It was drizzling in Chicago on Saturday, July 24th, 1915, but the damp weather didn’t keep the employees of the Western Electric Company from hastening to the Chicago River wharf where they would board one of five steamers that would transport them four hours across Lake Michigan to the amusements of Washington Park in Michigan City, Indiana. The Western Electric annual picnic was particularly well-attended, with almost 7,000 employees, family and friends planning to go. The first chartered steamer to board passengers was the SS Eastland, a 12-year-old ship that had been designed without a keel and was top-heavy from inception.

Ballast tanks filled with water were supposed to balance out the weight, but nonetheless the Eastland had had multiple listing incidents over the course of its short career.

Ballast tanks filled with water were supposed to balance out the weight, but nonetheless the Eastland had had multiple listing incidents over the course of its short career.

A month before the Western Electric picnic, the Eastland had more weight added to its top in the form of additional lifeboats, a reaction to the recent passage of the Seaman’s Act (itself a reaction to the sinking of the Titanic) which required increased lifesaving devices on ships. The act didn’t go into effect until the end of the year, but the steamship company decided to get the jump on it. It did not decide to lower the ship’s passenger capacity, however, although by the terms of the Seaman’s Act the Eastland would go from being licensed to carry 2,500 passengers to a capacity of 1,200.

Unaware that their ship had a history of top-heaviness, that it was even top-heavier right then than it had ever been thanks to all the new lifeboats and rafts on the top deck, and that there were twice as many of them as future regulation would allow, 2,500 picnickers boarded the Eastland. As soon as they got on the ship started listing. Still moored to the wharf, the steamer listed to starboard, then to port. The passengers thought it was fun at first and the captain thought he could fix it, so he didn’t order an immediate evacuation. At 7:31 AM, the Eastland rolled all the way onto its port side and capsized in 20 feet of water a few feet from dry land.

Unaware that their ship had a history of top-heaviness, that it was even top-heavier right then than it had ever been thanks to all the new lifeboats and rafts on the top deck, and that there were twice as many of them as future regulation would allow, 2,500 picnickers boarded the Eastland. As soon as they got on the ship started listing. Still moored to the wharf, the steamer listed to starboard, then to port. The passengers thought it was fun at first and the captain thought he could fix it, so he didn’t order an immediate evacuation. At 7:31 AM, the Eastland rolled all the way onto its port side and capsized in 20 feet of water a few feet from dry land.

People who had been milling about on the upper decks were dumped into the Chicago River. Whoever was able to scramble over the starboard rail as the ship turned remained dry on the exposed starboard side of the capsized vessel. The passengers below deck (and there were many, particularly women and children), with the good sense but bad luck to stay out of the rain, were trapped. Disoriented in the sideways ship, crushed by falling furniture, fixtures and people, flooded by the water rushing into the interior, they died from drowning, blunt force trauma, and trampling.

Eight hundred and forty-four people died in the hull of the Eastland. Twenty-two families were completely annihilated, and more than 650 families lost at least one member. Nineteen families lost both parents. One hundred and seventy-five women, three of them pregnant, were widowed; 84 men were left widowers. Of the victims who lost their lives, 228 were teenagers and 58 were babies or young children. Seventy percent of the dead were under 25 years of age; the average age of the victims was 23. The Eastland tragedy remains to this day Chicago’s worst disaster in terms of loss of life.

Eight hundred and forty-four people died in the hull of the Eastland. Twenty-two families were completely annihilated, and more than 650 families lost at least one member. Nineteen families lost both parents. One hundred and seventy-five women, three of them pregnant, were widowed; 84 men were left widowers. Of the victims who lost their lives, 228 were teenagers and 58 were babies or young children. Seventy percent of the dead were under 25 years of age; the average age of the victims was 23. The Eastland tragedy remains to this day Chicago’s worst disaster in terms of loss of life.

The tugboat Kenosha, which was tied to the Eastland in preparation to tow it from the river to the lake, immediately changed gears to rescue. Captain John O’Meara had the tug moored to the wharf so passengers who had managed to climb onto the starboard side of the Eastland as it rolled could use the tug as a floating bridge to walk to safety. Divers were enlisted to search for survivors, or more realistically to recover bodies, inside the capsized ship. They had to break through the sides of the ship using cutting torches.

The tugboat Kenosha, which was tied to the Eastland in preparation to tow it from the river to the lake, immediately changed gears to rescue. Captain John O’Meara had the tug moored to the wharf so passengers who had managed to climb onto the starboard side of the Eastland as it rolled could use the tug as a floating bridge to walk to safety. Divers were enlisted to search for survivors, or more realistically to recover bodies, inside the capsized ship. They had to break through the sides of the ship using cutting torches.

Rescue and recovery was only the beginning. With so many dead and so many more living rushing to the riverside clamouring to know the fate of their loved ones, storing and identifying the dead and alerting their families would become a logistical nightmare. Western Electric just happened to be incredibly well-positioned to live up to the challenge.

The Western Electric Company made equipment for the Bell System, a network of local phone companies either directly owned by or closely connected to AT&T. Originally formed to make telegraph machinery in 1869, the company went through several iterations before AT&T bought a controlling stake in the company in 1881. Western Electric became the exclusive manufacturer of AT&T telephones in 1882. By the early 20th century it was also manufacturing or reselling a wide range of electrical appliances like dishwashers, toasters, radios and vacuüm cleaners.

The Western Electric Company made equipment for the Bell System, a network of local phone companies either directly owned by or closely connected to AT&T. Originally formed to make telegraph machinery in 1869, the company went through several iterations before AT&T bought a controlling stake in the company in 1881. Western Electric became the exclusive manufacturer of AT&T telephones in 1882. By the early 20th century it was also manufacturing or reselling a wide range of electrical appliances like dishwashers, toasters, radios and vacuüm cleaners.

It manufactured the parts for the Transcontinental Line that linked sea to shining sea by voice. The first transcontinental phone call, from Alexander Graham Bell in New York City to Dr. Watson in San Francisco, was made in January of 1915, just six months before the disaster. (And yes, Bell did repeat his famous line, “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you” for the test. Watson replied that it would take him a week since he wasn’t in the room next door this time.) Instantaneous voice communication across 3,000 miles was an exciting technological leap forward for Western Electric and its employees, and that buzz was part of the reason the picnic was so enthusiastically embraced that summer.

The company had a paternalistic, almost Hershey-like approach to its employees. Productivity, Western Electric believed, could be improved by creating a supportive, active, family environment. The Hawthorne Works plant, built in Cicero, Illinois in 1905, had a band, gym, restaurant, library, baseball field, bowling alley and track field. Eventually it would have its own hospital, fire department and police. Employees were encouraged to join teams, be they baseball, soccer, bowling or chess. The company saw sports and friendly competition were a way for employees to get to know each other, to work together as a team, maybe even get a rivalry going on between people or departments that would egg them on to make more phones.

The company had a paternalistic, almost Hershey-like approach to its employees. Productivity, Western Electric believed, could be improved by creating a supportive, active, family environment. The Hawthorne Works plant, built in Cicero, Illinois in 1905, had a band, gym, restaurant, library, baseball field, bowling alley and track field. Eventually it would have its own hospital, fire department and police. Employees were encouraged to join teams, be they baseball, soccer, bowling or chess. The company saw sports and friendly competition were a way for employees to get to know each other, to work together as a team, maybe even get a rivalry going on between people or departments that would egg them on to make more phones.

The company offered evening classes for all employees, men and women. The classes could be related to the job or purely for one’s edification. Then there were the social entertainments: dances, masquerades, movies, concerts, ice skating, and the culmination of the season, the annual employee picnic.

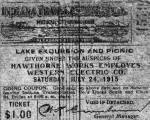

Organized by employee social clubs for the first four years, the fifth annual Hawthorne Works picnic in 1915 burst the boundaries of the clubs and became its own thing, generating a shockingly vast panoply of committees to attend to every little aspect of the day. Committees included Program, Judges, Prizes, Beach, Dancing, Tug-of-War, Amusement, Picnic, Transportation, Tickets, Photography, Grounds, Music, Publicity, Athletics and Races. It was the Transportation Committee that arranged with the Indiana Transportation Company to charter five large ships to carry the throngs to the picnic site.

Organized by employee social clubs for the first four years, the fifth annual Hawthorne Works picnic in 1915 burst the boundaries of the clubs and became its own thing, generating a shockingly vast panoply of committees to attend to every little aspect of the day. Committees included Program, Judges, Prizes, Beach, Dancing, Tug-of-War, Amusement, Picnic, Transportation, Tickets, Photography, Grounds, Music, Publicity, Athletics and Races. It was the Transportation Committee that arranged with the Indiana Transportation Company to charter five large ships to carry the throngs to the picnic site.

When the disaster struck, Western Electric employees who had been waiting to board their own ships for the party used some of the teamwork developed on the company baseball diamond to band together for the recovery, identification and notification for their fallen comrades. They and other volunteers set up temporary morgues in warehouses and in the Second Regiment Armory. They created multiple information bureaus to make a list of names of the dead and collect information from frantic next of kin. They had dozens of phones installed so the information bureaus could share data instead of duplicating each others’ work, and to receive the many phone calls from worried friends and family. They scoured hospitals for living and dead. They sorted an enormous quantity of personal belongings that had been taken from dead bodies in the hopes of identifying them, as well as from the inside of the ship.

When the disaster struck, Western Electric employees who had been waiting to board their own ships for the party used some of the teamwork developed on the company baseball diamond to band together for the recovery, identification and notification for their fallen comrades. They and other volunteers set up temporary morgues in warehouses and in the Second Regiment Armory. They created multiple information bureaus to make a list of names of the dead and collect information from frantic next of kin. They had dozens of phones installed so the information bureaus could share data instead of duplicating each others’ work, and to receive the many phone calls from worried friends and family. They scoured hospitals for living and dead. They sorted an enormous quantity of personal belongings that had been taken from dead bodies in the hopes of identifying them, as well as from the inside of the ship.

That’s just scratching the surface. After identification there was relief, providing some financial support for the families of the dead. The Eastland Memorial Society has digitized a transcript of the August 1915 edition of the Western Electric News, a memorial issue dedicated to those who perished in the disaster. Read this page for the company’s account of its employees’ dedication, ingenuity and heroism in extremely trying circumstances. For a contrasting viewpoint, read Carl Sandburg’s very different take on events in the International Socialist Review.

The wreck and its tragic aftermath were thoroughly documented by the press. Groundbreaking photojournalist Jun Fujita, the first Japanese-American photojournalist and one of the first photojournalists period, had just been hired by the Chicago Evening Post. He happened to be at work bright and early on July 24th, 1915, so he was able to run to the wharf as soon as he heard about the disaster. Fujita took pictures of the capsized ship and the crowd of passengers perched on top of it. He clambered onto the ship and got some very compelling shots of the rescue efforts, including one of a wharfman carrying the dead body of a child. The tough old dock worker with a horrified look in his eyes as he holds a young victim in his arms became a symbol of the disaster in the same way the firefighter tenderly cradling the bloody baby after the Oklahoma City bombing became an iconic image. Jun Fujita wrote a poignant essay about the day’s events as seen through the agonized eyes of the rescue worker with the dead child in his arms.

The wreck and its tragic aftermath were thoroughly documented by the press. Groundbreaking photojournalist Jun Fujita, the first Japanese-American photojournalist and one of the first photojournalists period, had just been hired by the Chicago Evening Post. He happened to be at work bright and early on July 24th, 1915, so he was able to run to the wharf as soon as he heard about the disaster. Fujita took pictures of the capsized ship and the crowd of passengers perched on top of it. He clambered onto the ship and got some very compelling shots of the rescue efforts, including one of a wharfman carrying the dead body of a child. The tough old dock worker with a horrified look in his eyes as he holds a young victim in his arms became a symbol of the disaster in the same way the firefighter tenderly cradling the bloody baby after the Oklahoma City bombing became an iconic image. Jun Fujita wrote a poignant essay about the day’s events as seen through the agonized eyes of the rescue worker with the dead child in his arms.

There was no film of the disaster known to have survived. That changed on Thursday. University of Illinois Ph.D. candidate Jeff Nichols was looking through that magnificent time sink that is Europeana, the digital database of Europe’s cultural patrimony, doing research for his dissertation on World War I propaganda when he saw the intertitle of a Dutch newsreel refer to the Eastland. Then he found a second clip in another newsreel. Both movies were uploaded to Europeana’s exceptional World War I site, Europeana 1914-18, by the EYE Film Instituut Nederland which has contributed hundreds of hours of archival footage to the database.

The first clip is a segment (starts 1:08) of a newsreel that otherwise covers World War I-related events, mainly in England. The only exceptions are the opening scene of Bersaglieri, an Italian light infantry unit famous for their signature black grouse feather hats and the brisk trot they use instead of a parade march, taking the town of Cormons on the border with Austria-Hungary, and the second scene of the rescue efforts around the capsized Eastland.

The second clip (starts 9:10), also a segment of a newsreel covering home front events, records the salvage crews working to right the Eastland on August 14th, almost four weeks after the disaster.

The Eastland’s owners were tried in a Chicago court for criminal neglect, but the jury acquitted them. The steamer itself was repaired, renamed the USS Wilmette, and used as a training ship for the Navy until it was finally broken up for scrap in 1947.

The Eastland’s owners were tried in a Chicago court for criminal neglect, but the jury acquitted them. The steamer itself was repaired, renamed the USS Wilmette, and used as a training ship for the Navy until it was finally broken up for scrap in 1947.

Hawthorne Works went the way of so much midwestern manufacturing. Employer to more than 40,000 people at its peak, the plant closed its doors permanently in 1986, and shortly thereafter the brick industrial buildings were demolished to make way for a hideous strip mall. Only the water tower and a cable factory, now used by the county as a warehouse, remain of the original campus.

The Chicago History Museum has a display on the Eastland disaster in the City in Crisis section of its permanent exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America. Go to the Eastland Disaster Historical Society website for tons of information about the disaster and its aftermath. The organization was founded by the two granddaughters of a survivor of the disaster, and it is a labor of love and respect. Not to be missed is their meticulous reconstruction of the passenger list with links to more information and photographs about the victims and survivors.

The Chicago History Museum has a display on the Eastland disaster in the City in Crisis section of its permanent exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America. Go to the Eastland Disaster Historical Society website for tons of information about the disaster and its aftermath. The organization was founded by the two granddaughters of a survivor of the disaster, and it is a labor of love and respect. Not to be missed is their meticulous reconstruction of the passenger list with links to more information and photographs about the victims and survivors.

My father is a ‘freighter freak’, so we grew up knowing all about the Great lake shipwrecks. I have known about this one all my life; it was splendid to see some video; what a find! What a treat!

A bit of personal connection: My father was a naval reservist who trained on the USS Wilmette in the 1930s.

Another bit of trivia: The Wilmette actually sank a German U-boat. After WWI a surrendered German U-boat was taken on a bond drive cruise of the Great Lakes cities. The last stop was Chicago. After that the Navy didn’t have any plans for the U-boat. It ended up being sunk as a target by gunfire from the Wilmette. I read a report several years ago that divers had found the wreck of the U-boat on the bottom of Lake Michigan.