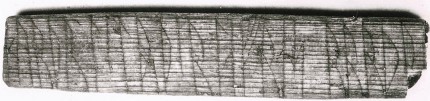

University of Oslo runologist K. Jonas Nordby has cracked an obscure runic code called jötunvillur. Nordby studied the 80 or so coded runic inscriptions that have been discovered in Northern Europe. Out of those 80, nine were written in jötunvillur code which dates to the 12th or 13th century. One of the nine turned out to be a miniature Rosetta stone. Carved on stick found at the old Hanseatic wharf in Bergen, southwest Norway, the inscription features the name of two men, Sigurd and Lavrans, written in both standard runes and jötunvillur.

Each rune has a name. For instance, the rune for “u” is named “urr,” and the rune “m” is named “maðr.” By studying the Sigurd and Lavrans stick, Nordby discovered that the jötunvillur code worked by replacing the rune sign with the last sound in the rune’s name. As you can tell from the two examples, however, many runes end with the same sound, so jötunvillur is very difficult to read unless you have a handy straight rune original right next to it. You have to guess and re-guess to try to make sense of the code, which is why despite the code mechanism now being exposed, the other eight examples of it still haven’t been translated, although Nordby thinks two of them might also be inscribed with proper names: Thorstein on one and Einar on the other.

Because of how difficult it is to read and the prevalence of names, Nordby believes jötunvillur wasn’t used to send secret messages, but rather as an educational tool to teach people the runic alphabet. It was meant to be written, not read, an exercise to help people learn the rune names. There were no schools that taught runes; it was a system passed down from person to person, and what better way to teach it than to make it fun, a game or a code to crack.

Henrik Williams, a professor at Uppsala University’s Department of Scandinavian Languages and a Swedish expert on runes, says that Nordby’s discovery is important.

“Above all, it helps us understand that there were more codes than we were aware of. Each runic inscription we interpret raises our hopes of soon being able to read more. This is pure detective work and each new method improves our chances,” says Williams.

He agrees that the codes could have been used as a tool for learning runes. But he is uncertain how big a role this would have played in the learning process. In any case, Williams thinks the codes were used for much more than communication.

“They challenged the reader, demonstrated skills, and testify to a joy in reading and writing.”

![]() The most commonly used was digit code which divided the alphabet into a matrix of three rows and six columns. The coded figures had a vertical bar with small diagonal ones on either side. The number of bars on the left side of the symbol indicated which row the rune was in; the number of bars on the right side identified the column. Most of the other codes use Caesar Cipher, a relatively simple system named after Julius Caesar who is said to have used it to communicate with his military officers. It just shifts the letters three of four places to the right.

The most commonly used was digit code which divided the alphabet into a matrix of three rows and six columns. The coded figures had a vertical bar with small diagonal ones on either side. The number of bars on the left side of the symbol indicated which row the rune was in; the number of bars on the right side identified the column. Most of the other codes use Caesar Cipher, a relatively simple system named after Julius Caesar who is said to have used it to communicate with his military officers. It just shifts the letters three of four places to the right.

There is a great deal of playfulness evinced in the rune codes that have been cracked. A challenge to decipher the code is a frequent message. They also played with the format itself, hiding runes in the beards of carved figures or in the decoration of an altar. Some appear to be riddles. They’re games, brain teasers, like medieval Scandinavian Sudoku more than magical incantations or secret communications.

There is a great deal of playfulness evinced in the rune codes that have been cracked. A challenge to decipher the code is a frequent message. They also played with the format itself, hiding runes in the beards of carved figures or in the decoration of an altar. Some appear to be riddles. They’re games, brain teasers, like medieval Scandinavian Sudoku more than magical incantations or secret communications.

They do that job well, too, as Henrik Williams’ reaction to the recently cracked code underscores:

“But personally I think jötunvillur is an idiotic code, because whoever made it chose a system that is so hard to interpret. It’s irritating not being able to read it.”

I know that irritation well. I bet he stabs the crossword with his pencil when he can’t complete it.

Pencil! Not pen?

I like to think he’s not quite that hubristic.

Livus!

Just about fell out of the chair at People Mag. online posting this (before you!). xoxo your fan in seattle.

http://www.people.com/people/article/0,,20785834,00.html

That story has been all over the place today. The “kiss me” inscription wasn’t coded in the recently-cracked jötunvillur. It’s digit code. People have known how to translate that for ages. Silly theme headlines. :no: