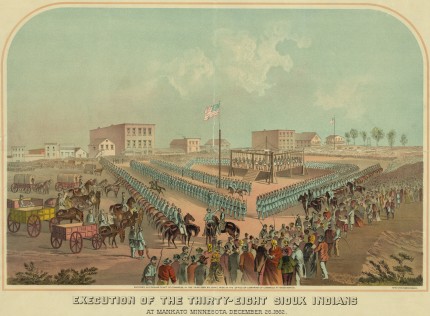

On December 26th, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota. This was the largest mass execution in U.S. history, and it would have been almost 10 times larger had Abraham Lincoln not intervened personally. The backdrop for this horror show was the all-too-common trail of broken treaties between the United States and the Native American tribes who had the misfortune to live in the path of westward expansion.

Under pressure from settlement and the U.S. Army, the Dakota had been forced to cede increasing chunks of territory in return for money and supplies. These treaties signed in the early 1850s were never honorably held to nor enforced. Congress simply chose not to ratify the parts it didn’t like and any payments that were disbursed often got sucked into the black hole of Bureau of Indian Affairs corruption or were paid directly to traders and never made it to the Dakota.

Meanwhile, the territories left to the Dakota in the reservation were hardly safe from U.S. encroachment. With Minnesotan statehood in 1858, large chunks of the reservation were grabbed for settlement, farming, timber, stone quarrying, game and other natural resources. The Dakota began to starve. The Civil War made things worse as supply lines were interrupted and treaty payments became even more irregular.

In August of 1862, negotiations between the Dakota, the government, the state’s Indian Agent and the traders ended at an impasse. The treaty payments hadn’t come through; Agent Thomas Galbraith refused to give the Dakota food without payment; the traders representative Andrew Jackson Myrick also refused to give them food on credit and then added insult to injury by saying “if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung.” Dakota men led by Little Crow went to war against the settlers.

It was a short war. For six weeks between August 17th and September 23rd, 1862, Dakota bands raided settlements and Army forts, killing and kidnapping hundreds. Since there was a Civil War on, the Army wasn’t able to send reinforcements for a little while. A new Army Department was formed on September 6th and manned with brand new Minnesota volunteer regiments. Troops commanded by Colonel Henry Sibley decisively defeated Little Crow and his men at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23rd. The Dakota surrendered on September 26th, releasing 269 captives at a place thereafter known as Camp Release.

It was a short war. For six weeks between August 17th and September 23rd, 1862, Dakota bands raided settlements and Army forts, killing and kidnapping hundreds. Since there was a Civil War on, the Army wasn’t able to send reinforcements for a little while. A new Army Department was formed on September 6th and manned with brand new Minnesota volunteer regiments. Troops commanded by Colonel Henry Sibley decisively defeated Little Crow and his men at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23rd. The Dakota surrendered on September 26th, releasing 269 captives at a place thereafter known as Camp Release.

In the final tally, more than 600 white settlers were killed by the Dakota during the war, only 70 of them soldiers. An estimates 30% of the 600 were children under the age of ten. The stories spread by terrified settlers told of even worse rapes and murders most foul. Sibley immediately appointed a Military Commission to try the Dakota accused of involvement in the war. Two days after the surrender, the trials began.

They continued until November 5th, getting more summary as time passed. Not that they were in any way legitimate, fast or slow. Sibley didn’t have the authority to convene military tribunals, nor did he acknowledge the Dakota legal status as a sovereign nation engaged in a war rather than citizens bound by the criminal code of the United States. Of course the requirements of the criminal code were also entirely disregarded. The defendants had no lawyers or even translators. The evidence presented against them was haphazard and the commissioners blatantly prejudiced. Most of the trials were held in the summer kitchen of trader François LaBathe. It was a sham, a means to stamp a wink-and-nod legitimacy on revenge.

They continued until November 5th, getting more summary as time passed. Not that they were in any way legitimate, fast or slow. Sibley didn’t have the authority to convene military tribunals, nor did he acknowledge the Dakota legal status as a sovereign nation engaged in a war rather than citizens bound by the criminal code of the United States. Of course the requirements of the criminal code were also entirely disregarded. The defendants had no lawyers or even translators. The evidence presented against them was haphazard and the commissioners blatantly prejudiced. Most of the trials were held in the summer kitchen of trader François LaBathe. It was a sham, a means to stamp a wink-and-nod legitimacy on revenge.

Out of the 400 Dakota men tried, 303 were convicted and sentenced to death. Sixteen were sentenced to prison terms. The sentences went to Washington for government approval. President Lincoln reviewed the trial transcripts and found them full of irregularities, to say the least. He would later explain this move to the Senate thus:

“Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.”

There were only two men proven guilty of rape. Lincoln and his lawyers then searched the transcripts for men found guilty of massacres of civilians rather than pitched battles against armed foes. Lincoln’s final list had 39 names of Dakota men to be executed. The rest of the 303 were either freed or sentenced to prison terms.

There were only two men proven guilty of rape. Lincoln and his lawyers then searched the transcripts for men found guilty of massacres of civilians rather than pitched battles against armed foes. Lincoln’s final list had 39 names of Dakota men to be executed. The rest of the 303 were either freed or sentenced to prison terms.

This was not a popular decision. Minnesotans wanted blood and protested the clemency vociferously. The Ministry of the Interior ultimately had to buy them off with reparations for property lost in the war, and even so the Republican  Party suffered in the 1864 election, although they still won the state. Senator Alexander Ramsey, Governor of Minnesota at the time of the trials, would later tell Lincoln that more hangings would have resulted in more electoral votes. Lincoln replied “I could not afford to hang men for votes.”

Party suffered in the 1864 election, although they still won the state. Senator Alexander Ramsey, Governor of Minnesota at the time of the trials, would later tell Lincoln that more hangings would have resulted in more electoral votes. Lincoln replied “I could not afford to hang men for votes.”

On December 26th, 1862, 38 men (one of the men on Lincoln’s list was given a reprieve at the last minute) were led to a massive scaffold in Mankato, Minnesota.

As the men took their assigned places on the scaffold, they sang a Dakota song as white muslin coverings were pulled over their faces. Drumbeats signalled the start of the execution. The men grasped each others’ hands. With a single blow from an ax, the rope that held the platform was cut. Capt. William Duley, who had lost several members of his family in the attack on the Lake Shetek settlement, cut the rope.

After dangling from the scaffold for a half hour, the men’s bodies were cut down and hauled to a shallow mass grave on a sandbar between Mankato’s main street and the Minnesota River. Before morning, most of the bodies had been dug up and taken by physicians for use as medical cadavers.

Following the mass execution on December 26, it was discovered that two men had been mistakenly hanged. Wicaƞḣpi Wastedaƞpi (We-chank-wash-ta-don-pee), who went by the common name of Caske (meaning first-born son), reportedly stepped forward when the name “Caske” was called, and was then separated for execution from the other prisoners. The other, Wasicuƞ, was a young white man who had been adopted by the Dakota at an early age. Wasicuƞ had been acquitted.

To learn more about the Dakota War and its short and longterm effects in Minnesota, please see this exceptional website replete with primary sources and further reading. The New York Times has an excellent article about the efforts to get a posthumous pardon for Chaska or Caske. This article from the Bismark Tribune is remarkably thorough, covering the Dakota war in the larger context of the Indian Wars, the post-war fate of the Dakota and efforts today to cope with this ugly history.

A story over coffee yesterday. A nickel miner from Canada related this: they had a mine up on the Motagua valley where they had dug test pits before the civil war here in Guatemala. After the war, they went back to open their mine back up and found their test pits full of Indians. The man said they covered the pits with dirt and dug new pits. 150 years ago, 20 years ago, the song remains the same.

As a lifelong resident of Minnesota it is especially heartbreaking to read and remember. Thanks for posting this.