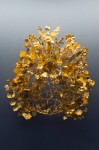

On June 9th, Duke’s of Dorchester auction house will be selling an ancient gold myrtle wreath kept for years in a box under a bed in Somerset. Duke’s appraiser Guy Schwinge went to the cottage to examine some of the belongings of the elderly resident. He was amazed when the owner pulled a busted old cardboard box out from under the bed, dug through the crumpled up newspaper and fished out a Hellenistic gold wreath. It’s a hoop of pure gold with gold myrtle leaves and flowers attached that obscure the hoop and give it the look of a natural myrtle wreath when seen from the front. The workmanship is very fine, with delicate veining on the leaves and details like the anthers and filaments of the flowers.

On June 9th, Duke’s of Dorchester auction house will be selling an ancient gold myrtle wreath kept for years in a box under a bed in Somerset. Duke’s appraiser Guy Schwinge went to the cottage to examine some of the belongings of the elderly resident. He was amazed when the owner pulled a busted old cardboard box out from under the bed, dug through the crumpled up newspaper and fished out a Hellenistic gold wreath. It’s a hoop of pure gold with gold myrtle leaves and flowers attached that obscure the hoop and give it the look of a natural myrtle wreath when seen from the front. The workmanship is very fine, with delicate veining on the leaves and details like the anthers and filaments of the flowers.

The style suggests it dates to around the 2nd or 3rd century B.C., but its exact age can’t be determined.

“It is notoriously difficult to date gold wreaths of this type. Stylistically it belongs to a rarefied group of wreaths dateable to the Hellenistic period and the form may indicate that it was made in Northern Greece,” [said Guy Schwinge].

“It is eight inches across and weighs about 100 grams. It’s pure gold and handmade, it would have been hammered out by a goldsmith.

“The wreath is in very nice condition for something that’s 2,300 years old. It’s a very rare antiquity to find, they don’t turn up often. I’ve never seen one in my career before.”

I’ve never seen an ancient Hellenistic gold wreath with those hoops at the end of the circlet before. The current owner, who prefers to remain anonymous, inherited the piece from his grandfather. He doesn’t know anything about it. He is quoted in the article saying that his grandfather traveled extensively in the 1940s and 1950s, including in northwest Greece near the border, but the Duke’s auction catalogue says it was acquired by the seller’s grandfather in the 1930s.

It’s all a bit shady, especially since according to the article there are still bits of dirt embedded in the wreath. Dirt suggests recent excavation, not something that was bought legitimately 60, 70 or even 80 years ago. Gold wreaths are expensive, small and portable which makes them highly desirable to looters. In 2006 the Getty had to return one they had bought in 1993 from a “Swiss private collection,” ie, a gang of Greek smugglers, to Greece. In 2012 traffickers were caught red-handed trying the sell a looted gold wreath in Greece. On the other hand, there are plenty of nooks and crannies in the hammered sheet gold for dirt to nestle in for the long haul. If it was never professionally cleaned, it’s possible that some of the soil from its burial place stuck over decades.

It’s all a bit shady, especially since according to the article there are still bits of dirt embedded in the wreath. Dirt suggests recent excavation, not something that was bought legitimately 60, 70 or even 80 years ago. Gold wreaths are expensive, small and portable which makes them highly desirable to looters. In 2006 the Getty had to return one they had bought in 1993 from a “Swiss private collection,” ie, a gang of Greek smugglers, to Greece. In 2012 traffickers were caught red-handed trying the sell a looted gold wreath in Greece. On the other hand, there are plenty of nooks and crannies in the hammered sheet gold for dirt to nestle in for the long haul. If it was never professionally cleaned, it’s possible that some of the soil from its burial place stuck over decades.

It almost certainly was deliberately buried as a funerary offering. Wreaths of braided flowers, grasses, leaves and branches were used in ancient Greece and Rome as symbols of victory, honor and sovereignty crowning the heads of Olympic athletes, generals on the battlefield, even literary giants like Ovid and Virgil. Wreaths also symbolized the ascension to immortality or apotheosis, often seen in funerary monuments held over the head of a deified emperor, for example.

