elgin’s loot, however, and Greek archaeologists have returned to the Mentor several times over the years to look for lost artifacts. Maritime archaeologists have found amphorae, stone vessels, Egyptian statuary, coins and a number of British objects including bullets, pistols, watches and a compass.

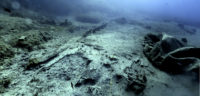

This year’s excavation of the site focused primarily on cleaning, documenting and conservation of the wreck itself. The team cleaned the surviving section of the ship’s hull and took high-resolution photographs of the entire wreck site that were then stitched together digitally to create a photomosaic that will aid in the long-term preservation of the ship’s remains.

This year’s excavation of the site focused primarily on cleaning, documenting and conservation of the wreck itself. The team cleaned the surviving section of the ship’s hull and took high-resolution photographs of the entire wreck site that were then stitched together digitally to create a photomosaic that will aid in the long-term preservation of the ship’s remains.

The moveable objects recovered from the wreck include small parts of the ship — wooden pulleys complete with surviving sections of rope — and artifacts it carried like remarkably intact glazed kitchenware and a section of a wooden leg. The two stand-out artifacts are exquisitely crafted jewels: a gold granulation ring and a pair of gold filigree earrings.

The moveable objects recovered from the wreck include small parts of the ship — wooden pulleys complete with surviving sections of rope — and artifacts it carried like remarkably intact glazed kitchenware and a section of a wooden leg. The two stand-out artifacts are exquisitely crafted jewels: a gold granulation ring and a pair of gold filigree earrings.