A year ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art only had a few drawings by French baroque master Charles Le Brun, a major hole in their collection since Le Brun was First Painter of King Louis XIV (the king said Le Brun was “the greatest French painter of all time”) and enormously influential for centuries after his death. The gap was filled in April 2013 when the Met purchased The Sacrifice of Polyxena, the 1647 painting by Charles Le Brun that was discovered in the Coco Chanel Suite of the Paris Ritz during renovations in 2012, for $1,885,194. That price set a new world record for a work by Le Brun.

A year ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art only had a few drawings by French baroque master Charles Le Brun, a major hole in their collection since Le Brun was First Painter of King Louis XIV (the king said Le Brun was “the greatest French painter of all time”) and enormously influential for centuries after his death. The gap was filled in April 2013 when the Met purchased The Sacrifice of Polyxena, the 1647 painting by Charles Le Brun that was discovered in the Coco Chanel Suite of the Paris Ritz during renovations in 2012, for $1,885,194. That price set a new world record for a work by Le Brun.

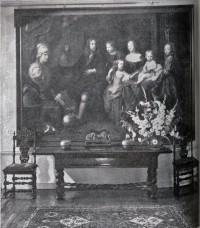

It’s not a record anymore. The Met just broke its own record and broke it hard, acquiring the monumental portrait Everhard Jabach and His Family for an unprecedented $12.3 million. The reason the price is so high this time is that while Polyxena is an early work of a historical theme, Jabach is a group portrait painted around 1660 at the peak of Le Brun’s powers and popularity. It’s a massive work — 7.6 feet by 10.6 feet — of massive artistic and historical significance.

Jabach was one of the great personalities of his age. He was portrayed twice by Van Dyck (1636, private collection;1641, Hermitage, Saint Petersburg), by Peter Lely and possibly Sébastien Bourdon (both ca. 1650, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne), and by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1688, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne). Le Brun was one of the sitter’s favorite artists and the two were united—in the words of Claude Nivelon, Le Brun’s earliest biographer—by “friendship and shared interests” (‘il était uni d’amitié et d’inclination’). The family group was one of the few pictures Jabach did not sell to the King of France, and therefore one of the few that did not enter the collection of the Louvre.

The picture is at once a portrait of family relations and of a painter’s relationship to a key patron. The assemblage of objects lying on the floor at the feet of Jabach symbolizes his cultural interests: a Bible, an open copy of Sebastiano Serlio’s architectural treatise, a compass (architecture and geometry), a porte crayon and drawn sheet (drawing), an ancient marble head (sculpture), a book (literature and poetry), and a celestial globe (astronomy). Most prominent among these objects is a bust of Minerva, goddess of wisdom and the arts. She is identified by her distinctive helmet and the Medusa on her chest. Behind Jabach is the mirror in which we see Le Brun at work.

Le Brun made two copies of the portrait. This one is the first. The second was acquired by the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (now the Bode Museum) in Berlin in 1836 but was destroyed in May of 1945 when the Friedrichshain flak tower, where it had ironically been sent for safekeeping along with more than 400 of the museum’s most prized paintings, caught fire at least twice. This was after of Berlin had fallen, by the way, not the result of shelling or bombing. All we have left of it today is an old black and white photograph.

Le Brun made two copies of the portrait. This one is the first. The second was acquired by the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (now the Bode Museum) in Berlin in 1836 but was destroyed in May of 1945 when the Friedrichshain flak tower, where it had ironically been sent for safekeeping along with more than 400 of the museum’s most prized paintings, caught fire at least twice. This was after of Berlin had fallen, by the way, not the result of shelling or bombing. All we have left of it today is an old black and white photograph.

The primary copy was thought lost, but it turns out to have been part of the furniture of the stately home of Olantigh Towers in Kent for almost two centuries. It was brought to the UK by Henry Hope, a wealthy Boston-born, Rotterdam-based Scot who purchased the painting in 1792 from Johann Matthias von Bors, a descendant of Jabach’s. Hope installed it in his Harley Street home after fleeing the continent and the chaos of the French Revolution in 1794. It moved to Olantigh Towers in 1832 when it was bought by John Samuel Wanley Sawbridge Erle-Drax.

