More than 1,600 archaeological bones, mainly Medieval, from collections across the UK have been scanned and digitized to create a rich online database of pathological specimens accessible to all. These bones cannot be seen in person by laypeople because they are restricted to scholarly research. In some cases, they are so fragile that even scientists aren’t allowed to handle them. The Digital Diseases team has used 3D laser scanning, computer tomography scans and high resolution photography to create photo-realistic 3D digital models that visitors to the website will be able to examine at a forensic level of detail that wouldn’t be possible in person.

More than 1,600 archaeological bones, mainly Medieval, from collections across the UK have been scanned and digitized to create a rich online database of pathological specimens accessible to all. These bones cannot be seen in person by laypeople because they are restricted to scholarly research. In some cases, they are so fragile that even scientists aren’t allowed to handle them. The Digital Diseases team has used 3D laser scanning, computer tomography scans and high resolution photography to create photo-realistic 3D digital models that visitors to the website will be able to examine at a forensic level of detail that wouldn’t be possible in person.

This record of bones affected by more than 90 pathological conditions like leprosy, bone tumors, tuberculosis, congenital deformations, force trauma both sharp and blunt will be an invaluable resource for medical students, doctors, historians and researchers all over the world who have no access to pathological specimens. The fact that they’re archaeological remains makes them particularly significant because researchers will be able to study the skeletal impact of disease and injury on people who in all likelihood experienced nothing or very little in the way of effective medical intervention. It also gives archaeologists the chance to examine bones taking all the time they need without concern that they won’t be finished before legal reburial requirements kick in.

This record of bones affected by more than 90 pathological conditions like leprosy, bone tumors, tuberculosis, congenital deformations, force trauma both sharp and blunt will be an invaluable resource for medical students, doctors, historians and researchers all over the world who have no access to pathological specimens. The fact that they’re archaeological remains makes them particularly significant because researchers will be able to study the skeletal impact of disease and injury on people who in all likelihood experienced nothing or very little in the way of effective medical intervention. It also gives archaeologists the chance to examine bones taking all the time they need without concern that they won’t be finished before legal reburial requirements kick in.

“We believe this will be a unique resource both for archaeologists and medical historians to identify diseases in ancient specimens, but also for clinicians who can see extreme forms of chronic diseases which they would never see nowadays in their consulting rooms, left to progress unchecked before any medical treatment was available. These bones show conditions only available before either by travelling to see them, or in grainy black and white photographs in old textbooks,” said Andrew Wilson, senior lecturer in forensic and archaeological sciences at the University of Bradford and the lead researcher on the project He added: “I do think members of the public will also find them gripping – they do have what one observer called ‘a grotesque beauty’.”

They’re also just plain interesting. You don’t have to have an aesthetic appreciation of, say, a giant benign bone tumor on a mandible, to find it worth examining and reading about.

The Digital Diseases website officially opens any minute now. It is being launched at an event at the Royal College of Surgeons in London and judging from the project’s Twitter feed, the party has started. The site has a preview on the landing page, but hasn’t gone fully live yet as of this typing. Some images are still missing, some menu links go nowhere, there’s no search function I could find and the home page doesn’t quite exist yet. Still, you can browse categories and click on some examples for more details. Once it is live, visitors will be able to examine bone models in 3D via their web browsers or to download them to their smartphone or tablet device.

The project’s blog is a good place to start right now while the site is still being tinkered with. During the course of the two years spent digitizing the specimens, team members have been blogging about their efforts and particularly interesting bone pathologies they’ve encountered. Take a look at the big hole in this right femur.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/R3T76gjWBw0&w=430]

That’s some gunshot wound. There’s no date on it (I’m sure once the site is functioning we can find that info there), but judging from the big round hole, that was ball shot, like from a musket. Amazingly, the bone is healed, so the injury did not prove to be fatal.

This vertebral column and ribs is an example of advanced ankylosing spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory arthritis that can eventually result in fusion of the spine. That’s what has happened here. Even the ribs have fused to the vertebrae via the ossification of the ligaments attaching them to the spine. Galen first documented some symptoms as distinct from rheumatoid arthritis in the second century A.D., but it wasn’t until the late 19th century that doctors fully identified the disease.

This vertebral column and ribs is an example of advanced ankylosing spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory arthritis that can eventually result in fusion of the spine. That’s what has happened here. Even the ribs have fused to the vertebrae via the ossification of the ligaments attaching them to the spine. Galen first documented some symptoms as distinct from rheumatoid arthritis in the second century A.D., but it wasn’t until the late 19th century that doctors fully identified the disease.

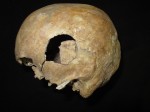

This skull has played a supporting role in the archaeological story of the year/decade/century, the discovery of the skeletal remains of King Richard III. It once belonged to a man who met a bloody end along with so many others during the War of the Roses at the Battle of Towton on March 29th, 1461, Palm Sunday. Inside a mass grave from the battle discovered in 1996, archaeologists found the full articulated remains of 37 men. This was a highly significant find because often in mass graves the remains are so jumbled up it’s impossible to put individuals back together. Articulated skeletons can tell us much more about the injuries sustained in battle and before.

This skull has played a supporting role in the archaeological story of the year/decade/century, the discovery of the skeletal remains of King Richard III. It once belonged to a man who met a bloody end along with so many others during the War of the Roses at the Battle of Towton on March 29th, 1461, Palm Sunday. Inside a mass grave from the battle discovered in 1996, archaeologists found the full articulated remains of 37 men. This was a highly significant find because often in mass graves the remains are so jumbled up it’s impossible to put individuals back together. Articulated skeletons can tell us much more about the injuries sustained in battle and before.

This skull and other bones from the Battle of Towton grave were used by University of Leicester osteologist Dr. Jo Appleby to compare wounds with the skull of the scoliotic skeleton found at the Greyfriars dig site. Richard III and this anonymous but not forgotten fellow both fought and died in the same war, albeit more than 20 years apart (Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth on August 25th, 1485). To confirm that the Richard III candidate’s extensive head wounds properly fit the period’s weapons and battle tactics, Dr. Appleby and Bob Woosnam-Savage, Senior Curator of European Edged Weapons at the Royal Armouries, examined the Towton skull’s peri-mortem weapon injuries. As we now know, they were found to be compatible.

This skull and other bones from the Battle of Towton grave were used by University of Leicester osteologist Dr. Jo Appleby to compare wounds with the skull of the scoliotic skeleton found at the Greyfriars dig site. Richard III and this anonymous but not forgotten fellow both fought and died in the same war, albeit more than 20 years apart (Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth on August 25th, 1485). To confirm that the Richard III candidate’s extensive head wounds properly fit the period’s weapons and battle tactics, Dr. Appleby and Bob Woosnam-Savage, Senior Curator of European Edged Weapons at the Royal Armouries, examined the Towton skull’s peri-mortem weapon injuries. As we now know, they were found to be compatible.

The Digital Diseases database will make that kind of work possible on a far vaster scale since most people in the world aren’t able to visit these collections in person.