Last October, researchers from the University of Pisa opened the tomb of Henry VII of Luxembourg (1275-1313), King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, in Pisa Cathedral to study the remains and grave goods. Inside the coffin they found his bones wrapped in a silken shroud. On top of the bundle were a crown, a

Last October, researchers from the University of Pisa opened the tomb of Henry VII of Luxembourg (1275-1313), King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, in Pisa Cathedral to study the remains and grave goods. Inside the coffin they found his bones wrapped in a silken shroud. On top of the bundle were a crown, a scepter and an orb, the classic trappings of imperial power, all in gilded silver.

scepter and an orb, the classic trappings of imperial power, all in gilded silver.

It was the shroud that proved the biggest surprise. When it was carefully unfurled, the rectangular cloth was just shy of 10 feet long and four feet wide. Woven out of silk in the 14th century, the shroud has horizontal bands about four inches wide in alternating colors of orangey  brown (originally red) and blue. Embroidered on the blue strips with silver and gold thread are lions facing each other. The formerly red bands have some kind of decoration as well, but it’s in the same tonal range and can’t be identified with the naked eye. At the top of the textile is a dark red band with thin borders of golden yellow. There are traces of an inscription on the red band, but it’s not decipherable yet.

brown (originally red) and blue. Embroidered on the blue strips with silver and gold thread are lions facing each other. The formerly red bands have some kind of decoration as well, but it’s in the same tonal range and can’t be identified with the naked eye. At the top of the textile is a dark red band with thin borders of golden yellow. There are traces of an inscription on the red band, but it’s not decipherable yet.

To top it all off, the edges along the length of the entire cloth are finished with selvages and the top and bottom edges are finished with checkered bands. That means this textile is complete, the full width of the loom on which it was woven. For such an exceptionally delicate textile to survive complete for 701 years is incredibly rare, unique even. It will be an invaluable source of information on the silk-weaving industry in the early 14th century, and if the inscription and decoration can be fully deciphered, it will also add to our understanding of Henry and his reign.

To top it all off, the edges along the length of the entire cloth are finished with selvages and the top and bottom edges are finished with checkered bands. That means this textile is complete, the full width of the loom on which it was woven. For such an exceptionally delicate textile to survive complete for 701 years is incredibly rare, unique even. It will be an invaluable source of information on the silk-weaving industry in the early 14th century, and if the inscription and decoration can be fully deciphered, it will also add to our understanding of Henry and his reign.

This isn’t the first time Henry VII’s tomb has been opened. It was opened before in 1727 and again in 1921. Researchers found a lead cylinder in the coffin with a parchment that was left behind in 1727, and the report from the 1921 intervention is extant. It describes the cloth as “a fine shroud woven in bands,” rather a dramatic understatement considering what a treasure it is. Archaeologists today have a much higher estimation of textiles than they did a century ago.

This isn’t the first time Henry VII’s tomb has been opened. It was opened before in 1727 and again in 1921. Researchers found a lead cylinder in the coffin with a parchment that was left behind in 1727, and the report from the 1921 intervention is extant. It describes the cloth as “a fine shroud woven in bands,” rather a dramatic understatement considering what a treasure it is. Archaeologists today have a much higher estimation of textiles than they did a century ago.

Celebrated as the “alto Arrigo” (high Henry) in Dante’s Divine Comedy, Henry is best remembered for his struggle to reestablish imperial control over the city-states of 14th-century Italy.

He was crowned King of Germany in 1308 and two years later he descended into Italy with the aim of pacifying destructive disputes between Guelf (pro-papal) and Ghibelline (pro-imperial) factions. His goal was to be crowned emperor and restore the glory of the Holy Roman Empire.

After meeting strong opposition among anti-imperialist Guelf lords, Henry entered Rome by force, and was indeed crowned Holy Roman Emperor on June 29, 1312.

“He who came to reform Italy before she was ready for it,” as Dante described Henry VII, died just a year after his coronation, having failed to defeat opposition by a secular Avignon papacy, city-states and lay kingdoms.

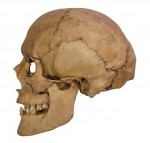

Henry died on August 24th, 1313, 16 days after launching a campaign against his greatest enemy Robert of Anjou, King of Naples. He is thought to have died of malaria, but the timing is obviously suspicious and there were immediately rumors that he had been poisoned. There was no time to preserve his corpse, so his people took drastic measures to skeletonize it. His body was burned until the flesh was incinerated, then the bones were soaked in wine for preservation. The head was removed and boiled leaving a clean skull. There were ashes in the coffin and signs of charring on the bones.

Henry died on August 24th, 1313, 16 days after launching a campaign against his greatest enemy Robert of Anjou, King of Naples. He is thought to have died of malaria, but the timing is obviously suspicious and there were immediately rumors that he had been poisoned. There was no time to preserve his corpse, so his people took drastic measures to skeletonize it. His body was burned until the flesh was incinerated, then the bones were soaked in wine for preservation. The head was removed and boiled leaving a clean skull. There were ashes in the coffin and signs of charring on the bones.

