Seven months after the Metropolitan Museum of Art returned a pair of 10th-century Khmer statues known as the Kneeling Attendants that had been looted from the Prasat Chen temple in Koh Ker, Cambodia, Sotheby’s has agreed to return a statue looted from the same temple that has been blocked from sale for two years. It’s been a long, arduous process of diplomacy, negotiation and legal wrangling, none of it pretty and some of it impressively nasty, even for a cultural property dispute.

Seven months after the Metropolitan Museum of Art returned a pair of 10th-century Khmer statues known as the Kneeling Attendants that had been looted from the Prasat Chen temple in Koh Ker, Cambodia, Sotheby’s has agreed to return a statue looted from the same temple that has been blocked from sale for two years. It’s been a long, arduous process of diplomacy, negotiation and legal wrangling, none of it pretty and some of it impressively nasty, even for a cultural property dispute.

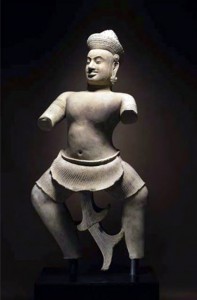

Our story begins more than a 1,000 years ago when King Jayavarman IV moved the capital of the Khmer Empire to Koh Ker, a remote site 75 miles northeast of Siem Reap and the previous capital of Angkor. It was 928 A.D. and up until this point, Khmer sculptural art was characterized by static figures, most of them carved bas reliefs of Hindu deities and mythology. Jayavarman IV commissioned a whole new style of carving for his new capital. In Koh Ker, statues of gods and warriors were made to be freestanding, their poses dynamic captures of figures in movement. One group in front of the western pavilion of Prasat Chen Temple featured 9 statues depicting the final battle between Duryodhana and his nemesis Bhima from the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata. Massive 500-pound sandstone statues of the two enemies were posed facing each mid-fight, surrounded by their supporters.

Koh Ker only remained capital until 944, after which it decayed into ruin while the jungle reclaimed its former dominance. The site’s remoteness was both a blessing and a curse, contributing to its decay and keeping it safe from the kind of predation Angkor was victim to. It wasn’t until the 1950s that French archaeologists recognized Koh Ker’s historical significance and paid regular attention to it. In 1965, the site was explored and documented by Madeleine Giteau, curator of the National Museum, who found it exceptionally well-preserved with the statues and structures virtually untouched. When a French archaeologist returned two years later, he found looting had already begun, thanks in large part to the construction of a new road which made the removal of artifacts to Thailand for sale more practical. Political upheaval and spillover from the Vietnam War put a lot of local armed insurgent groups and foreign fighters in the area and made looting antiquities to sell for hard cash a particularly attractive prospect.

According to an amended complaint from the United States Attorney’s Office of the Southern District of New York, the statue of Duryodhana was cut off its base in around 1972 by an organized network of looters and sold to a dealer in Bangkok. There it was purchased by Douglas Latchford, the same collector of Khmer art who donated the bodies of both Kneeling Attendants and one of their heads to the Met, who arranged for the illegal export of the statue to the London auction house of Spink & Son, the same auction house from which he either bought the Kneeling Attendants directly or acted as a front for the Met to buy them from, depending on whose story you believe. Spink & Son sold Duryodhana to a Belgian collector in 1975. The widow of said collector, Decia Ruspoli di Poggio Suasa, consigned the statue to Sotheby’s for sale in 2010.

According to an amended complaint from the United States Attorney’s Office of the Southern District of New York, the statue of Duryodhana was cut off its base in around 1972 by an organized network of looters and sold to a dealer in Bangkok. There it was purchased by Douglas Latchford, the same collector of Khmer art who donated the bodies of both Kneeling Attendants and one of their heads to the Met, who arranged for the illegal export of the statue to the London auction house of Spink & Son, the same auction house from which he either bought the Kneeling Attendants directly or acted as a front for the Met to buy them from, depending on whose story you believe. Spink & Son sold Duryodhana to a Belgian collector in 1975. The widow of said collector, Decia Ruspoli di Poggio Suasa, consigned the statue to Sotheby’s for sale in 2010.

