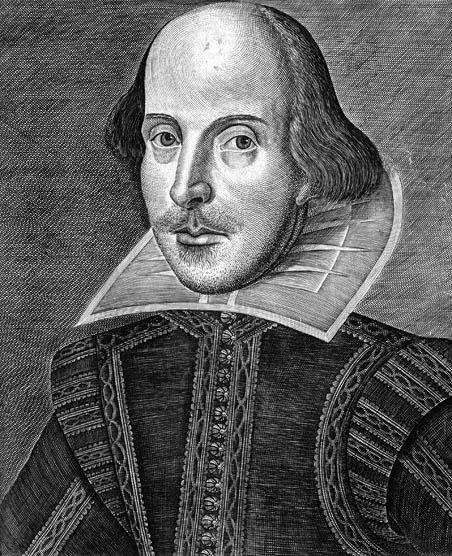

Up until now we haven’t really had reliable portraits of William Shakespeare. Only two are considered canonical: an engraving by Martin Droeshout from the First Folio of his plays published in 1623, and a memorial bust in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Up until now we haven’t really had reliable portraits of William Shakespeare. Only two are considered canonical: an engraving by Martin Droeshout from the First Folio of his plays published in 1623, and a memorial bust in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Shakespeare died in 1616, so both of these images are posthumous, and although there have been a handful of other portraits speculated to be of the bard, none of them have proven to be authentic.

Shakespeare died in 1616, so both of these images are posthumous, and although there have been a handful of other portraits speculated to be of the bard, none of them have proven to be authentic.

According to Stanley Wells, the chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, we have a very likely candidate now in the Cobbe oil painting.

Wells is convinced that an oil painting on wood panel that has rested for centuries in the collection of an old Irish family was painted from life around 1610, when Shakespeare was 46. […]

The painting has languished for centuries outside Dublin at Newbridge House, home base of the Cobbe family, where until recently no one suspected it might be a portrait of the Bard. Three years ago, Alec Cobbe, who had inherited much of the collection in the 1980s and placed it in trust, found himself at an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London called “Searching for Shakespeare.” There he saw a painting from the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., that had been accepted until the late 1930s as a portrait of Shakespeare from life. Looking at it, Cobbe felt certain the Folger painting was a copy of the one in his family’s collection.

Wells ran dendrochronology (tree ring dating) tests on the wooden panel, had it X-rayed and subjected to infrared reflectography. All methods confirm a date of 1610 which suggests the Cobbe painting is not just the only living portrait of Shakespeare, but also the source of later portraits like the Folger painting and the Droeshout engraving.

This confirms indications in the literary record that Shakespeare had a serious fan club when he was alive, serious enough for there to be a demand for images of him.

The Cobb portrait also presents the son of a glovemaker as something of a toff.

“The Cobbe portrait will show people a man who was of high social status,” says Wells. “He’s very well dressed. He’s wearing a very beautiful and expensive Italian lace collar. A lot of people have the wrong image of Shakespeare, and I’m pleased that the picture confirms my own feelings — this is the portrait of a gentleman.”

Not to mention kind of a babe.

Extract from: Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel, „Much Ado About Nothing: why the Cobbe portrait is not an authentic, true-to-life portrait of William Shakespeare”, Frankfurter Rundschau (March 14-15, 2009), pp. 34-35.

“ … A few days ago, ‘the only Shakespeare portrait painted from life’ was once more presented to the public (Richard Brooks, ‘Is this the real Shakespeare at last?’, Sunday Times, 8 March 2009). Alec Cobbe, whose family is said to have owned this picture for 300 years, stated three years ago that at the National Portrait Gallery’s ‘Searching for Shakespeare’ exhibition in 2006 he had come across a Shakespeare portrait (he meant the famous Janssen portrait from the Folger Library in Washington) which looked exactly like one of the pictures in the family collection.

