Just in time for Memorial Day, the National Park Service has discovered extensive looting of the Petersburg National Battlefield in Virginia. Rangers found a large number of pits dug by treasure hunters looking to steal Civil War artifacts. They likely used metal detectors to discover small, easily removed and carried objects like uniform buttons, buckles and bullets.

Just in time for Memorial Day, the National Park Service has discovered extensive looting of the Petersburg National Battlefield in Virginia. Rangers found a large number of pits dug by treasure hunters looking to steal Civil War artifacts. They likely used metal detectors to discover small, easily removed and carried objects like uniform buttons, buckles and bullets.

These excavation pits were discovered by park staff last week. That area has now been sealed off as an active crime scene while the rest of the park remains open to visitors who, unlike the looters, have respect for thousands of Union and Confederate troops who were killed and wounded in the Siege of Petersburg.

Since the park is nestled in an urban setting, Rogers said, “Someone may have seen something we need to know. The public can help by calling in any tips or other information. The toll-free number is 888-653-0009 and callers can leave a message.”

The looting at Petersburg National Battlefield is a federal crime covered by the Archeological Resources Protection Act of 1979. Violators, upon conviction, can be fined up to $20,000.00 or imprisoned for two years, or both.

Unfortunately it will be difficult to recover any looted artifacts. The kinds of things likely to have been found would be next to impossible to trace specifically to the Petersburg battlefield as opposed to the Civil War period in general.

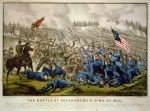

Petersburg is where the battles that finally ended the Civil War took place, and much like the war itself, it took far longer and claimed more casualties than anyone expected. The longest siege in US history began in June of 1864 after General Ulysses S. Grant put a stop to six weeks of failed frontal assaults on Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army defending Richmond and withdrew to Petersburg. Then the second largest city in Virginia, Petersburg was a railroad hub and an essential supply line to Richmond.

Petersburg is where the battles that finally ended the Civil War took place, and much like the war itself, it took far longer and claimed more casualties than anyone expected. The longest siege in US history began in June of 1864 after General Ulysses S. Grant put a stop to six weeks of failed frontal assaults on Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army defending Richmond and withdrew to Petersburg. Then the second largest city in Virginia, Petersburg was a railroad hub and an essential supply line to Richmond.

The Union army failed to take Petersburg thanks to its leaders’ usual lack of coordination and failure to immediately press hard-won advantages, so they settled in for the long haul, digging trenches that would ultimately cover 30 miles of ground from the outskirts of Richmond to the outskirts of Petersburg. The subsequent siege lasted nine and a half months and saw a dozen major engagements between the Union and Confederate armies. With soldiers digging ever-growing networks of trenches, long periods of inaction peppered with battles that achieved few tactical goals at a great cost of human life, Petersburg presaged the approach that would characterize the First World War.

The Union army failed to take Petersburg thanks to its leaders’ usual lack of coordination and failure to immediately press hard-won advantages, so they settled in for the long haul, digging trenches that would ultimately cover 30 miles of ground from the outskirts of Richmond to the outskirts of Petersburg. The subsequent siege lasted nine and a half months and saw a dozen major engagements between the Union and Confederate armies. With soldiers digging ever-growing networks of trenches, long periods of inaction peppered with battles that achieved few tactical goals at a great cost of human life, Petersburg presaged the approach that would characterize the First World War.

The Third Battle of Petersburg on April 2, 1865, was the last battle of the siege. The Union victory forced General Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The city of Richmond surrendered on April 3rd. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, mortally wounded by exhaustion, disease, hunger and desertion, fought on for another week until it was defeated at the Battle of Appomattox Court House and Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant on April 9th, 1865. That triggered the surrender of the rest of the surviving Confederate forces and the end of the American Civil War.

The Third Battle of Petersburg on April 2, 1865, was the last battle of the siege. The Union victory forced General Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The city of Richmond surrendered on April 3rd. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, mortally wounded by exhaustion, disease, hunger and desertion, fought on for another week until it was defeated at the Battle of Appomattox Court House and Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant on April 9th, 1865. That triggered the surrender of the rest of the surviving Confederate forces and the end of the American Civil War.

(fill in swear words of your choice here) <-me Geez, I hate people who do that!

It’s a pity the US Park Service did not initiate proper battlefield studies and clearances using metal detectors decades ago. They could even have used volunteer detectorists to do the work, with some sort of reward scheme for their finds. The information that can be gained about the course of battles from such material is often unique and of great value. The Little Bighorn battlefield studies are a perfect example of this. I’d suggest eBay be asked to ban the sale of dug civil war relics, but these people sell their loot at antique shows, flea markets, gunshows, craigslist etc. etc. Pretty hard to stop, but if the materials were already collected there’d be nothing for them to loot.

Some people are just disgusting.

Looting is a big business. TV shows have convinced people that artifacts are valuable collectibles.

Last week the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian hosted a press conference online to protest the sale of Native American human remains and artifacts at EVE auction house in Paris. Representatives from the tribes and the federal government outlined their thwarted efforts to regain their sacred items.

Completely agree with Rob, above.

The park Service refuses to sweep for, recover and preserve artifacts, preferring to leave them to rot in place. That would’ve prevented this.

This attracts two types of hunters; the fellows who are just looking for what’s marketable, and the ones who feel it’s much more respectful of the past to recover artifacts to carefully preserve in collections than to let them decay on site. They’ll tell you this is a noble calling. The two groups loathe each other, but many of the first sort lately lip pious platitudes like the second.

A battlefield is a grave site. Respectful treatment prevents extensive excavation of such sites. The notion that artifacts are “rotting” in the ground makes little sense to me. All archaeology is inherently destructive. You destroy its context in order to retrieve an artifact, and if it happens to be organic material, you accelerate its “rotting” exponentially by digging it up. So it seems to me there ought to be a reason beyond the mere acquisition of the artifact itself to justify the destruction, all the more so when there are human remains from just 150 years ago in the context.

That’s not to say there isn’t a place for metal detector hobbyists to aid in archaeological research. There have been several extremely successful collaborations — see the excavation of Camp Lawton, for example, or the discovery of the Omø hoard — but just because you have a machine that can alert you to the presence of metal doesn’t mean you can excavate a site with proper care for what the context can teach us. That’s all the more significant nowadays when it’s possible to discover an enormous amount from trace materials in soil. The artifact is not necessarily the most important piece of the puzzle. It’s just the easiest to recognize.