The rough beginning was compounded over the centuries by multiple moves of the coffin to different locations inside the cathedral. The face area of the skull was badly damaged. An anthropologist on the team reconstructed the skeleton and cranium, which allowed researchers to estimate Henry’s height and age. He was about 1.78 meters tall (about 5'10") and around 40 years old when he died. His knees showed signs of having been used extensively in genuflecting prayer. A high concentration of arsenic was found in his bones, and the symptoms of arsenic poisoning — nausea, vomiting, muscle cramps, convulsions — could be confused for a number of natural illnesses, including malaria. Arsenic was a very popular poison in medieval and Renaissance Italy, especially among the upper classes. It even earned the monicker “the poison of kings.”

The rough beginning was compounded over the centuries by multiple moves of the coffin to different locations inside the cathedral. The face area of the skull was badly damaged. An anthropologist on the team reconstructed the skeleton and cranium, which allowed researchers to estimate Henry’s height and age. He was about 1.78 meters tall (about 5'10") and around 40 years old when he died. His knees showed signs of having been used extensively in genuflecting prayer. A high concentration of arsenic was found in his bones, and the symptoms of arsenic poisoning — nausea, vomiting, muscle cramps, convulsions — could be confused for a number of natural illnesses, including malaria. Arsenic was a very popular poison in medieval and Renaissance Italy, especially among the upper classes. It even earned the monicker “the poison of kings.”

That doesn’t necessarily mean Henry VII was deliberately poisoned, however. Arsenic was a common ingredient in medications. Hippocrates himself used an arsenic compound to treat ulcers and abscesses, and once Albertus Magnus isolated arsenic in 1250, the pure element was used to treat everything from skin conditions to venereal diseases to fevers and malaria.

That doesn’t necessarily mean Henry VII was deliberately poisoned, however. Arsenic was a common ingredient in medications. Hippocrates himself used an arsenic compound to treat ulcers and abscesses, and once Albertus Magnus isolated arsenic in 1250, the pure element was used to treat everything from skin conditions to venereal diseases to fevers and malaria.

The artifacts from the tomb are being kept in the Museum of the Cathedral while researchers continue to study the contents. Small fragments of bones have been sent to specialized labs for analysis. Hopefully the results will reveal more about Henry’s life, death and the treatment his body received after death.

Very interesting, thanks for posting.

I do wonder though about what people’s understanding of arsenic was during the Medieval/Renaissance period. On the one hand you write about arsenic being used as a medicine, but then also write about arsenic being a choice poison among nobles. Did they regard it like classic chemotherapy, something useful but deadly in too great a quantity?

I think they imagined that different preparations and applications would have different effects. Arsenic was used as a medicine well into the 19th century. It was also used in cosmetics, so it wasn’t just a fighting fire with fire approach.

Good for the folks who opened the casket in the past, all the stones appear to still be in the crown. I wonder if the scepter is supposed to resemble some kind of fruit, with the leaves just below it. The lions look like they were made with a automatic loom, but I’m not sure they had them that far back. If made by hand that was one amazing weaver, such talent! I hope they use the skull to do a facial reconstruction, that would be fascinating!

Is the Cathedral in Pisa no longer consecrated? I’m a bit surprised the church authorities would allow the exhumation of anyone given a Christian burial.

Like many historically and artistically important places of worship, Pisa Cathedral operates as a museum (one of several in the central Pisan museum circuit)while continuing to carry out the functions of a church and cathedral. According to Church law and practice, there are strict guidelines for exhumation and the subsequent treatment of the body. It happens relatively often–and not only in the Catholic context.

Thanks for the information, Edward.

Your blog never ceases to amaze and educate me !!

I take exception to the statement that the cloth was woven to the full width of the loom. With respect, it is possible to weave less than the width of the loom: without the loom being present, we have no idea how wide it was.

The selvedges tell us we do have the complete width of the cloth.

They should bury Harry after they are done poking around his bones. Let the dead man lay. :chicken: :skull:

This kind of pattern weaving was done by hand, using fingers and pickup sticks to lift sections of warp as needed for each part of the pattern. The weavers were indeed very skilled: I can do simple pattern variations using 3 or 4 warps, and know people who create complex tapestries by hand on standing looms (and sometimes repair old weavings). Modern computerized mechanical looms make possible fast production of long complex designs on many layers of warp, but are not at all essential for the creation of bands of ornament such as this, or for the beautiful centuries old rugs and tapestries made by hand on the simplest of looms. As they are still made today.

As for the width of the loom, a point brought up in a post below, there is no reason to assume the loom was less than the width of this piece. Yes, it is possible to weave a wide piece on a narrow loom, but the fact that this piece is silk, which is vulnerable to abrasion, and is woven with decorative bands in place, makes reasonable the assumption that the loom was at least 4 feet wide.

In fact, it strikes me as rather silly to think otherwise under the circumstances. A wide loom would have been available to a man buried in an eminant cathedral in a zinc box, with gold grave goods indicating his status and wealth.

Very interesting article. It is amazing that the shroud is in a good a shape as it looks from the photo. Especially after the nuber of times the grave has been opened. Thanks for sharing.