This revelation was quite a surprise to me at the time. For how could Cobbe, of all people, a picture restorer by profession, have overlooked a Shakespeare portrait in his own family’s collection that bore such a striking resemblance to a well-publicised image of the great writer? Today he maintains – solidly backed by Prof. Stanley Wells … – that his picture is a true to life depiction of Shakespeare, and that the Janssen portrait is just one of several copies of the original.

In February 2006, after some ten years of research and collaboration with numerous experts from other disciplines, I presented in book form my proof of the authenticity of four Shakespeare images [Engl. transl.: The True Face of William Shakespeare. The Poet’s Death Mask and Likenesses from Three Periods of His Life. London: Chaucer Press, August 2006]. Shortly before the book was published, I applied the criteria of authenticity I had put together to – among others – the impressive Janssen portrait (known since 1770). I had, however, previously consulted the BKA expert Altmann, who used the Trick Image Differentiation Technique to bring to light significant correspondences. It turned out that – subject to the resolution of certain as yet unanswered questions about its history – this picture too could well be admitted to the small circle of genuine Shakespeare portraits.

Comparing the Janssen portrait (restored in 1988) today with the Cobbe portrait, I was able to establish that in terms of general impression they differ very considerably from each other, and that they do so particularly in regard to morphological and pathological details. This led me to consult the dermatologist Professor Jost Metz, who specialises in diagnosing signs of disease in Renaissance portraits. Metz had earlier submitted his professional opinion concerning the pathological symptom on the forehead of the Flower portrait and the death mask. In his comparative assessment of the two portraits, Cobbe and Janssen, dated 12 March 2009, the dermatologist noted so many important divergences that he doubted ‘whether both portraits featured one and the same subject’. To cite just a few examples: ‘the nose in the Janssen portrait was considerably longer than in the Cobbe portrait’; the distances between the point of the chin and the tip of the nose and alo from the tip to the root of the nose too failed to correspond. The left nostril on the Janssen portrait appeared ‘clearly more flared’ than in the Cobbe. The lips too were different. The lower lip of the Janssen portrait corresponded more to the ‘full’, not to say ‘plump’ (lower) lips which ‘characterised the Davenant bust and the Chandos and Flower portraits’. With regard to the left earlobe, Metz found that the one in the Cobbe portrait appeared misshapen, and did not correspond to that in the Janssen. In contrast to the rims of the eye-sockets (orbit) in the Janssen portrait, whose shape (together with that of the eyebrows) formed a segment of a circle, in the Cobbe picture this area took a ‘more horizontal course’. While the right eyeball of the Janssen painting was higher than the left, in the Cobbe portrait ‘the eyeballs were painted level with each other’. There were also significant differences in the clothing. The ‘patterns of the expensively fashioned collars’ were ‘completely different’, appearing ‘even more intricately worked’ in the Cobbe portrait than in the Janssen.

Particularly important are the divergences apparent in the reproduction or the absence of pathological symptoms. Metz notes that ‘marked annular infiltration (inflamation)’ in the ‘left forehead area’ of the Janssen portrait, ‘in the same location’ as in the Flower portrait and the death mask, was missing from the Cobbe portrait. With regard to the pathological swelling of the left upper eyelid, ‘so conspicuous’ both in the Chandos and the Flower portraits as well as the Droeshout engraving, he states that this ‘pathological alteration’ is to be found also ‘on the upper left eylid’ of the Janssen portrait. But in the Cobbe portrait there was little more than a suggestion of this symptom.

The conclusion is that the painter of the Janssen picture was very well acquainted with the pathological details of Shakespeare’s face – and with its precise morphological characteristics – whereas the Cobbe portraitist was not, or only to a limited extent. While the creator of the Janssen portrait, discovered in 1770, can only have derived this knowledge from the living model, the originator of the Cobbe portrait, which first became known in 2006, appears to have acquired his very limited information at second hand … . My results drew attention to the significant signs of disease visible in Shakespeare’s face for the first time. All of this indicates that the Cobbe painting cannot be an authentic portrait of William Shakespeare painted from life.