Myrtle, along with laurel, palm, oak, olive, grape vines and ivy, were popular wreath motifs. The myrtle was associated with the goddess Aphrodite, symbolizing love and immortality. Myrtle wreaths were worn at weddings, by victorious athletes and by initiates into the Eleusinian mysteries. In Rome, the Corona Ovalis was given to a military commander determined by the Senate to be worthy of an ovation (a ceremony a step short of a triumph) for a victory realized without bloodshed.

Myrtle, along with laurel, palm, oak, olive, grape vines and ivy, were popular wreath motifs. The myrtle was associated with the goddess Aphrodite, symbolizing love and immortality. Myrtle wreaths were worn at weddings, by victorious athletes and by initiates into the Eleusinian mysteries. In Rome, the Corona Ovalis was given to a military commander determined by the Senate to be worthy of an ovation (a ceremony a step short of a triumph) for a victory realized without bloodshed.

Gold versions of the wreaths during the Hellenstic period were placed in graves as funerary offerings for the honored dead or dedicated to the gods in sanctuaries. They were too fragile for use as crowns or diadems in life. They are best known from the graves of Macedonian rulers — a gold myrtle wreath believed to have beloned to Meda, fifth wife of Philip II of Macedon, was found in the royal tombs at Vergina — but Hellenistic gold wreaths have been found as far afield as southern Italy and the Dardanelles.

Gold versions of the wreaths during the Hellenstic period were placed in graves as funerary offerings for the honored dead or dedicated to the gods in sanctuaries. They were too fragile for use as crowns or diadems in life. They are best known from the graves of Macedonian rulers — a gold myrtle wreath believed to have beloned to Meda, fifth wife of Philip II of Macedon, was found in the royal tombs at Vergina — but Hellenistic gold wreaths have been found as far afield as southern Italy and the Dardanelles.

The articles about the Somerset wreath say it could sell for as much as £100,000 ($146,000), but Duke’s is far more circumspect. The pre-sale estimate is £10,000-20,000 ($14,600-29,000).

Since this wreath came into England during an undetermined time period, wouldn’t the British law disallowing these treasures to leave the nation, go into effect?

ALSO…

I would think the soil – tucked amongst the details of the design – could be tested to determine the approximate location of origin. There are many questions surrounding this piece. It might be wise if it was taken off the auction block till all answers are secured.

Whadda find!

A very handsome piece in seemingly fine condition–but rather subdued in style and workmanship, compared with many other Hellenistic gold wreaths (which tend to look rather more like the other two examples you showed.) There are several currently on view in the spectacular “Pergamon” show at the Met.

Since the wreath was found under an English bed, not under English soil, it would presumably not qualify as “treasure trove”. And since it has no meaningful English historical connection (no one even knew that it was in the country), it would not seem to be an element of “national heritage”. If the wreath was going to expropriated, it would be for return to Greece (or Macedonia, or Turkey, or Bulgaria, or wherever–if the soil samples are sufficient to disprove the claim of Greek geographical origin

). In any case, the burden of proof is seemingly on the claimant nation in demonstrating that the work was illegally exported after 1970–which is the generally accepted UNESCO cut-off date.

If this golden wreath had been in the England for many years / perhaps centuries, it could have been quietly exchanged as a payment, held as a keepsake or whatever… The all important soil testing should be paramount in garnering a more answers.

I am untutored if England recognizes the UNESCO cut-off-date as they have established laws of their own national laws to safeguard historic materials.

The more I think about this tale of: ‘The wreath was my Grandfather’s,’ it reads like someone has been watching too many Indiana Jones movies!

Absolutely stunning! Thank you for the photos. They made my day.

Okay, time has moved on ‘n tiz 5 yrs later and welcome to Covid.

Does anyone know if there is an update/follow up about the piece and any other information about it?

Please…