In 1913, Olantigh Towers was sold to one J. H. Loudon who then sold to his son, F. W. H. Loudon in 1935. The painting was just sold along with the house. No particular mention was made of it. It was rediscovered last year when experts from Christie’s were called in to assess the contents of the home. Christie’s contacted the Metropolitan Museum and negotiated the sale.

In 1913, Olantigh Towers was sold to one J. H. Loudon who then sold to his son, F. W. H. Loudon in 1935. The painting was just sold along with the house. No particular mention was made of it. It was rediscovered last year when experts from Christie’s were called in to assess the contents of the home. Christie’s contacted the Metropolitan Museum and negotiated the sale.

Because of the complex composition representing prominent subjects and their relationship to the artist, this portrait has been called “a French Las Meninas,” after the iconic  masterpiece painted by Diego Velázquez in 1656. It’s no wonder, then, that the UK didn’t want to let it go. It’s the only Le Brun portrait in the country and in February the government’s Export Reviewing Committee placed a temporary three-month export ban on the painting, giving British museums the chance to raise the $12.3 million necessary to keep it in the country. The ban expired on May 6th with no institutions stepping up to the plate or even raising enough money to make it remotely plausible that they might be able to acquire it should the ban be extended.

masterpiece painted by Diego Velázquez in 1656. It’s no wonder, then, that the UK didn’t want to let it go. It’s the only Le Brun portrait in the country and in February the government’s Export Reviewing Committee placed a temporary three-month export ban on the painting, giving British museums the chance to raise the $12.3 million necessary to keep it in the country. The ban expired on May 6th with no institutions stepping up to the plate or even raising enough money to make it remotely plausible that they might be able to acquire it should the ban be extended.

And so the Met gets its prize Le Brun, doubling the number of paintings by the artist in the museum, and more than doubling the importance of their 17th century French collection. The portrait will be conserved and framed, a process that will take the rest of this year at least. It will go on display in the Met’s European Paintings Galleries in 2015. They already have the portrait’s entry uploaded to the museum website, however, and it has lots of details about the imagery and significance of the piece.

I sometimes think that I wouldn’t be too bothered if I never saw a painting again, with the exceptions of (i) the work of the Dutch masters, (ii) of Turner, and (iii) portraits by various hands.

You could lock me in a room with Turners and nothing else and I’d live out the rest of my life quite happily.

I don’t understand why “The Sacrifice of Polyxena” was removed and sold during the renovation of Ms. Chanel’s apartment. Shouldn’t that have remained as a significant important artifact reflecting her exquisite taste for acquisitions? (I shudder when I see some of these before and after “renovations” that usually amount to a gut and redo.)

Coco Chanel didn’t acquire the painting herself. It belonged to the Ritz, like most of the furnishings in the room, although there’s no record of how it got there. Mohamed Al Fayed, owners of the Ritz, decided to sell it because he felt its quality deserved a more fitting setting than a hotel room, ideally a museum. He donated the money to charity.

This used to be one of our annual treats.

http://www.nationalgalleries.org/media/_file/press_releases/turner_2011_press_release.pdf

Thank you for your explanation. The charitable donation was very generous and admirable.

I know I’m probably late to the game but I’m just finishing reading “The Monuments Men” which explains why this painting was probably still available for sale. If you love art and haven’t read the book you should. The world came close to an art Armageddon in WWII. It is an amazing story.

A very interesting story, thank you! In my case, it has doubled the amount of Le Brun’s work in my collection – so far I had only one such, The Repentant Magdalen (1655), also an early work of him (and with a smaller mirror). This is a colossal one, I didn’t even know that they produced such large mirrors (we mostly see them in the paintings of 18th century, but not so early).