Duryodhana became the centerpiece of Sotheby’s Asian sale in March of 2011. He was on the cover of the catalog and was extolled as a unique and exceptional example of Khmer artistry. Just hours before it was to go on the block, Cambodian Deputy Prime Minister Sok An sent a letter to the auction house officially requesting the return of the statue as an artifact illegally exported from Cambodia. Sotheby’s withdrew its flagship artifact, estimated to sell for $3 million – $4 million, from the sale. For a year after the first blocked sale attempt, Sotheby’s negotiated with the government of Cambodia to arrange a private sale. Hungarian art collector Istvan Zelnik volunteered to buy the statue for $1 million and donate it to Cambodia.

The talks fell through — Sotheby’s claimed it was the Department of Homeland Security’s fault because they pressured the Cambodian government not to agree to the sale so they could get all the kudos for a diplomatic arrangement; the US Attorney said it was Sotheby’s fault because they turned down the million dollar offer — and in April of 2012, the U.S. Attorney filed a civil suit in federal court seeking forfeiture of the statue on Cambodia’s behalf. Sotheby’s denied strenuously that there was sufficient evidence to prove the statue was looted (even though its matching feet are still in place in Koh Ker), denied knowing all along that it was stolen (even though there’s a long email discussion between the auction house and an expert they contracted to write up the statue before sale in which the expert underscores that it was recently removed from the temple but ultimately suggests they go ahead with the sale because her Cambodian sources say they have no interest in contesting it) and denied that there’s even an applicable law in Cambodian that makes the export of 1,000-year-old Khmer statues illegal.

On Thursday, December 12th, truce was called. Sotheby’s, Decia Ruspoli di Poggio Suasa and the federal government have come to an agreement and I’d say it’s a big win for Cambodia, although as so often happens everyone still gets to deny having willfully trafficked in stolen antiquities.

The Belgian woman who had consigned it for sale in 2011 will receive no compensation for the statue from Cambodia, and Sotheby’s has expressed a willingness to pick up the cost of shipping the 500-pound sandstone antiquity to that country within the next 90 days.

At the same time, lawyers from the United States Attorney’s Office in Manhattan who had been pursuing the statue on Cambodia’s behalf agreed to withdraw allegations that the auction house and the consignor knew of the statue’s disputed provenance before importing it for sale.

The accord said the consignor, Decia Ruspoli di Poggio Suasa, who had long owned the statue, and Sotheby’s had “voluntarily determined, in the interests of promoting cooperation and collaboration with respect to cultural heritage,” that it should be returned.

Andrew Gully, a spokesman for Sotheby’s, said the auction house was gladdened that “the agreement confirms that Sotheby’s and its client acted properly at all times.”

😆 Oh yes, ever so properly. At all times. And ever so voluntary too. It just took them two years and a federal court case to volunteer.

Now we’ll see if the last domino falls: the Norton Simon Art Foundation in Pasadena which owns Duryodhana’s counterpart, Bhima.

They’re all bastards. Should be some kind of international legislation that ensures a country’s treasures, once located, must always be returned there. It’d be simple, eh? – not.

:ohnoes:

People with huge expendable funds equip their livingrooms with …erm …half naked corpulent stolen shadowboxing temple wrestlers whose hands and feet have been cut off, and whose background they do not really understand ? Isn’t that kind of weird ? Well, if these folks really feel a necessity for oddities of this kind, they should probably think about marble copies, as their predecessors did 2000 years ago, when the copy of the ‘Dying Gaul’ from the previous post was made. They apparently had culture back then. Bhima and Duryodhana belong together.

I just sent an email message to the Norton Simon’s curators asking for them to repatriate Bhima. http://www.nortonsimon.org/contact/index.php Anyone else game? We could flood them with requests for Bhima’s return.

Bhima: …Temple wrestler… Pfttt-how sad!

Disgusting!

~

Keep blogging! Thoroughly enjoy the news and expanded info you present here:)

JofO

:skull: