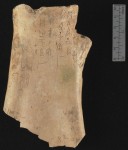

Oracle bones are inscribed ox shoulder blades or the flat underside of turtle shells that were used for divination in Shang dynasty China (ca. 1600-1046 B.C.). The Shang was China’s second dynasty and the oracle bones are the oldest surviving texts in the Chinese language. They are the main source historians have about Shang China and Bronze Age China in general, but were only recognized as the immense cultural patrimony they are in 1899. Antiquarian Wang Yirong found some oracle bones being sold in Peking as “dragon bones” which were ground into powder and used in traditional medicine to staunch a bleeding wound. He recognized they were engraved with ancient script. The oracle bones were dated to the Shang dynasty when the origin of the ones floating around in markets was discovered near the village of Xiaotun in Henan Province, the Shang capital.

Oracle bones are inscribed ox shoulder blades or the flat underside of turtle shells that were used for divination in Shang dynasty China (ca. 1600-1046 B.C.). The Shang was China’s second dynasty and the oracle bones are the oldest surviving texts in the Chinese language. They are the main source historians have about Shang China and Bronze Age China in general, but were only recognized as the immense cultural patrimony they are in 1899. Antiquarian Wang Yirong found some oracle bones being sold in Peking as “dragon bones” which were ground into powder and used in traditional medicine to staunch a bleeding wound. He recognized they were engraved with ancient script. The oracle bones were dated to the Shang dynasty when the origin of the ones floating around in markets was discovered near the village of Xiaotun in Henan Province, the Shang capital.

The late 19th, early 20th century was a turbulent time in China. Cultural patrimony issues were not governmental priorities and foreign scholars and collectors stepped into the void. One of them was Lionel Charles Hopkins, brother and biographer of the famous poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, a diplomat who went to China in 1874 and remained there until his retirement in 1908. He collected almost 900 oracle bones which he studied over the four decades of his retirement. He died in 1952 at the age of 98. Hopkins left his oracle bone collection to Cambridge University.

Hopkins broke a lot of ground in the study of oracle bones, but he too was fooled by fakes. There were so many of them that for a couple of decades after their discovery, the authenticity of all of them were in question. It was only when excavations began in the late 1920s at Xiaotun that large numbers of oracle bones were confirmed to be part of the Shang royal archive. About 200,000 thousand bone fragments are known today, a quarter of which are inscribed.

Diviners used the oracle bones to invoke the ancestors of the Shang dynasty royal family who were believed to know the future. They were also thought to have influence on future events. When a Shang royal wanted to know the outcome of a war, the success of a harvest, an impending natural disaster or anything else, they turned to diviners and their oracle bones. On the reverse of the bones diviners carved out divots known as divination pits. The pits were exposed to fire, creating vertical cracks with a short perpendicular crack halfway down on the obverse of the bone. The cracks were interpreted as answers to the diviners’ questions and those questions were engraved next to the crack. The divination served double duty: predicting the future and securing the benign intervention of the ancestors. The inscriptions are invaluable records of Shang society, and can be of international import. One of the oracle bones in the Hopkins Collection is the oldest dated record of a lunar eclipse known in the world.

Diviners used the oracle bones to invoke the ancestors of the Shang dynasty royal family who were believed to know the future. They were also thought to have influence on future events. When a Shang royal wanted to know the outcome of a war, the success of a harvest, an impending natural disaster or anything else, they turned to diviners and their oracle bones. On the reverse of the bones diviners carved out divots known as divination pits. The pits were exposed to fire, creating vertical cracks with a short perpendicular crack halfway down on the obverse of the bone. The cracks were interpreted as answers to the diviners’ questions and those questions were engraved next to the crack. The divination served double duty: predicting the future and securing the benign intervention of the ancestors. The inscriptions are invaluable records of Shang society, and can be of international import. One of the oracle bones in the Hopkins Collection is the oldest dated record of a lunar eclipse known in the world.

The texture of the bones and writing is important to historians, as are the divination pits and cracks. Within a couple of years of Wang Yirong’s discovery, rubbings of the inscriptions were published in books and suddenly collectors were clamouring to buy oracle bones. As usually happens when there’s an overwhelming demand for a finite material, unscrupulous dealers quickly produced as many forgeries as possible. Many oracle bones have both original engravings, pits and cracks, and forged text added to make a simple bone look fancier. The more text, the more expensive the artifact. Sorting out the genuine from the fraud requires careful examination of the bones, their inscriptions and cracks.

Since the earliest discoveries, the surface of oracle bones were captured with rubbings. In 1982, oracle bone expert Mme. Qi Wenxin visited the UK to make rubbings of all the bones in public and private collections. Cambridge’s Hopkins Collection was one of her stops. These rubbings are not the kind you made on gravestones in 5th grade art class with a crayon and tracing paper. Mme. Qi’s tools were a brush made of fine human hair, the finest quality Chinese black ink, very thin tissue-like paper, a piece of silk wrapped around natural cotton and a water infused with the herb baiji (Bletilla Rhizome). Baiji is used in traditional Chinese medicine to stop bleeding and reduce swelling, but infused in the rubbing water, it helps the paper adhere to the bone. If plain water was used, the paper would come off during rubbing.

Since the earliest discoveries, the surface of oracle bones were captured with rubbings. In 1982, oracle bone expert Mme. Qi Wenxin visited the UK to make rubbings of all the bones in public and private collections. Cambridge’s Hopkins Collection was one of her stops. These rubbings are not the kind you made on gravestones in 5th grade art class with a crayon and tracing paper. Mme. Qi’s tools were a brush made of fine human hair, the finest quality Chinese black ink, very thin tissue-like paper, a piece of silk wrapped around natural cotton and a water infused with the herb baiji (Bletilla Rhizome). Baiji is used in traditional Chinese medicine to stop bleeding and reduce swelling, but infused in the rubbing water, it helps the paper adhere to the bone. If plain water was used, the paper would come off during rubbing.

The side of the bone not being rubbed was fixed to the table with putty. Then the paper was placed on top and brushed with the baiji solution. Mme. Qi tapped the wet paper into the engraving by lightly hitting it with the human hair brush until every letter of the inscription showed through the paper. When the paper was dry, the silk-wrapped cotton was dabbed into the sticky ink and stippled on with care not to cake it on too thickly. Once the ink layer dried, another was applied. The process was repeated until the inscription becomes clear, a white negative against the inky black background. You can see Mme. Qi at work in this video.

The side of the bone not being rubbed was fixed to the table with putty. Then the paper was placed on top and brushed with the baiji solution. Mme. Qi tapped the wet paper into the engraving by lightly hitting it with the human hair brush until every letter of the inscription showed through the paper. When the paper was dry, the silk-wrapped cotton was dabbed into the sticky ink and stippled on with care not to cake it on too thickly. Once the ink layer dried, another was applied. The process was repeated until the inscription becomes clear, a white negative against the inky black background. You can see Mme. Qi at work in this video.

Now the Cambridge University Library has taken the first step in establishing a new kind of archive. It has scanned the first of the 614 oracle bones in its collection in high resolution 3D. As far as we know, it’s the first oracle bone in the world to be 3D scanned.

The image brings into sharp focus not only the finely incised questions on the obverse of the bone, but also the divination pits engraved on the reverse and the scorch marks caused by the application of heat to create the cracks (which were interpreted as the answers from the spirit world). These can be seen more clearly than by looking at the actual object itself, and without the risk of damage by handling the original bone.

Once scanned, a precise replica of the bone was 3D printed so it can handled and examined by students and researchers who would otherwise not be allowed access to the originals for conservation purposes. If the 3D scanning trend catches on, there’s another exciting possibility: that more of the hundreds of thousands of fragments may be pieced back together thanks to computer matching.

Cambridge UL Oracle Bone CUL.52 Hi Res

by Professor Dominic Powlesland

on Sketchfab

This is fascinating. !!

Fascinating article, thank you! Would like to know more about what system was used to scan the bone and what 3D printer was used to make the replica.

I couldn’t find more information about the scanner, but the replica was made with a hospital printer, specifically a printer used at Addenbrooke’s Hospital to help plan and practice maxillofacial and orthopaedic surgery. The bone print is made of a fine powdered plaster hardened with superglue.

Hi, what would you advise someone to do if they had oracle bones?the type of the Shang Dynasty. Along with many other items of the same period.

HI Darcy, Do you still have them? Are you planning to sell any?