This conclusion is supported not only by the youthful appearance of the subject, estimated by Professor Metz as ‘mid-30s’, and certainly not ‘aged 46’; it is also reinforced by the expert opinion of Dr Eberhard J. Nikitsch, a specialist in inscriptions at the Mainz Academy of Science and Literature,dated 11 March 2009. Nikitsch stated that the inscription on the picture – ‘Principum amicitias!’ [‘Be afraid of] the friendship of princes!’ – ‘was not carried out in epigraphic script, but in a cursive hand using a brush’. This was not something one might expect to find ‘in this form at the beginning of the 17th century’. For it lacked ‘the capitals, fracture, and (slightly sloping) italic minuscules’ that are the ‘the scripts normally used for portraits of the time’. As a result, it looks ‘somewhat clumsy, like schoolboy writing’, and must have been added later. …”

For further information see: http://www.hammerschmidt-hummel.de

The claims for the Cobbe portrait

What people are saying – Counter arguments cannot be regarded as valid

Prof. Stanley Wells has rejected objections that have been raised about the Droeshout engraving “looking too different” from the Cobbe portrait by saying that “painters (like photographers) have ever flattered”. He argues that Droeshout “simplified the portrait for his brass plate”, adding that engravers “usually did simplify and update” (see http://www.shakespearefound.org.uk/evidence.html).

These counter arguments cannot be regarded as valid because they are not in accordance with what was common practice in England and on the Continent at the time of Shakespeare. Portraits in the Renaissance were created ad vivam effigiem, i.e. ”from life”, or ”based on the live model”, and reproduced the physiognomy of the subject – together with all the visible signs of illness – with strict verism in order to create a faithful representation of the sitter’s face and actual physical appearance.[1]

In 1582 the eminent Italian theologian Gabriele Paleotti wrote that it was “necessary to ensure that the face or other parts of the body are not rendered more beautiful or more ugly, or changed in any way …, even if he [or she] should be very disfigured by congenital or accidental flaws”.[2]

It is this strict verism or realism, which also applies to the work of the engravers of the time, that enabled the BKA (CID/FBI) experts to identify the sitter of the Chandos and Flower portraits and the Davenant bust as well as the man represented by the Darmstadt Shakespeare death mask. Without this absolute truth to life, the medical experts would not have been able to diagnose the signs of disease in these Shakespearean images, all in the same location, but presented at different stages of life.

Droeshout and the sculptor of Shakespeare’s Stratford funerary bust both depicted the poet accurately, although not directly from life but – as was customary in the Renaissance – from a true-to-life portrait or from a death mask. This is why the Droeshout engraving and the funerary bust formed a perfect comparison basis for investigating and finally authenticating the above-named depictions of Shakespeare.

As I have shown in my article in Frankfurter Rundschau (March 14-15, 2009),[3] there are so many divergencies between the facial features of the Cobbe portrait and the morphological and pathological features of the four authenticated, true-to-life images of the bard (and also the Droeshout engraving and the funerary bust) that it can be ruled out that the sitter of the Cobbe portrait represents William Shakespeare.

Prof. Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel

University of Mainz, Germany

[1] See my book The True Face of William Shakespeare. The Poet’s Death Mask and Likenesses from Three Periods of His Life (London: Chaucer Press, 2006), pp. 21ff.

[2] Quoted in Hammerschmidt-Hummel, The True Face, p. 23.

[3] http://fr-online.de/in_und_ausland/kultur_und_medien/feuilleton/?em_cnt=1689813&

IDK why people say Shakepeare is a ghost name. I know that’s not true. 🙁

Is it certain that ad vivam effigiem means ‘from life, from the live model’? Although that interpretation is frequently found, the Classical Latin for ‘from life, from the live model’ is ex vivo (attested at least in Lucretius and Seneca). On the basis of Classical Latin vivus ‘having the appearance of life, lifelike’ (as applied to works of art, attested at least in Vergil, Statius, and Martial), I wonder whether a better translation of ad vivam effigiem might not be *?’vividly [drawn, painted, and so on]’. Since, however, ad vivam effigiem seems to be a post-Classical usage, I may be wrong in basing that suggestion on Classical usage. The expression needs discussion.