The Codex Chimalpahin, a seminal three-volume handwritten indigenous history of pre-Hispanic and 16th century Mexico, has returned to Mexico after almost 200 in the archives of the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS). The codex was slated to be sold at a Christie’s auction in London on May 21st of this year. Before the sale, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) contacted Christie’s in the hope they could acquire the codex privately. The BFBS was glad to work with them so that this founding document of national significance could go home.

The Codex Chimalpahin, a seminal three-volume handwritten indigenous history of pre-Hispanic and 16th century Mexico, has returned to Mexico after almost 200 in the archives of the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS). The codex was slated to be sold at a Christie’s auction in London on May 21st of this year. Before the sale, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) contacted Christie’s in the hope they could acquire the codex privately. The BFBS was glad to work with them so that this founding document of national significance could go home.

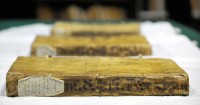

The day before the auction, INAH became the delighted new owner of the Codex Chimalpahin. The three volumes arrived in Mexico on August 18th, 2014, where they were secured in the vault of the National Library of Anthropology and History. On September 17th, the Codex Chimalpahin was welcomed home in an official ceremony attended by officials from the government, INAH and the National Museum of Anthropology (MNA). The next day the Codex Chimalpahin went on display in the Mexican Codices: Memories and Knowledge exhibition at the MNA along with 43 other codices from the National Library vault that have never been exhibited to the public before.

The day before the auction, INAH became the delighted new owner of the Codex Chimalpahin. The three volumes arrived in Mexico on August 18th, 2014, where they were secured in the vault of the National Library of Anthropology and History. On September 17th, the Codex Chimalpahin was welcomed home in an official ceremony attended by officials from the government, INAH and the National Museum of Anthropology (MNA). The next day the Codex Chimalpahin went on display in the Mexican Codices: Memories and Knowledge exhibition at the MNA along with 43 other codices from the National Library vault that have never been exhibited to the public before.

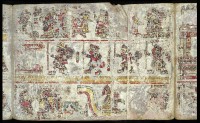

The Codex Chimalpahin is considered the first history of Mexico. It’s a collection of several chronicles, calendars, lists of rulers, locations, accounts of the Spanish conquest and more written in Nahuatl and Spanish. Prominent in the first two volumes are the writings of Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (b. between 1568 and 1580 – d. 1648), a direct descendant of Ixtlilxochitl I and Ixtlilxochitl II, rulers of Texococo, and of Cuitláhuac, the penultimate ruler of Tenochtitlan. He was heir to their titles and property, but unfortunately there wasn’t much of the latter. Educated in Nahuatl and Spanish, Alva Ixtlilxochitl had a profound knowledge of his ancestors’ oral histories, songs and traditions. He worked his whole life for the people who ruled the land his fathers had ruled as a translator and historian. He died in poverty.

The Historia Chichimeca. a history of the Nahua peoples through the Spanish conquest from the Texoca perspective, is Alva Ixtlilxochitl’s most enduring work. It’s in the Codex along with several other of his writings. They are the only surviving copies of his histories in his own handwriting. Volume One even has his signature.

The Historia Chichimeca. a history of the Nahua peoples through the Spanish conquest from the Texoca perspective, is Alva Ixtlilxochitl’s most enduring work. It’s in the Codex along with several other of his writings. They are the only surviving copies of his histories in his own handwriting. Volume One even has his signature.

Most of Volume Three was written by Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin (b. 1579 — d. 1660), a Nahuatl historian who also claimed to be a descendant of Aztec rulers. His Nahuatl names mean “Runs Swiftly with a Shield” (Chimalpahin) and “Rises Like an Eagle” (Quauhtlehuanitzin), and the first of them gives the codex its name. His writings were not commissioned by the Spanish viceroys, unlike Alva Ixtlilxochitl’s. They were written in Nahuatl for Nahuatl readers. There are only six of his works extant in his own handwriting. The other five were already in public institutions and now this last one is as well.

The manuscripts were compiled and bound into three volumes by Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (b. 1645 – d. 1700), a poet, historian, former Jesuit, philosopher and all-around intellectual born in Mexico City of Spanish parents. He had a particular interest in the indigenous cultures and created a legendary library of native documents, including manuscripts by Chimalpahin and Alva Ixtlilxochitl. He in fact became good friends with Don Juan, the son of Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, who gifted him many of his father’s works to thank him for his help in a lawsuit against Spanish settlers trying to steal his property near the great pyramids at San Juan Teotihuacan. After Don Juan died, he bequeathed the rest of his collection to Sigüenza.

The manuscripts were compiled and bound into three volumes by Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (b. 1645 – d. 1700), a poet, historian, former Jesuit, philosopher and all-around intellectual born in Mexico City of Spanish parents. He had a particular interest in the indigenous cultures and created a legendary library of native documents, including manuscripts by Chimalpahin and Alva Ixtlilxochitl. He in fact became good friends with Don Juan, the son of Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, who gifted him many of his father’s works to thank him for his help in a lawsuit against Spanish settlers trying to steal his property near the great pyramids at San Juan Teotihuacan. After Don Juan died, he bequeathed the rest of his collection to Sigüenza.

Much of Sigüenza’s famed library was acquired by Italian-born antiquary and ethnographer Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci (b. ca. 1702 – d. ca. 1753). Benaduci fell afoul of the Spanish viceroy and in 1743 he was arrested and his collection impounded. Although eventually Benaduci was absolved and the King ruled his collection should be returned to him, it never was. During the years it was kept in the office of the viceroyalty, it was horribly neglected and many items disappeared. Parts of the collection can be found in the Berlin State Library, the National Library in Paris and the National Museum of Anthropology.

The Codex Chimalpahin fell into the hands of priest, politician, historian José María Luis Mora Lamadrid (b. 1794 – d. 1850). One of his favored political causes was national literacy. To further that aim, in 1827 he made what seems like a completely insane deal with James Thomsen of the British and Foreign Bible Society: already rare original handwritten works by Alva Ixtlilxochitl and Chimalpahin in return for a bunch of Protestant Bibles to be used in a national literacy campaign.

The Codex Chimalpahin fell into the hands of priest, politician, historian José María Luis Mora Lamadrid (b. 1794 – d. 1850). One of his favored political causes was national literacy. To further that aim, in 1827 he made what seems like a completely insane deal with James Thomsen of the British and Foreign Bible Society: already rare original handwritten works by Alva Ixtlilxochitl and Chimalpahin in return for a bunch of Protestant Bibles to be used in a national literacy campaign.

The codex was never published or even studied. Once it left Mexico, scholars who would seek out such a source had no idea where it was. It was considered lost until it showed up like magic in the Christie’s sale. Now it’s on display in Mexico and, once the exhibition ends in January, it will be made available to researchers at the National Library of Anthropology and History.

He apparently excavated too: Lorenzo Boturini, when referring to the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan: ‘I had made a map of the pyramid which I have in my collection and on circumambulating it I observed that the celebrated Don Carlos de Siguenza y Gongora had attempted to breach it with drills, when he met with resistance; the centre is known to be hollow’ (1746:143), cited in I. Bernal: A History of Mexican Archaeology (‘Translated from the Spanish’, London 1980).

:hattip:

Are there plans for an English translation and, if so, where may it be read or obtained?

Arthur J. O. Anderson has it out in two volumes with Susan Schroeder.